Favorite Bookish Thing 2016: Lines by Hesiod

This essay was first published in SHARKPACK Poetry Review! This piece is republished with permission. See the original here: https://sharkpackpoetry.com/2016/12/26/favorite-bookish-thing-2016-lines-by-hesiod/

In a state of near-misery, I return to reading I did this summer: Dorothea Schmidt Wender’s ’73 translation of Hesiod and Theognis, included in the Penguin Classics series. Hesiod is most exciting, for me, in Works and Days, and especially in the verses concerning the ages of man. A famous passage (lines 170-201) concerns our own age, that of iron. Hesiod cries out:

I wish I were not of this race, that I

Had died before, or had not yet been born.

This is the race of iron. Now, by day,

Men work and grieve unceasingly; by night

They waste away and die.

The thumping iambs suit the content. Casting the poem in blank verse insists this is an English poetry made of its Greek original, a sure method for frustrating purists and exciting a sometimes-reticent reading public. The first line quoted intensely foregrounds the poetic subject—’I wish I [. . .] that I,”—and seems somehow to heighten the friction between the subjunctive mood and the lamentation. The heat produced seems angry to me, frustrated, incensed at being alive in the age of iron. Compare Wender’s lines, anyway, with the same in a more recent translation by Daryl Hine:

How I would wish to have never been one of this fifth generation!

Whether I’d died in the past or came to be born in the future.

I have not read that translation, but expect that these are intended to simulate the dactylic hexameter of the ancient Greek. That approach might work for some ears, but there’s something pleasing in the comparative austerity of Wender’s lines:

The just, the good, the man who keeps his word

Will be despised, but men will praise the bad

And insolent. Might will be Right, and shame

Will cease to be. Men will do injury

To better men by speaking crooked words

And adding lying oaths; and everywhere

Harsh-voiced and sullen-faced and loving harm,

Envy will walk along with wretched men.

Perhaps I’m shoehorning a particular politics into the way the line breaks operate to isolate ideas, but it hardly seems circumstantial that ‘Might will be Right’ appears on the same line with ‘insolence’ and ‘shame,’ especially in a passage lamenting the fallen state of humankind. And there may be some importation of biblical language going on—envy walks beside the wretched, rather than we wretched being led beside the still waters—which would be disappointing if the replication of the living, breathing Hesiod were the goal.

Instead, we get the Hesiod we deserve by these importations and modifications. It speaks to the nature of great poetry that even Hesiod’s widely reported misogyny serves in our current moment. The poet says, ‘Men will destroy the towns of other men’: and the way that the destruction of the town is bookended by ‘men’ reminds me—or (woe to the republic) forewarns me—of the costs to us the impending period of masculine overdrive will impose.

As we approach the inauguration, let us overhear again Hesiod’s song to his brother:

I say important things for you to hear,

O foolish Perses: Badness can be caught

In great abundance, easily; the road

To her is level, and she lives near by.

About d. eric parkison: Poet, teacher, book peddler. Part-time misanthrope, full time guilt sufferer. Porch grump in training.

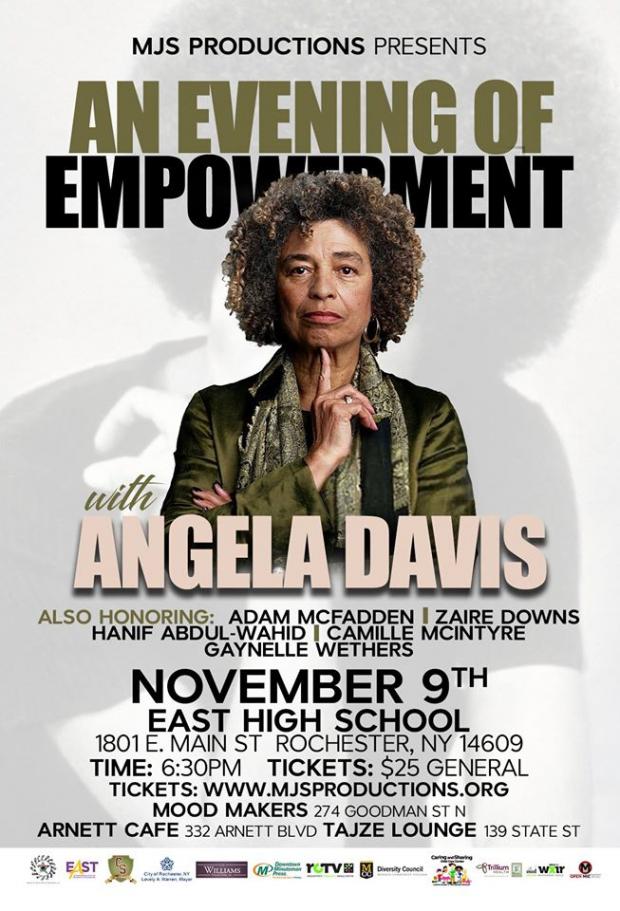

An Evening of Empowerment with Angela Davis

Author, activist and scholar Angela Davis spoke at East High in Rochester, NY, the day after the fated election of Donald Trump. Her talk ranged in topic: mass incarceration, the Black Lives Matter movement, the Standing Rock Sioux pipeline protests, and the need to build a third political party. You can view the entire speech at this link: https://vimeo.com/192179582

Protest of Rochester School Board President Van Henri White

Sitting it Out at Standing Rock

Driving from that dusty rhinestone, Las Vegas, across northern Nevada, Arizona, Wyoming, and into South Dakota on I-15N requires patience and serenity rare for me and completely alien to my companion. Our trip to Standing Rock on that dull highway took us through the most featureless, colorless lands in this country. Flat as old Coke. In our boredom, we even found ourselves intrigued by the odd snow fences in Wyoming and thrilled to see a hillock or a tiny gorge. Now and again there’d be an outcropping, towering over the bland landscape like a medieval castle, but for miles we had only sagebrush and an occasional steer as companions. In 1300 miles we’d seen no wildlife, few birds, not even road kill. The dead land had been stripped by cattlemen to smooth sterility. Houses were miles from one another. Gas stations so far apart the car was often running on our nervous breaths as we finally found a small pump in a cowboy town. No motels: we slept in the car at a truck pullout. We were excited to finally make the turn onto Route 83, a back road leading us to the smallest Standing Rock encampment where our arrival was awaited. We’d heard earlier that evening that road was a safe approach among increasingly patrolled entrances, and was about a hundred miles from our goal. We were buoyant. Even my friend’s elderly service dog woke, sniffing and nudging, sensing our excitement.

It was dark as dirt as we moved along Route 83, cautious as we’d been the entire trip to observe the speed limit. Suddenly, red and blue lights slashed through our cheer and an unctuous, tubby sheriff tapped on the passenger-side window claiming we’d been speeding and demanding ID from us both. The weeks-long nightmare began.

––––––––––

Ellen sits at the desk of the dog-friendly motel in an isolated town at the northern edge of South Dakota, population 714. She manages the motel twenty-four hours every single day, year round, virtually imprisoned by the job, as she cares for her disabled adult son. More, she is isolated in this hunting, hating town because of her humane and inclusive values – a silent outcast. Her joy the first night I appeared, speaking of Standing Rock, lit up her weary face. By the next day, we’d had a rousing discussion of the encampment, treaty rights, regional police, and the constant racism she’d discovered since her move from Dallas, nauseating cruelty. (She’d seen police drive into her parking lot, smash a young Native American woman’s car windows and strew her possessions for no cause but hatred.) From that moment, her affection and generosity made this dusty town bearable. And I know she was grateful, relieved for connection. Why, you ask, was I in a motel lobby in the middle of the night with someone else’s dog?

