“Family Trouble”: The 1975 Killing of Denise Hawkins and the Legacy of Deadly Force in the Rochester, NY Police Department

Abstract: This paper examines the lineages of police violence, family trauma, and police reform through a case study of the Rochester police killing of Denise Hawkins in 1975. Michael Leach, a 22-year-old, white police officer, responded to a “family trouble” call involving a domestic dispute between Hawkins and her husband. When the 18-year-old, 100-pound Black woman emerged from the apartment, she held a kitchen knife. Within five seconds, Leach had shot and killed her, later claiming she endangered his life. Though Hawkins’ name is included in lists of Black women killed by police, little is known about her life and legacy. Using newspapers, police records, and oral history, we examine activists’ attempts to scale the call for justice for Denise Hawkins to the national level, the police department’s defense of Leach as the true victim in the incident, and the city leaders’ compromised efforts to establish a civilian oversight of police. Within the context of Rochester’s robust history of resistance to police violence, we argue that the reform efforts of the late 1970s ultimately failed to redress the police use of deadly force. Furthermore, when Michael Leach killed again in 2012—this time shooting his own son, whom he mistook for an intruder—his defense attorney successfully depicted Leach as the sympathetic figure. In shifting the focus to Denise Hawkins, this work contributes to the Black feminist call to memorialize Black women killed by police and suggests that the policies that protect the officers who use deadly force cause widespread, intergenerational harm to officers and their victims.

1. Introduction

On the evening of 14 November 1975, 1000 people gathered at St. Simon’s Episcopal Church on 6 Oregon St. in Rochester, NY, demanding justice for Denise Hawkins. The church regularly offered its space to civil rights organizations. Three nights prior, Rochester Police Department (RPD) Officer Michael Leach shot and killed an eighteen-year-old mother. Leach, a 22-year-old rookie cop, was responding to a “family trouble” call intending to intervene in an escalating argument between Hawkins and her husband. When he arrived, Hawkins emerged from the apartment, and within five seconds she was dead. Leach said the 5-foot tall, 100-pound woman “lunged” at him with a “dagger”, which made him feel endangered, so he fired his .38 caliber weapon into her chest (McGinnis 1975a). Police Chief Thomas Hastings concluded that Leach acted in accordance with police policy.

Before the large crowd in downtown Rochester, Rev. Raymond Scott, president of FIGHT (Freedom Integration God Honor Today), a major civil rights organization, demanded Leach’s suspension. Scott pointed to eyewitness testimony that contradicted Leach’s account of events. He questioned the RPD’s choice to send an inexperienced officer like Leach to a family trouble call and criticized the three other officers on the scene for failing to intervene. Scott voiced long-standing concerns of the community—that city officials would whitewash the evidence and yet again fail to redress acts of police violence (McGinnis 1975b).

The large turnout at St. Simon’s indicated that Hawkins’ killing in 1975 struck a chord with residents in a way other police killings had not; Scott recognized an opportunity to mobilize their outrage. FIGHT joined the Black Community Coalition to encourage a unified and deliberate response to Hawkins’ death. Signaling intentions to shine a national spotlight on Rochester’s policing problems, the Coalition contacted the US Justice Department to investigate. Rev. Scott introduced Fletcher Graves from the New York City office of the Community Relations Division of the Justice Department to the crowd. Graves promised to work with Black leaders and Rochester city officials to investigate the circumstances of Denise Hawkins’ death. Residents were loud and angry, at times interrupting Scott, and critical of his trust in government agencies. Some young people wearing black ski masks disrupted the meeting and demanded immediate action from the city of Rochester. His voice hoarse from yelling over the crowd, Scott urged the crowd to “control their anger” and “not to act out of emotion but only according to a plan” (McGinnis 1975a).

This paper charts Denise Hawkins’ death in Rochester NY, a city with a powerful police union, a long history of police violence, and nationally recognized models for successful Black economic development. In partnership with Hawkins’ family, the Black Community Coalition threatened to make Rochester a national example of police violence and compelled city lawmakers to address the problem. Though Denise Hawkins’ death fell from public view by 1976, her story resurfaced in 2017 as a rallying cry for Black Lives Matter activists in New York City. Participants in the People’s March carried signs detailing the circumstances around her death, noting “this is not an isolated incident” but a pattern that continues to disproportionately impact Black and brown people (Anonymous Contributor 2015). The inception of the Black Lives Matter Movement in 2014 and a series of high-profile police killings of Black men have energized activism around, as well as scholarly and journalistic attention to, the intersection of racism and policing in the United States (Zuckerman et al. 2019).