––––––––––

After the stop and the shuffling of our ID cards, the sheriff called us out of the car and swiftly separated us. We were too flustered and the demands too rapid-fire for us to quickly claim our rights to prevent search and seizure. We were also nervous to see he had an agitated dog in the truck and were keenly aware of our utter isolation. My travel pal, Layla, was hustled into the sheriff’s vehicle, leaving me outside with the very flummoxed assistant cop (who acknowledged he’d never worked with this sheriff and didn’t know what the hell was going on.) As Sheriff Varilek (we learned his name later) began to talk with her, he slyly turned the dash cam off. Layla was coerced into permitting a search of her vehicle, told she’d either allow the search or we’d both be arrested on invented charges, the car impounded, the dog sent to the local animal shelter with no guarantee of retrieving her. In this dark, unknown territory, threatened privately and still holding to hope any invented charges wouldn’t amount to much, she consented. At no point was she told of her right to refuse. We were both anxious to get her dog out of the car and away from weapons, fearful she’d be harmed, while the smug, heavily armed sheriff began investigating our possessions. Not wanting surprises, Layla answered his question honestly: yes, there were medications in the car, some of them controlled substances with prescription documentation (hers and mine), among them prescribed, precisely formulated, fully licensed medication to treat her auto-immune disorder, perfectly legal in her home state. And perfectly illegal, we learned, in the backwater state of South Dakota. (Two days later, North Dakota, just an hour away from the spot where we were stopped, voted in a compassionate use law for this very formulation, a bitter joke.) The car was tossed end to end and Layla was arrested.

She’d been told in the car that they’d been waiting for us. They knew who we were, what route we’d been taking, when to expect us, where we were headed. They knew our backgrounds. They’d heard our conversations. And they did not want us at camp. We knew then our phones had been hacked and I remembered camp complaints of surveillance and communications jams. And, too late, I recalled that Stingray surveillance devices had just been issued to the militarized police, militia, and mercenaries assaulting Standing Rock. This technology was used at the camp to thwart communication, scramble text and video messages, steal funds from PayPal and fundraising accounts, track incoming goods and torment those trying to stay in contact with home, medics, and those bringing in supplies. The Stingrays (and other brands of surveillance devices) have been brought in and employed by TigerSwan, the black ops that Blackwater morphed into after its horrific misdeeds in Iraq were exposed. They've provided and supervised the use of the most militarized weapons used against Water Protectors, including water cannons, LRAD noise cannons, tear gas, ammunition and the concussion grenades that blinded one woman and tore the arm off another. They also run surveillance planes over the camp day and night both for intimidation and observation, much of it using infrared cameras to track the number in each tent. They fly in the dark without lights to confuse campers and disrupt sleep. Federal generosity with wartime equipment apparently also reached to the camp’s outskirts, arming local officials with all they needed to stop would-be Water Protectors. Together they could read our very thoughts.

As they began to drive away, I realized that my friend had our active GPS and I had no notion where they were taking her. The sheriff told me to go up the road to a distant turn-around and follow them. When I did as he demanded, he’d already sped off. The road was dark. I gunned the engine and headed back the way we’d come, guessing which way he’d gone. It took a long while at 80 mph to find them. We sped at that pace through dark country, over a bumpy bridge spanning the Missouri, through a small town, and on another twenty miles to the jail. (Remember that we were pulled over on a phony speeding charge.) Seven counties surround the Standing Rock encampment and the jails in every one of them were full, stuffed with people nabbed from or around the camps on false or exaggerated charges. The procedure in all of the arrests was to make accusations that would threaten long sentences. Those arrested endured all the notorious humiliations publicized after the arrests of many journalists, photographers, filmakers and other notables (including Amy Goodman of Democracy Now and Deia Schlosberg, filmmaker of the Gasland movies, and the many jailed Water Protectors.) I got out of the car and ran to the door of the Quonset hut county jail just as it was slammed in my face. There was no other entrance. I stood in dark and silence.

The bumbling assistant sheriff finally emerged, looking over his shoulder, with a phone number scribbled on a tiny scrap of paper. ‘Call here and you can see her in twelve hours,’ he whispered. And then darted back in. I was flummoxed and furious. Remembering the frightened dog, I went to the car to assure her all would be well. Would it? I wished someone would scruffle my fur and make false promises.

That’s when I met Ellen.

––––––––––

After hearing my story, Ellen offered a room at a reduced rate, ignoring that I had a big, lumbering old hound with me. I wrestled my daypack from the mad upheaval in the car, examined the small, clean, shabby room, settled Ruby into her bed, and dropped into mine. This would not be a night of sleep.

In the morning I called at the twelve-hour mark. No go. I called later as instructed. Nope. I couldn’t leave a message. Later I could, but without any assurance it would be delivered. Meanwhile I’d searched for a bondsman and found the only one in the seven counties, a hundred and fifty miles away We made arrangements to meet at the jail. Finally, through plexi, with an ancient phone, my friend and I spoke briefly, a doughy guard behind her monitoring the conversation, before the bondsman arrived. Not knowing yet of her evil treatment, I was alarmed at her deflation from fierce to bedraggled. Bail was preposterously high, but I’d scrambled to have the bond fee in hand and was able to pull my bud out of the pit. We headed to Ellen’s motel, our room tucked between hunters and their kill.

––––––––––

It was clear the police both inside and outside the encampment were illegally monitoring cell phones. There are countless tales of strange cell phone behavior, battery depletion, communication cut-off, dead phones, broken calls and text. In our case, I presume the officer, since he boasted he knew everything about us, was using a portable device in his car to thwart all entries from the south. Later I heard him in the courthouse telling a covey of cops that he pulled everyone over on the charge of carrying marijuana. He lowered his voice to describe his techniques. He or his colleague sniffed the car, one saying he smelled dope, they pulled out the dog, and whether it had been there before or not, it was found in the search. I learned later he was known as a disreputable cop and this was his fourth job in the last few years. Public defenders often pleaded overload to avoid taking on his cases.

Medical marijuana is currently legal in 29 states, including my own state of NY, ushered in under compassionate care laws, Recent elections will shortly expand that number by 4. The number of disorders, and the doctors assigned to prescribe it, are both limited in most states. Those, too, will shortly expand. While there is still debate about its efficacy, and trials have been small, don’t include placebo tests, and do not meet the protocols for scientific testing, much anecdotal evidence indicates it is useful. It is generally assumed that the reported benefits merit further testing and there are few concerns about its present use. Drowsiness and long-term cognitive slowing are the major concerns.

Edward Snowden has long been my hero. He risked everything to reveal the extent of governmental spying, using invasive technology to break into our computers, our phones, our private conversations, our business arrangements. We know that the meeting places for activist groups and our bookstores are infested with listening devices. Even when we have identified encrypted apps to communicate with one another, Stingrays and their ilk can break those barriers quickly. Since the infuriating technical and tactical invasion of the camp and supporters, confounding communication and gathering ‘evidence,’ I’ve become obsessed with reading about illegal surveillance. Here are just a few articles with information about the invasive governmental and private corporate capacity to own us. At the very least, our computers and phones must be encrypted in these perilous times.

I don’t yet know how to do that. Long a Blackberry user, which was designed with sophisticated encryption built into the device, I was complacent after I made the change to iPhone. Despite dire articles detailing the betrayals of privacy by Apple, AT&T, Verizon, assorted apps and other apparatus and service providers, I didn’t really expect such significant personal effect.

Psychological and Cyber Warfare at Standing Rock

Protestors at Standing Rock subject to 24-hour police surveillance

FCC Investigates Stingray Spies While DAPL Works in Secret at Standing Rock

Stingrays: A Secret Catalogue of Government Gear for Spying on Your Cellphone

––––––––––

While we waited, we discovered the tenor of the towns around us. With no preconceptions, I made my jaunty way into a café, ready to chat with any willing stranger. Customer suspicion and discomfort rose like dust around us. We didn’t look like hunters. We didn’t look like locals. We looked like strangers on their way to stop work on a pipeline that fed their families. Their mocking voices rose, full of racial epithets, full of spit, full of hate. Everywhere we went, except for Ellen’s office, we heard loud voices, not shouting precisely at us but at the air around us, decrying ethnic groups and lauding Trump. It was lonely and unnerving. I understood, then, the isolation of the Water Protectors in a land that still despised Native Americans, seized their land, desecrated their sacred places, demeaned their culture and language, mocked their rituals, discounted their very humanness. How was it that I was not in camp, aiding their defense, but stuck instead among the likely masked mercenaries attacking them?