National outrage about police killings tends to focus on Black men, and Black women killed by police are often minimized or underreported in the media (Williams 2016). In 2014, the African American Policy Forum (AAPF) launched the #Sayhername campaign to combat the silence around police killings of Black women. Along with Kimberlé Crenshaw, the AAPF contends that to document and highlight Black women’s stories is to refuse “the loss of the loss” of their lives (Crenshaw and African American Policy Forum 2023, p. x). In #Sayhername: Black Women’s Stories of Police Violence and Public Silence (2023), Crenshaw argues that racial justice movements “cannot address a problem we cannot name. And we cannot name it if the stories of these women are not heard” (Crenshaw and African American Policy Forum 2023, p. 13). Historical and contemporary oppression subjects Black women and girls to what Deborah King calls “multiple jeopardy”, wherein exploitation on the bases of race, gender, class, ability, and other factors multiply in impact (King 1988). When histories of anti-Black violence center on men, Black women’s experiences of state-sanctioned violence as well as intra-communal violence are sidelined; an incomplete portrait of the oppression and exploitation of Black women and girls results (Lindsey 2023). Among cases of police violence against women in the US since 1942, 59% involved Black women, despite comprising only 12% of the general population.1 A 2001 Bureau of Justice Statistics report found that police killed Black women at an annual average rate of 1% from 1976 to 1998 compared to white men and women and Black men (Brown and Langan 2001). The low percentage of Black women killed by police represents underreporting of these events by police and state mortality surveillance systems (Loftin et al. 2003). In Rochester, from 1973 to 1979, the RPD killed 8 people, most of whom were young, Black men. Denise Hawkins was the only Black woman among them (Croft 1985). The essence of the #Sayhename campaign is not simply to memorialize Black women killed by police but to “confront, contest, and dismantle the interlocking systems of state power that continue to routinize and normalize those killings” (Crenshaw and African American Policy Forum 2023, p. 16).

Though Denise Hawkins is the first on the #SayHerName list of Black women killed by police in the last fifty years, little is known about her impact (Crenshaw and African American Policy Forum 2023, p. 177). Using oral histories, newspaper accounts, and government records, this article seeks to restore Denise Hawkins to the history of gender and police violence and to contextualize her story within the histories of Black economic development, community activism, and police reform. Denise Hawkins’ life epitomized the aspirations and optimism of the Black middle class unique to Rochester in the 1970s— evidence of the successful efforts of Black economic development that generated pride from Black organizers and Rochester’s corporate giants alike. Her death reinforced the boundaries of progress and acted as a stark reminder of a police policy that trains officers to shoot to kill, protects them in the aftermath, and continues to leave Black residents disproportionately vulnerable to police violence. Policing innovations since the 1970s resulted in community policing, a diversified force, and greater accountability (Mastrofski and Willis 2010). Scholars and activists acknowledge that Michael Brown and the uprising in Ferguson marked a distinct shift in the national conversation about policing (Robinson 2020). Rochester was once again in the national spotlight during the 2020 uprising—a global response to the killing of George Floyd by Derek Chauvin in Minneapolis—when the RPD killed Daniel Prude during a mental health crisis and collaborated with city government to cover it up. The city erupted in weeks-long protests calling for justice for Daniel Prude that were met with expired tear gas canisters, rubber bullets, dogs, batons, tanks, and arrests. In 2021, a team of complainants filed a class action lawsuit against the city of Rochester for excessive use of force by the RPD, not only during the 2020 uprising but for decades. Denise Hawkins’ name is included in the suit to demonstrate a long history of racist police abuse (Fanelli 2021).At the time of this writing, the case is ongoing.