Setting out for the first court hearing, we were astonished to find the courthouse was one hundred twenty five miles away. The first appearance was simply a reading of the accusation, a listing of the charges, and assessing the probable penalty – hardly worth the gas. We expected a high level misdemeanor with a substantial penalty. When the charges comprised one felony and two serious misdemeanors, with a likely sentence of eight years in prison, we paled, heads spinning. Layla kept her composure as she was granted the right to a court-appointed attorney and given a date for arraignment. Still unused to the distances and stretches of time in this sluggish state, we could barely fathom that the attorney was more than two hundred miles from the courthouse (well over three hundred miles from our motel) and she wouldn’t have an opening to meet us for an entire week. In that time we began to search for other legal support from the many organizations supporting Water Protectors, but they were already triaging camp cases and unprepared to take on even worthy cases of those still on the road. We were warned, though, not to bring in a too-confident, shiny-suited attorney from the big city. That would only harm our case with the parochial judges. We should look for a local legal eagle. Trouble was, the only nearby lawyer’s office had four walls full of trophy animal heads, an unlikely match for us, activists against wildlife extinction. We waited the week.

We were constantly monitoring events at the encampments and were – like all activists in the nation – riveted and horrified by the violent assault on Water Protectors on November 20. It nearly drove us mad, being so close and unable to help. I needed strength for organizing legal needs, caring for the dog, maintaining composure in the surly surroundings and did not give way to despair, expecting to swim in it when I returned home. (That expectation was fully met.) With mounting expenses and plummeting spirits, we were relieved to receive financial and emotional support from my friends and some legal guidance from her pals and mine. Her court date scheduled two weeks hence, we prayed that the legal ruffians would settle for a commitment to clear out of the state. They’d already made examples of us. I could hardly bear that the energy, time and money I’d spent to be part of this monumental movement had been vaporized. My thwarted desire to play even a small part in this resistance to genocide and ecocide was burning a hole in my heart.

––––––––––

The arraignment was perfunctory, the trial set for yet another week later. A long week it was, full of cheese sandwiches (no vegetarian meals in this beefy town) and weak coffee. The attorney, at first certain she could get all charges dropped, had to negotiate a sterner sentence. In the end all charges were reduced to misdemeanors, two requiring fines of $500 each and the last remaining on record to be expunged in two years if there were no further arrests, even for a traffic violation.

Another South Dakota shock: use of a public defender is not free. In an article titled, A Mockery of Justice for the Poor, John Pfaff, writing in the New York Times notes, “The situation in South Dakota highlights the insanity of this. South Dakota charges a defendant $92 an hour “for his public defender, owed no matter what the outcome of the case. If a public defender spends 10 hours proving her client is innocent, the defender still owes the lawyer $920, even though he committed no crime and his arrest was a mistake.” With just such a fee, total court expenses were $1600.

Payment arranged, we fled from the courthouse to the nearest town in Wyoming with a pet-friendly motel. I drove. I was so grateful for the healing of sheer beauty as we wound our way to Vegas on roads slicing through Wyoming’s Granite, Ferris, Shirley, Medicine Bow and Sierra Madre mountains, and through Utah and Arizona’s stunning red canyons.

There was one last thing though. Google Maps had been loyal throughout our trials, leading us on digital leashes from one place to another. But before we left oil country, things got a little weird. Since we barely had a signal through all the mountain ranges, we’d take screen shots of the maps and directions as we could and follow those. When we could, we’d follow voice directions. We noticed that Siri was sending us down new roads, not the ones we’d saved, but we twisted and turned and trusted we were headed in the right direction. After we were directed further and further from our goal, taken right to the door of three oil refineries, one after the other, miles apart, we contacted Verizon via a direct line system my pal had installed. Sure enough, we’d been misled for miles, the refineries far off our path. Within moments Verizon restored the maps. I’m still wondering if this was one last invasive digital joke. Only Edward Snowden knows for sure.

Also by Katherine Denison: A Jury of One's Fears | What happened today when I went in to deal with the ticket from the Pink Ruler Boys and why it was further proof of corruption

Related: Locals Rally in Solidarity with ND Sioux | Local author discusses story of family murders by KKK cops in Arkansas | NYS is a no SWAT zone! Reject SWAT conferences & police militarization

From Burning Pride Flags to a Neighborhood Rally

see the original piece here: http://transgenderuniverse.com/2016/11/17/from-burning-pride-flags-to-a-neighborhood-rally/ Kameron gave us permission to cross-post to Rochester Indymedia! Thanks Kameron!

The morning after the election, I woke up to a text from a friend who said, “Hi! We’d like to get a rainbow flag to hang at the house in solidarity after what happened yesterday. Do you know where we could purchase one?” When he had said, “what happened yesterday,” I figured he meant Trump, but once I got on facebook, I saw that two pride flags had been burned in my neighborhood the evening before. Talk about getting hit close to home! It is being investigated as both arson and a hate crime, but so far there are no suspects.

So I looked up information for the gay pride store that had been a mainstay in our city, first opening in 1989 as a leather and fetish supplier, and later changing ownership a couple of times and morphing into a place that had something for everyone in the LGBTQ+ community. I was shocked and saddened to learn that it had closed in August with the death of the current owner. So instead I recommended a couple of novelty stores to my friend, hoping he’d be able to track one down.

“As the events unfolded, it became apparent that there was nowhere, locally, to get a pride flag because every place had sold out!”

As the events had unfolded, it became apparent that there was nowhere, locally, to get a pride flag because every place had sold out! A fellow neighbor had ordered 120 more flags, and she was formulating a plan to get these out to people and acquire more, flooding the area with rainbows.

On Friday evening, another friend in the neighborhood had texted me to see whether my spouse and I were going to the rally in the morning (I feel fortunate that I have so many friends who are in the loop, because there are times when I am totally living under a rock!). I said, “Yes,” as if I knew all about it (ha ha), and we made a plan to go together.

And so, my spouse and friends (a queer couple with a 10 year-old son) and I walked over to a nearby park Saturday morning, carrying signs and wearing fun outfits. As we approached, I felt a wave of emotion, moved by the size of the gathering, the amount of rainbows flying in the air, and the openness of everyone there.

Mary Moore, the organizer and the neighbor that ordered the flags, stood up on a table to announce the intentions of this rally: to hand out more flags for community members to show solidarity, and to show LGBTQ+ members in this neighborhood how much support is out there. Mission accomplished, by leaps and bounds! There were so many allies and families, along with people who identify as LGBTQ+. I walked around the outskirts of the crowd, taking photos and scoping out all that was happening. There was a station for people to make rainbows out of ribbons, as well as a spot to make construction-paper rainbows. Someone was doing face painting, and there was also a place to sign up to order a flag, because the 120 that Mary had ordered for the rally had sold out in 9 minutes!

The director of the local gay alliance also stopped by, got up on the table, and delivered a similar message of hope and love. I started to feel more comfortable, and moving into the crowd and approaching people with signs, asking whether I could take their photograph. I saw a couple of acquaintances, and where I would normally be too shy to strike up a conversation, in this environment, I went right up to them to say hey and chat for a while. My spouse and friends also connected with neighbors we know, as well as meeting a few new people.

I posted a photo album of the event on Facebook and watched my social network do its work, spider-webbing outwards from friends I had tagged, to friends of friends and beyond. I also messaged Mary, the organizer, to thank her and to ask her a couple of questions.

“…I learned that she has been an ally and supporter of LGBTQ+ rights for a long time.”

We talked on the phone for a bit this morning, and I learned that she has been an ally and supporter of LGBTQ+ rights for a long time, even doing advocacy work in Washington DC. She said that for the past 8 years though, she could ease up because there was someone in the White House who was pushing for the same things; she could focus on her career, working as a lawyer in private practice, and on her family.

She first heard about the 2 flag burning incidents from a friend, while picking her kids up from daycare. Her husband had heard about it through the website, nextdoor.com, which acts as a community bulletin board and a way to connect with others nearby. I just joined, myself, to see what it’s all about (and to try not living under a rock quite so much). Sure enough, 5 days ago, there was a post from one of the victims of the hate crime, stating, “I hang a rainbow flag on my front porch and someone burned it down. Thankfully my house didn’t catch fire. The [police are] currently investigating; please keep an eye out for suspicious behavior in the area.”

And then, as a response, Mary Moore created the event, “Let’s Gather to Support Our Community.” She wrote:

In response to the burning of two rainbow flags in [our] area, let’s stand together and show that our community is tolerant and welcoming, regardless of who you love, where you worship, where you were born, your political affiliation, the color of your skin, or how much money you have. Many people in [our] neighborhood have been buying rainbow flags to put out in solidarity and to give to friends. … Would people be interested in organizing a central meeting place this weekend or next to give out flags and just to stand with our community in solidarity? … Please comment below if you would be interested in a gathering like this, if you have or can buy flags to distribute, and/or if you can assist with finding a location for this gathering. If there is interest, then we can set up a formal event on here.

I know that this is just one of many issues and injustices within our communities and that we are all so very busy, but we have to start somewhere and do what we can with what we’ve got every day. Let’s not be bullied or let our neighbors be bullied.

It all came together from there. I want to personally thank Mary Moore for showing my friends, my spouse, me, and everyone else who could be there for how much we are supported by our neighbors!

Regarding our rainbow flag status: We don’t have one, but when we moved into our house ten years ago, we dubbed it the “Rainbow Ranch,” and I spray painted a rainbow on our garage door. I sure as hell hope that never gets burned down – we just put a new roof on it a couple years ago!

Related: Final Presidential Debate | New App: LGBTQ+ health care info & reviews!

About Kameron: Kameron is a genderqueer janitor, radio DJ, and blog writer. He lives with his spouse and two cats in a house. He is in the midst of his own version of a non-binary transition, and he loves to talk about it! Feel free to reach out about that or anything else, really.

An interview with actress Hana Chamoun from 3000 Nights

Hana Chamoun, a talented Lebanese-Palestinian actress, was in Rochester on September 18, 2016 to talk about 3000 Nights after it screened. Moderating the discussion was Linc Spaulding from Witness Palestine Rochester. This heart-rending and amazing feature film opened the Witness Palestine Film Series at The Little Theatre.

The Toronto Palestine Film Festival described 3000 Nights this way:

Layal, a young newlywed Palestinian schoolteacher is arrested after being falsely accused and sentenced to 8 years of prison. She is transferred to a high security Israeli women’s prison where she encounters a terrifying world in which Palestinian political prisoners are incarcerated with Israeli criminal inmates. When she discovers she is pregnant, the prison director pressures her to abort the baby and spy on the Palestinian inmates. However, resilient and still in chains, she gives birth to a baby boy. Through her struggle to raise her son behind bars, and her relationship with the other prisoners, she manages to find a sense of hope and a meaning to her life. Prison conditions deteriorate and the Palestinian prisoners decide to strike. The prison director warns her against joining the rebellion and threatens to take her son away. In a moment of truth, Layal is forced to make a choice that will forever change her life.

Watch the trailer below:

Rochester Indymedia journalist T. Forsyth had the chance to meet Hana and was able to send her some questions via email that she happily agreed to answer.

1) Does the math work? Is 8 years actually 3000 Nights?

Yes.

2) How did you get involved in acting? And this specific film project?

I was 5 years old when I acted in my Father’s film In The Shadows of the City (2000), and ever since then I knew I wanted to be an actress. I directed and acted in several short films and plays throughout my adult life. I was involved in this film project from the very beginning when my mother started working on it. She created a character just for me, but I still had to audition for the part.

3) Your mother directed the film and at the panel discussion I believe you said you were her personal aid. With regards to the film, what were your tasks? And what kinds of hurdles did you have to overcome in making the film?

I took a semester off from university in January 2014 and moved to Amman, Jordan with my mother where we started the casting and preproduction processes. I was my mother’s shadow for 6 months, learning everything I could from her and being involved in the creative process. One of the biggest obstacles we encountered was working with a two year old child, and one of my responsibilities was to keep him happy and ready for the shoot. Asking a two year old to memorize lines or deliver a performance when its needed, is a very difficult task.

4) Can you give me some history (and the location) of the prison used as the backdrop for the film in Jordan? What was the reaction of the Jordanian government when you went to make the film, if any? What about the locals? Did you hear anything in particular, stories, fragments, etc., about what happened in the prison you were shooting?

The location where we shot the film was in an abandoned military prison in Zarqa, Jordan. We had the cooperation of the Royal Film Commission and with their help we were able to get a special permit from the Jordanian army to film in the prison. We were lucky to be able to shoot the whole film in the prion and use it as our base.

5) What was your reaction to the prison on your first tour of it? How did the other cast members react?

Seeing the location for the first time was both moving and chilling. Since it was a real prison we could still see tallies and arabic writing carved into the walls by the former prisoners. There was a haunting atmosphere in that abandoned prison that gave a wonderful mood to the film. One of the actresses, got very emotional when she first arrived on set because she remembered her brother who was imprisoned for several years in an Israeli prison. She recounted to us the traumatic experiences she went through as a child visiting her brother in the prison. She is a Palestinian actress who played the role of Ze’eva, an Israeli inmate. After the shoot was over she shared that playing an opposing role from her reality was therapeutic.

6) Mara raised a great connection that the prison is a metaphor for the occupation. Was that intentionally built into the script? If so, could you tell me more about the connections between the occupation and the prison environment in general?

The oppressive prison system parallels the brutal occupation that dictates the lives of the Palestinian people on a daily basis. Gaza is a huge open air prison because of the blockade enforced on it, and the West Bank is under occupation with military checkpoints, settlements and an Apartheid wall confining people and limiting their freedom of movement. Families and loved ones are separated from each other and denied the resources of their land. Human rights violations such as forced evictions, demolition of homes, unwarranted arrests and torture are far too common. The mass incarceration technique has been used as a means to weaken and silence resistance, resulting in the imprisonment of over 1 million Palestinians over the years.

7) Last year's Witness Palestine Film Fest had the theme of connecting the dots, from Ferguson to Palestine. What connections do you see in the film? What stands out?

I can see a lot of connections between the Black struggle against police brutality in the US and the Palestinian struggle against the Israeli Occupation. The same oppression techniques (which can be seen in the film) are used by the US police force and the Israeli military against their respective civilian population, including shooting of unarmed protesters, indiscriminate beating and use of tear gas. This connection is directly linked to the training of US police officers by IDF soldiers in Israel.

8) Watching the film I had an incredible emotional reaction. As an actor, watching yourself in Rochester on the big screen, I was curious what you felt and does your impression of the film change? If so, how?

Every time I see the film on the big screen I feel like I am watching it for the first time, crying and laughing with the audience. But I also remember the funny, frustrating and difficult moments the cast an crew went through while shooting the scenes. I always tear up in the scene where my sister dies in the film (I’m not sure if it’s because I give a truthful performance or because I remember how hard it was experiencing that - I think it’s a combination of both).

9) How has the film been received by Jewish audiences in Europe, America, and Israel?

The film has had a positive reception by audiences all over the world. It has created discussions among everyone and been an eye opener for some Israelis who are sheltered from or chose to ignore this reality.