In returning to the 1975 case, the continuities between past and present become troublingly clear. In Mirage of Police Reform, Robert E. Worden and Sarah J. McClean argue that reforms, even with wide support and good intentions, hardly result in substantive change (Worden and McClean 2017). Reforms fail for many reasons (Skogan 2008). Public disapproval of police misconduct wanes (Weitzer 2002). Police unions obstruct progress. Some simply “fade away” (S. Walker 2012, p. 60). Samuel Walker contends that reforms will only work if they transform the organizational culture of a police (S. Walker 2012, p. 66). Though the problems of policing are national, departments are locally operated; therefore, resolving the problems requires a keen understanding of the social and political context of each (Monkkonen 1982, p. 576). In many ways, the story of Denise Hawkins and the Rochester Police Department of the 1970s is tragically ordinary–familiar racist tropes that exaggerate Black women’s criminality and police officers who are trained to kill endangered Black women then as now. However, Rochester’s history of rather exceptional radical activism points to ways in which sustained public pressure and national scrutiny served organizers well in 1975 and may provide hope for the future.

This paper argues that seasoned Black organizers in Rochester mobilized public outrage after Hawkins’ death, which leveraged the specter of the city’s 1964 uprising— which brought Rochester’s racist policing into national view—and threatened to once again tarnish the city’s reputation and place the police department under federal scrutiny. When public pressure was strong, Rochester seemed on the edge of another nationally recognized rebellion. However, another death in the family prompted Hawkins’ parents to withdraw support, and organizers followed their lead. In the absence of sustained national attention and community pressure, the city passed comprehensive police reforms in 1977, including establishing a Complaint Investigation Committee (CIC), which were compromised to appease the police and did little to stop police violence or redress the harm caused by police. Furthermore, Michael Leach, the officer who shot and killed Hawkins, was exonerated by a grand jury and never faced legal or criminal consequences. In 2012, Leach shot and killed his own son, Matthew, mistaking him for an intruder. To receive a lesser charge and a lighter sentence for murdering his son, Leach claimed to suffer from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) from killing Denise Hawkins decades earlier. Framed as a tragic victim of circumstance, Michael Leach was sentenced to just six months in jail. Though a flagship city for Black economic development and police reform in the 1960s, the Rochester, NY of the 1970s was not able to protect Denise Hawkins, her family, or the family of the officer who shot her.

2. Black Activism and Police Reform in Rochester, NY

In the early 1960s, the midsize upstate New York city of Rochester was a national leader in police reform efforts and Black economic development. In 1963, after a series of police brutality incidents in the Black community, Rochester was the second (to Philadelphia) of five cities to participate in the first wave of civilian-led, independent police oversight boards (McKelvey 1993, pp. 249–50). When continued police violence sparked an uprising in 1964, Rochester became the second (to Harlem) of a nationwide series of uprisings that became known as the Long Hot Summer. In Rochester, the uprising lasted three days and involved heavy National Guard presence, 976 arrests, 350 injuries, four deaths, and over USD 1 million of property damage (Flamm 2016, pp. 210–14; Buttino and Hare 1984, p. 7). Black community leaders channeled collective frustration about over-policing, employment discrimination, and housing segregation into an “organizing frenzy” following the uprising (Hill 2021, p. 123). FIGHT, a working-class organization, sought Black self-determination through individual and cooperative capitalist gains within the Black workforce. Action for a Better Community (ABC) represented the city arm of Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty; it was tasked with dispensing federal funds. The Urban League arrived later and represented the interests of the Black middle class (Hill 2021, pp. 123–29). Employment opportunities for Black workers, won by organizations like these, drew migrants to Rochester. The city’s Black population tripled between 1950 and 1970 (Hill 2021, p. 12). These changes, however, did not eliminate deeply entrenched racial inequality or police violence; if anything, they highlighted them.