10) At the panel discussion you spoke about the relationships between cast and crew. How did folks nurture those connections after acting out such violent and ugly scenes? Did everyone participate in any rituals together?

My mother comes from a documentary background so she is not used to interfering with the performance. She relies on capturing the truth of the moment and the true essence of characters she films, so she gave us a lot of freedom to explore and improvise on set. We were able to do that successfully and create beautiful spontaneous moments because we built strong relationships in the rehearsal period two weeks prior to the shoot.

11) How did you decompress at the end of a shoot?

I definitely experience PPD (post production depression) after the shoot was over. I missed everyone I worked with, but more importantly I missed having such an active role in the creative processes of the work. I felt all along as though the film was my baby and having to depart from the people, location and routine was sad. Working on the film was a very fulfilling and life changing experience for me.

12) (spoiler alert) You also mentioned you had no professional acting experience before the film. Your character's reaction to seeing her sister shot and killed was chilling and felt raw and authentic. How do you think that scene would have played out had you been professionally trained? (Personally, I thought you were fucking amazing. Chills.)

I think even if I had acting training before the film I still would have done the scene the same way. The way I act hasn't changed since I began training, the only difference is that now I am more aware of myself and the process I have to go through to prepare for a role. Acting for me is, and has always been, about believing in and living through the circumstances of the film/play. When I can’t truthfully do that then I can’t truthfully act.

13) Last question. Audience members referenced a certain feminist quality in the characters and their decisions throughout the film. How do you define feminism? Is that a word you identify with? How is your feminism different from, say, American, white, liberal feminism? Or your mother's feminism, for that matter?

Feminism to me is when women can stand up against oppression, subjugation, and in solidarity with other struggles for equality. In this film the women’s struggles are against the oppressive prison system and the injustice of the occupation. Another important struggle and strong feminist message in the film, is motherhood and how the protagonist, Layal, has to deal with that in the context of the prison.

14) Bonus question(s): I know the script was based on true stories from women inside of these prisons. I'm not sure if you know, but was the portrayal of the prison a portrayal of the absolute worst prison or just your average prison at that time? Have you heard of audience members writing the film off as being too harsh or too radical a portrayal of prisons at that time? Or, instead of being written off, has the film brought a kind of reckoning with a reality many perhaps refused to acknowledge or were ignorant of?

The prison experience portrayed in this film is an average one compared to other experiences. There are some elements that my mother chose not to put in the film for various reasons, for example the extreme and brutal torture techniques that were used on the women, especially the rape of the women by Israeli soldiers, which was very common.

Thank you so much!

Related: Miko Peled interview by Witness Palestine Rochester | What Islam means to the White Male- Through the lens of a Bullet Covered in Bacon Grease | After the Requiem, Chomsky answers questions | The Apocalypse’s Apocalypse and Post-Apocalyptic Visions of Sunshine and Blessings | Rev. Hagler's U of R speech and an interview with student organizer Hijazi | Rochester Rally for Palestine | From Ferguson to Palestine to Rochester: the truth perseveres! Rev. Hagler speaks! | New venue found for Palestinian rights speaker after divinity school rescinds invite

Final Presidential Debate

Miko Peled interview by Witness Palestine Rochester

Acclaimed Israeli writer and activist Miko Peled kicked off the fifth Witness Palestine Film Festival on Sept 15, 2016. He spoke about "Justice and Freedom: the Keys to Peace in Palestine" at the Historic German House, in Rochester, NY. The event was co-sponsored by the Rochester Chapter of Jewish Voice for Peace.

Miko Peled has written "The General’s Son: Journey of an Israeli in Palestine" and he has traveled extensively, giving talks across the US, the UK, Canada, Australia, Germany and Switzerland. More information at www.WitnessPalestineRochester.org

Related: What Islam means to the White Male- Through the lens of a Bullet Covered in Bacon Grease | After the Requiem, Chomsky answers questions | The Apocalypse’s Apocalypse and Post-Apocalyptic Visions of Sunshine and Blessings | Rev. Hagler's U of R speech and an interview with student organizer Hijazi | Rochester Rally for Palestine | From Ferguson to Palestine to Rochester: the truth perseveres! Rev. Hagler speaks! | New venue found for Palestinian rights speaker after divinity school rescinds invite

Judy Bello Puts Syria In New Perspective

October 4, 2016, activist Judy Bello gave a presentation at Rochester's Downtown Presbyterian Church. About 50 people were in attendance. Bello has traveled extensively in the Middle East to observe the effects of US military and economic policy on the civilian population. Her latest journey was as part of a US Peace Council fact finding mission last July. This was her second time in Syria since 2014. She has paid similar visits to Iran, Iraq and Pakistan. The 60 minute presentation was followed by an additional hour of questions and answers. The event left an entirely different perspective on the crisis than that presented by mainstream corporate media.

Judy Bello on Syria

Q & A

Related: What Islam means to the White Male- Through the lens of a Bullet Covered in Bacon Grease | Military Academy Report a Sham | Ryan Harvey on Europe's Refugee Crisis | Cornel West's "Connecting the Dots: Poverty, Racism, & Drones" | ROC Says "No" to hate and intolerance and "Yes" to refugees

Dept. invites public to make police union contract modification proposals

In a statement that probably ruffled the feathers of police union president Michael Mazzeo,

Rochester Police Chief Michael Ciminelli invited the public to offer contract modification proposals to the department that they can use in their ongoing labor negotiations with the Rochester Police Locust Club, the sole bargaining agent for Rochester Police Department (RPD) officers.“The period to present proposals is not closed,” said Chief Ciminelli. “And again, because we're in contract negotiations we would have to discuss this in executive session but if you would like to sit down with us and discuss specific ideas we're still in a position to take proposals.”

Chief Ciminelli invited the public's ideas on how to change the contract between the City and the Club at a Public Safety Committee Meeting held on September 21, 2016.

The committee meeting, usually held in executive session, was opened to the public after a video showing RPD officers brutalizing multiple people went viral. One individual, Lentorya Parker, was tackled from behind by an RPD officer as she was complying with police orders. The incident happened near Avenue A and Hollenbeck Street on September 15. A sole civilian video of the incident was posted online. The videographer, Clarence Thompson, was arrested for Obstruction of Governmental Administration and Disorderly Conduct even though he was more than 10 yards away from the police and not interfering with their activities.

Video courtesy of Clarence Thompson

The meeting was shut down by the public after City Councilmembers had questioned police for more than an hour, while no public input was allowed.

Watch the Democrat & Chronicle Facebook Live video of the Public Safety Committee Meeting (Rochester Indymedia has it's own footage with better audio–will update soon)

Since Mr. Thompson's video went viral, the police department, in conjunction with the District Attorney's office and the City, has released the Police Overt Digital Surveillance System (PODSS) camera footage as well as four body worn camera (BWC) videos. One of the videos has an officer comparing Ms. Parker to “an animal.” See the RPD blue light surveillance camera footage and the four BWC videos below:

Blue Light Surveillance Camera Video Footage

RPD body worn camera footage #1

RPD body worn camera footage #2

RPD body worn camera footage #3

RPD body worn camera footage #4

The most recent contract between the City of Rochester and the Rochester Police Locust Club expired on June 30, 2016. According to the contract, the agreement is automatically renewed “from year to year” unless either party notified the other of any “intention to change, alter, amend or terminate this contract.”

If the meeting that took place on September 21 is any indication, then one of the two signing parties is interested in changing the contract. One possible reason for the need to re-negotiate the contract is for the need to incorporate an article pertaining to the use of police BWCs and their associated procedures and protocols for the officers represented by the Club. There are several reserved sections in the BWC policy that have been explained by city officials as pertaining to ongoing negotiations between the department and the Club. Of course, one question to ask is, who is representing the public interest in these negotiations?

Breaking down the current contract

The expired 2016 contract contains 34 articles and two appendices, one on discipline guidelines and the other on hospital and surgical health benefits.

The Club represents all officers at the ranks of police officer, investigator, sergeant, lieutenant, and captain with minor exceptions. This represents the “bargaining unit.” The club is an agency shop, which means that all Club members must pay dues. If an officer decides not to be a member, then they are liable to pay a fee to the Club, “from time to time.”

Three of the most important articles, important for the public and democracy, are Article 20 Discipline, Article 21 Members Rights, and Article 30, Section 8: Defense and Indemnification of Police Officers.

Article 20, Section 1: Departmental Investigations and Bill of Rights pertains to any Professional Standards Section (PSS) (or similar entity) investigation of an officer accused of misconduct and the “rights” accorded to the accused police officer in those investigations.

Article 20, Section 1 lays out the specifics of an investigation that is targeting a Club member. The contract stipulates that any interview with the accused officer “shall be at a reasonable hour,” when the officer is “on duty,” unless the “exigency of the investigation dictates otherwise.” The contract does not indicate what counts as an exigency.

The interview, according to the agreement, will preferably be held at police headquarters and the officer in question is allowed to have the investigator's name, rank, and command, the name and rank of the investigator conducting the interview, and the identity of all people present during the interview.

Before an interview occurs, the officer is granted access to all of their own submitted reports that relate to the investigation. Also, before any interview is conducted, the officer “shall be informed of the nature of the investigation” and “sufficient information,” shall be provided to the officer prior to any interview conducted. The contract doesn't define “sufficient information” or tell us what information specifically will be shared with the accused officer.

The accused officer “shall be given 48 hours advance notice of any interview,” unless the nature of the investigation “requires immediate attention.” Immediate attention is not defined.

Article 20, Section 1 tells us that the accused officer may hire their own attorney, use a Club attorney, or may be represented by a designated Club member as long as the representative is not named, as a target of or a witness to, the investigation. The accused officer has the right, spelled out in the contract, to waive the above right of representation and may instead represent themselves and make a statement at the conclusion of the interview.

This statement and any subsequent statements made during the investigation can be obtained by the accused officer, free of charge, within 30 days of the interview. A copy may be released to a Club representative as designated by the accused officer.

The City agrees that it will not to interrogate members of the Club regarding any conversations had with the accused officer. The Club also acknowledges that its representative will not delay or impede the police department's investigation.

The accused officer may “electronically or otherwise record” all statements he gives to the police department pertaining to the investigation. Interestingly, civilians who file complaints against officers with PSS also have the right to video or audio record any statement given during the interview. PSS does not make it a point to inform complainants that they have this right when filing complaints against officers.

In the case that the accused officer refuses to comply with the interview, the contract states that department can not offer any incentives or punishments to induce the accused officer into cooperating. There is no legally binding rule that says officers have to comply with the investigation. Furthermore, the contract states that the accused officer “shall not be subject to any offensive language” for refusing to comply with the interview.

The accused officer cannot be “ordered or requested” to take a lie detector or polygraph test.

Article 20, Section 1 continues that before any charges are filed against the officer, they “shall be afforded an opportunity to be heard.” Should the complaint against the officer be sustained, a warning or memorandum may be entered into their personnel file. If the officer feels that such a warning or memorandum was “not justified,” then the officer may respond in writing and have that written statement amended to their personnel file. It is also noted in Section 1 that “such warnings and memorandum are not discipline.”

And just to make sure the contract terms are understood on matters of discipline, the accused officer “shall suffer no reprisals, directly or indirectly, for exercising his rights under the article.” Whether or not a civilian making a complaint has the same rights as the accused officer with regards to reprisals (what civilians call retaliation), is not of interest to the Club, it's members, or officers.

In the event that a complaint against an officer is sustained and discipline is deemed appropriate by the police chief, then the officer would go before a Hearing Board. Forty-eight hours before the hearing, the City and the Club swap lists of potential witnesses and their statements; neither side may contact the other side's witnesses prior to the hearing.

There are three options for the accused officer to choose from in determining the composition of the Hearing Board that would determine any discipline, according to the contract.

The first option is that the Appointing Authority gives the accused officer a list of three command officers above the rank of lieutenant from which the accused officer selects two. The officer in question then gives the Appointing Authority a list of three Club members at rank higher than the officer to be disciplined from which the Appointing Authority selects one. This constitutes the Hearing Board: two command officers and a potentially sympathetic officer. And, according to Article 75 of Civil Service Law, the burden of proof is on the department to prove that the officer committed misconduct.

A second option that the accused officer can choose is the same as option one except that the officer can choose to have a civilian serve on the Hearing Board. In this case, one of the command officers chosen by the Appointing Authority would be replaced by the civilian. The Hearing Board would be composed of one command officer, one potentially sympathetic Club member, and one potentially sympathetic civilian. Police policing police is codified into the policy and procedure for disciplinary hearings within the contract and Civil Service Law.

A third option for the accused officer is to have a one person Hearing Board. In this case a “professional neutral” would be selected from a rotating list of three people agreed upon by the City and the Club. In the event that the accused officer selects the third option, the City (taxpayers) would foot the bill for the use of the arbiter.

Regardless of which option the accused officer selects, should they lose the hearing, they can appeal the decision under Article 76 of Civil Service Law.

There is no statute of limitations for bringing a complaint against an officer to PSS. However, there is a timeframe when it comes to disciplining officers for misconduct. According to Article 20, Section 1 of the contract, “No removal or disciplinary proceeding shall be commenced more than eighteen (18) months after the occurrence of the alleged incompetence or misconduct complained of in the disciplinary charges.” It's worth repeating. No disciplinary hearing against an accused officer can start if 18 months have elapsed from the time of the incident. The exception granted in the contract is that the 18 months doesn't apply if the misconduct in question can be proven in court to “constitute a crime.”

For “minor violations of the Rules & Regulations and General Orders of the Department,” Article 20, Section 2: Command Discipline gives command officers “holding the rank of Major or higher” the power to impose command discipline.

Command discipline constitutes one of the following: “a Letter of reprimand; suspension without pay for a maximum of three (3) days; requirement to work up to three “R-Days” without additional pay; reimbursement up to $100 of the value of property which is intentionally or negligently damaged or lost...; successful completion of a driver training program; or transfer.”

With regards to command discipline, there are three options for the accused officer. They can accept the command findings and punishment; accept the findings but appeal the punishment at something called the Command Discipline Appeal Board (the board consists of two command officers appointed by the police chief and the Club president or some designee of the Club president for a three member board) where the outcome is final; or reject the findings and punishment and elect to have a disciplinary proceeding according to Section 75 of Civil Service Law.

In the case of command discipline, there is also a timeframe for disciplinary action. According to Article 20, Section 2, no disciplinary proceeding can start “more than 90 days after the occurrence of the alleged misconduct.” If the officer can keep their nose clean for a year and not rack up any other command discipline, then the record of discipline “shall be removed” from the officer's personnel file. Once it's removed, the record cannot be used in any way against the officer. In fact, the officer may request that such records are destroyed or returned to the officer.

Article 21, Member Rights isn't any better. It gives complete control of the officer's personnel record to the officer. It explicitly counteracts any attempt at transparency and accountability.

Under Article 21, Section 1, officers can review their personnel file, after writing to the chief, in the presence of an appropriate official. Only complainant names, addresses, and reference sources “shall be deleted from said file” when “it is so deemed necessary.” What the criteria is for necessity is not laid out. The request must be honored in 15 days.

Under Section 2 of the same article, the City agrees that police identification photographs won't be released to the press unless it receives permission from the officer.

Under Section 3, the public can request employment records and any disciplinary proceedings where a current or former officer plead guilty or was found guilty of charges and had a chance to be heard, as according to Section 75 of Civil Service Law.

The City may also disclose, to a requesting party, records of disciplinary charges if the officer has resigned or retired with disciplinary charges still pending. The scrutinized officer does have the right to write a letter addressing the charges and have that letter included whenever a request is made.

Finally, officers, current or former, have the opportunity to review their own history record maintained by PSS. “History record” is not defined within the contract. The only stated stipulation to this part of the contract is that the officer cannot review anything in the record related to an ongoing investigation or one where the officer has been named at the time of the review of their history record.

Aside from Article 20 and 21, Article 30, Section 8: Defense and Indemnification of Police Officers is necessary reading for the public. This article is essentially laying out the terms for the City to legally defend any police officer that is accused of misconduct, which leads to criminal charges or civil suits. This information must be paired with the fact that as of 2015, 93.3 percent of RPD officers lived outside of the City (In 2013 it was 93 percent and in 2010 it was 87 percent). In 2016, the City's Freedom Of Information Law office (FOIL) stated that, "The City/Non-City resident status in not available in the current database; therefore, that item could not be added to the spreadsheet." An appeal is pending. If the people of the City are footing the bill for the misconduct of officers–a supermajority of whom don't even live within the City–then one must wonder why the City doesn't push back in these negotiations and demand that officers get their own insurance.

Article 30, Section 8 states that the City is responsible for paying “reasonable and necessary” attorney's fees, disbursements, and litigation expenses arising out of any alleged activities that occurred while the officer was exercising or performing their duty. According to the contract, the responsibility of the City to pay for the defense of a police officer in a criminal proceeding arises “only upon the complete acquittal of a police officer, the dismissal of all criminal charges against him, or a no-bill by a Grand Jury investigating an on-duty use of a weapon.”

This section notes that the City is responsible for providing a defense for a police officer involved “in any civil action or proceeding before any state or federal court or administrative agency arising out of any alleged act or omission” while the officer was performing their duty. The exception here is that if an action or proceeding is “brought by or at the behest of the City itself,” then the City is not responsible for paying for the legal defense of a police officer. However, this is reversed should the officer prevail in such a civil action or proceeding.

Article 30, Section 8 also provides that the City's attorney, Corporation Counsel, must defend the officer or “may employ special counsel to defend” the officer in “any civil action or proceeding unless the Corporation Counsel determines that a conflict of interest exists.” In the case of a conflict of interest, the agreement states that the officer would be entitled to a private attorney of their choice where the City is required to pick up the bill for the private attorney. What constitutes a "conflict of interest" is apparently at the discretion of Corporation Counsel.

In the case that an officer loses a civil suit, Article 30, Section 8 states that the City “shall indemnify and save harmless [another way of saying that the City is responsible for any losses or liabilities] a police officer in the amount of any judgement obtained against the police officer in a state or federal court or administrative agency, or in the amount of any settlement or a claim, provided that the act or omission occurred while the police officer was exercising or performing or in good faith purporting to exercise or perform his powers and duties.” However, the City is not responsible for losses or liabilities when the officer intentionally commits wrongdoing or if a claim is settled or a judgement obtained as a result of a proceeding brought by the City.

Finally, one last important piece to Article 30, Section 8 is that the City is under no obligation to defend or indemnify an officer if the officer does not cooperate fully with Corporation Counsel and fails to deliver any paperwork, summonses, notices, complaints, or any other legal proceedings within five business days of the officer receiving such notice.

Aside from the three articles noted above, the contract presents other information like salaries. After about two and half years, assuming an officer has completed their training and has been serving for a full year, they can reach step two on the pay scale. Base pay, at step two, means that officers receive $51,798 per year (Article 3, Section 3). After three years of service, the officer gets longevity pay, which amounts to $100 per year for 22 additional years (Article 3, Section 4). They also get a pension, covered by the city, through the New York State Policemen's and Firemen's Pension System (Article 3, Section 5), up to “six calendar months of continual sick leave for any illness or injury not sustained in the line of duty (Article 8, Section 5),” medical and surgical benefits (Article 11), vacation days (Article 10), and educational allowances in police related fields of study (Article 14). Club members also get time and half pay for any court or internal procedure related to the performance of their official duties (Article 15, Section 3) as well as full pay and a leave of absence when called for jury duty or jury service (Article 33). The City agreed as well to provide all weapons, ammo, equipment, leather goods, and the replacement or repair of lost or damaged weapons and equipment (Article 12, Section 6). All this and overtime pay (Article 15).

The police like to believe their own myths when they tell the public they have the most dangerous job out there. The benefits they receive certainly make it seem as if that were true. Except that, according to the United States Department of Labor statistics, the profession of police officer doesn't even make it into the top 10 most dangerous jobs.

You can read the whole contract here.

Why police “unions” are not unions

There are some who would say that police officers are a part of the 99%. And perhaps by some metrics, such as income, they are economically in the realm of the 99%. However, their interests and actions are not aligned with the labor movement. Nor are their actions aligned with other movements that represent the 99%, such as the civil rights movement or the Black Lives Matter movement of today. Police are the guardians of capital and have been doing their jobs effectively for hundreds of years.

Kristian Williams, in his book Fire The Cops! asks us not to consider percentages, such at the 99%, but rather to consider class identity. In his essay “Cops and the 99%,” he points out that the wealthiest top 1 percent of the population controls 34.6 percent of the country's wealth. He expands the percentage to the top 10 percent, who control 73.1 percent of wealth. The point isn't the numbers. The 99% was clever in that it created a kind of commonality for use by vast numbers of people. And that's really what it represents. According to Williams, “It is just another way of saying 'the people' or 'the masses'.”

In the pyramid scheme that is our economic system, Williams tells us that a small minority of people are at the top. These are the capitalists who are “cultivating vast quantities of wealth.” In other words, profit. This wealth is allocated according to the desires of the capitalists. Some of it goes back to making productive wealth–or capital. The rest of us are forced to sell our time to bosses in order to make a set wage that we can use to live on. The wage represents a fraction of the actual wealth produced.

According to Williams, if the capitalists are making money and we are getting something, then things are good for the capitalists. However, if the capitalists start losing money, well then you've got job cuts, plant closures, and wage theft. (Sometimes, Williams notes, the government will actually bail out the capitalists by giving them handsome amounts of wealth.) If you're thinking that this is an “enormous scam,” Williams agrees. It's called capitalism. How do you keep the racket going?

The role of police, at its most basic, is to keep this system of extortion in place, and in particular, to keep it in place by using surveillance and violence to control those portions of the population most likely to cause it trouble. In other words, to control workers and poor people and–since the U.S. is stratified by race as well as class–people of color in particular.

So even though cops might come from working class families, where they work for wages, “have low social status, and are organized into unions,” Williams observes that the cops are left in a bit of an “ambivalent class position.” In Rochester's case, the rank of police officer is the lowest rung of the police hierarchy. However, when looking at the institution in relationship to the City or even society, Williams argues that cops–even the ones at the bottom of the hierarchy–are “a part of the managerial apparatus of capitalism.”

Williams notes that the modern police force came out of slave patrols where “militia-based groups” were charged with “keeping slaves on plantations, and just as importantly, preventing revolts.” This history gives a good understanding about police motives: the institution's “dual social function–preserving racial and class inequality–is a much better indicator of what the police are going to do than either the law or concerns about public safety.”

It is no surprise, then, that collective action intended to address these social inequalities is met with police repression. The cops, historically, have been the enemies of both the labor movement and the civil rights movement. They've attacked picket lines, broken up demonstrations, raided offices, tapped phones, opened mail, sent informants and agent provocateurs into organizations, jailed organizers, and assassinated leaders. That's the job. That's what they do. Why should we expect any different?

So, if society is going to have an armed and dangerous group of people that are tasked with maintaining race and class inequality, then the last thing the elites of society want is to have that group mingle with the labor movement and social justice movements. To prevent this from happening, beginning back in the early 20th century, “cops began to show an interest in collective bargaining.” As they watched other workers and municipal employees gain the right to organize, “police commanders very cannily opened an avenue that would simultaneously allow for negotiation and avoid the dangers of police joining a broader labor alliance.”

With regards to the Locust Club and its origins, Charles Clottin wrote a paper titled “The Evolution of the Rochester Police Department Locust Club.” The Club formed on April 17, 1904 with its primary concern being the promotion of the “social, physical welfare and the material improvements of members of the Rochester Police Department.” (I'm not sure who Clottin is, but his paper is linked on the Locust Club website.)

Clottin tells us that there was a coal strike in March of 1904 that may have been an impetus for the creation of the Club in April: “The coal strike caused officers to work picket lines to ensure the safety of the strikers and to keep the peace. The strike may have inspired officers to organize to improve their own working conditions.” Clottin does not elaborate on the strike, how well officers ensured the safety of the strikers, or how effective they were at keeping the peace.

Going back to Williams, he offers some reasons, from the perspective of local authorities, as to why police-specific unions are a good thing:

They institutionalized negotiations, which allowed conflict within the police department to be resolved through legalistic, routinized means. Further, separate unions meant that the police could be always treated as a special case during budget planning and contract talks, granting them pay, benefits, and pensions far better than those of other government workers. Police unions organized the cops as cops rather than as workers, encouraging an identification with the police institution as a whole and cementing a kind of vertical solidarity. And for all these reasons, police unions allowed local governments to keep the police in reserve, away from the main body of the labor movement, and ready to act against striking workers.

Contract negotiations between command officers (the department), civil authorities (the City), and the rank and file officers (the union) become, as cited by Williams, “as sociologist Margaret Levi puts it, an exercise in 'collusive bargaining'–taking the outward appearance of conflict, while actually operating in terms of a union/management consensus.” These entities bargain away the interests of the public and simultaneously extend the power and control of the department and the police union. Williams notes that this collusive bargaining process is used to “insulate the police from meaningful oversight and accountability.” This is accomplished through plausible deniability between commanders and the rank and file beat cop who may be engaging in severe misconduct. While the policies and procedures of the department protect the command officers, the union comes out and vehemently defends the rank and file officer from any kind of discipline or even negative judgement.

Michael Mazzeo, the Locust Club president, will occasionally stand before the press and blatantly lie about incidents and defend egregious officer conduct. One instance of this is seen in the arrest of Emily Good who videotaped a racially motivated traffic stop and was arrested ostensibly for videotaping, and more recently, Lentorya Parker, who Mazzeo claims struck an officer, which led to her being brutalized and the civilian videographer, Clarence Thompson, to be arrested.

Williams notes in Our Enemies In Blue, page 228, that “This arrangement allows for the formal appearance of rigorous command and control while maintaining maximum discretion at the lowest levels of the organization.”

This kind of collusive bargaining tosses democracy and the public interest to the curb. Williams argues in Our Enemies, page 236, that “as institutions of violence become more autonomous, they isolate themselves from democratic control.” As police departments “gain influence over policy and social priorities, they inhibit the representative aspects of other parts of the government.” In short, “Blue Power reduces the possibility of democracy.”

Stop the cops and fund Black futures

"We must focus on structural changes," states Charlene Carruthers in the Forward to the Agenda to Build Black Futures released by Black Youth Project 100 (BYP100) in February of 2016. "The 'American Dream' of meritocracy has never guaranteed prosperity for Black people in America."

BYP100 and other people of color/Black-led activist organizations around the country have called for the defunding of punitive and carceral systems such as police and prisons and to instead prioritize the funding of Black futures–essentially creating Black economic stability and sustainability in communities across the nation.

Locally, Building Leadership And Community Knowledge (B.L.A.C.K.) is engaged in projects to develop Black sustainability as well as showcasing Black businesses around Rochester.

Cause N'FX garden, organized by one of B.L.A.C.K.'s founders, Tonya Noel, has three primary goals. According to Ms. Noel, the garden is meant to "1. Provide healthy affordable food options by creating green spaces in area that are otherwise food deserts; 2.Educate the public on how to produce and prepare their own healthy food. Moving us towards a more sustainable and self sufficient system; and 3.Encourage local restaurants to invest in the communities they serve by buying local produce."

Recently, at the corner where the garden is, the RPD put up a surveillance camera. The camera was installed shortly after the arrests of 73 during a Black Lives Matter protest demanding justice for Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, India Cummings, and "all those who have lost their lives to police brutality and misconduct." The protest was held on July 8, 2016.

B.L.A.C.K. has also had two successful Black Business Marketplaces (and is planning their third). The Marketplaces showcase Black businesses in Rochester and allow people to connect with the owners and their products and services. Black businesses are also promoted by the organization through its social media channels.

Ms. Carruthers continues in the Forward to the Agenda: "Our communities deserve reparations for systemic violence and harm, good jobs, stabilizing development in our communities, support for the women who hold our households together, and support and protections for queer and trans* folks."

In Rochester, the proposed 2016 - 2017 budget for the police department is about $92.7 million. Aside from the undistributed expense line in the budget, the Rochester City School District is the only institution that receives more dollars (hundreds of millions) than the RPD.

Looking at the salaries of the police department in 2015, we find that the top five commanding officers (the Chief, two deputy chiefs, and two police captains), combined, make a total of $526,340.36. That's the sum of their base salaries without benefits or overtime. Consider what half a million dollars could do to fund Black futures, or, for that matter, what $92.7 million could do.

The Agenda lays out several recommendations to build Black futures: reparations for slavery; honoring Black worker rights and supporting a living wage for all Black workers; divestment from "local, state, and federal policing and prisons;" an end to all fines for "minor crimes, misdemeanors, and administrative fees for probationers and parolees;" valuing Black women's work through universal childcare and access to full reproductive healthcare; support and protection for Black trans* people; and lastly, promoting the "economic sustainability" of Black communities, while eliminating the displacement of people of color from their homes, neighborhoods, and communities.

In her lectures regarding the abolition of the Prison Industrial Complex (PIC), Angela Davis is very clear that without economic freedom, there can be no Black liberation. "Freedom is still more expansive than civil rights," she said at a speech she gave at Davidson College on February 12, 2013. "In the sixties there were some of us who insisted that it was not simply a question of acquiring the formal rights to fully participate in a society, but rather it was also about the forty acres and the mule that was dropped from the abolitionist agenda in the nineteenth century." The Davidson College speech can be found in a new book of hers, Freedom Is A Constant Struggle.

Part of the struggle is to understand how the systems around us work so that we may find those points of weakness to pressure for more freedom. The police union has a lot of power in Rochester and, as stated above by Chief Ciminelli, there is still time to push back against the police contract currently being negotiated. It's a contract that makes opaque what should be transparent and loots the public of its money, while kicking democracy and police accountability to the curb.

Enough is enough.

Take Action

Make a police union contract modification proposal!

Feel free to send your modification proposal via email to Police Chief Michael Ciminelli and City Councilmember Adam McFadden! If you like, you can also post it on the Office of the Mayor Facebook page, Adam McFadden's Facebook page, and/or the Rochester Police Department's Facebook page.

If you feel compelled to post your contract negotiation proposal to social media, please include the hashtags #RochesterIndymedia and #MyContractChanges.

Related: The People’s New Black Panther Party (Interview from What's Hot) | Policing doesn’t need reforming. It needs to be abolished and created anew. | Inside the City's Negotiations with the Police Union | How Union Contracts Shield Police Departments from DOJ Reforms | The Problem with Police Union Contracts | When Police Unions Impede Justice | Forced reforms, Mixed results | World of Inquiry #58 Soccer Team Protests National Anthem | Coleman and wife brutalized by officer Brian Cala | Garden Under Surveillance By Rochester Police Department | B.L.A.C.K. addresses community after 73 protesters arrested | How to Help Black Lives Matter (and Other Causes) While Dealing with Mental Health Issues | A Jury of One's Fears