FIGHT targeted the racist employment practices of Eastman Kodak Company, which was founded and headquartered in Rochester. Despite Kodak being a national model for corporate policy, its executives espoused racist ideas and refused to hire Black people (Murphy 2022). Minister Franklin Florence, the then-president of FIGHT, mobilized a multi- faceted attack on Kodak’s reputation, soliciting multiple national Christian denominations to join them in making a spectacle at the company’s annual board meeting in 1967. When Kodak balked, Florence invoked the specter of 1964, promising that “what happens in Rochester in the summer of ’67 is at the doorstep of [the] Eastman Kodak Co” (Loh 1976). Stokely Carmichael, leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and champion of Black Power, visited Rochester to register the SNCC’s support for FIGHT’s campaign. National news outlets including the Associated Press and the New York Times covered the feud between Kodak and Black activists (Hill 2021, p. 114). FIGHT knew the city of Rochester, and the Eastman Kodak Company feared negative press and continued to raise the stakes with provocative direct actions and coalition-building with churches and other organizations. Kodak submitted to pressure from FIGHT in June 1967 and opened an unprecedented number of jobs to Black people (Hill 2021, p. 122). FIGHT also partnered with a rival Rochester corporation, Xerox, to establish FIGHTON, a community develop- ment corporation (CDC) designed to create ownership opportunities for and within Black communities (Hill 2021, p. 134). FIGHTON stood as a national model for Black-power inspired CDCs [community development corporations]” (Hill 2021, p. 130). According to Laura Warren Hill, “Rochester emerged as a pioneer in the quest for Black economic development” (Hill 2021, p. 86) and a “national symbol in the fight for the soul of Black capitalism” (Hill 2012, p. 46). FIGHT successfully exploited Rochester’s fear of another 1964 and the attendant national spotlight; these lessons would remain salient for FIGHT’s leadership after the death of Denise Hawkins.

Despite decisive victories against employment discrimination, poverty and violence disproportionately persisted for the Black residents of Rochester and across the United States into the 1970s. Desegregation and federal civil rights legislation failed to reverse deeply entrenched economic and social disparities laid by a long history of racism in cities across the United States (Cashin 2004). As a result, uprisings continued in midsize cities like Rochester into the early 1970s: the United States witnessed 1949 uprisings in 960 segregated communities between 1968 and 1972 (Hinton 2021, p. 10). Uprisings after 1968 remained local—locally managed and locally remembered—and therefore tend to be minimized or forgotten (Hinton 2021, p. 12). However, Elizabeth Hinton defines the post-1968 era as the “crucible period of rebellion”, in which midsize cities like Rochester confronted state-sanctioned violence that continues in the 21st century (Hinton 2021, p. 12).

High-profile instances of state-sanctioned violence in upstate New York fomented additional distrust. In 1971, State Police and National Guardsmen brutally repressed an uprising of incarcerated people in the Attica Correctional Facility (Thompson 2016). That year, RPD officers harassed and arrested an increasingly organized coalition of activists, religious leaders, and students—most of whom were white—who staged anti-Vietnam war protests across town (Rosenberg-Naparsteck 1986). Members of Youth Against War and Fascism (YAWF) understood the RPD as a proxy for Governor Rockefeller and President Nixon, and therefore police aggression appeared to be an arm of the global effort to contain communism and quell dissidents (Gale and Rockowitz 1972). Meanwhile, economic recession, the War on Poverty, and expanded, militarized police departments collided to further impoverish and surveil Black communities across what has become known as the “Jim Crow North” (Purnell et al. 2019; Schrader 2019). In a segregated Rochester, police brutality remained a constant concern in the city’s 3rd and 7th Wards, where most Black people were forced to live (Scott 2008).

By the time Denise Hawkins was killed in 1975, Black organizations in Rochester had grown accustomed to responding regularly to state violence. Rev. Raymond Scott remembered police killings and subsequent uprisings occurring every year during his tenure as the FIGHT president from 1971 to 1976. A younger generation of Black Americans who witnessed their parents take enormous risks to secure the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, felt disillusioned about the limits of that legislation to keep them safe from police violence and de jure segregation in the form of redlining, inherited poverty, and employment discrimination (Rothstein 2018). FIGHT filed complaints about police violence after 1964, but, according to Scott, police “would never volunteer any word on the outcome of their investigations”. And the news failed to report on police violence leaving FIGHT to be the front-line response to citizens’ grievances. Though other organizations existed, “when there was a crisis”, Scott recalled, “when people wanted action, you know, then they looked to the FIGHT organization” (Scott 2008). In the early 1970s, while Denise Hawkins attended Madison High School, FIGHT functioned as a liaison between the city’s government and Black communities afflicted by police violence. “Our primary objective”, Scott said, “was to keep our people from getting killed” (Scott 2008).

3. The Life and Death of Denise Hawkins

Denise Darsal Hawkins (née Roach) was born on 1 February 1957, in Geneva, NY, the second oldest of four children. Her father, Clifford Roach, was a technical sergeant in the US Air Force, so the Roach family lived in France, Panama, Colorado, Pennsylvania, and Arizona before arriving in Rochester, NY. Roach retired from the US Air Force in 1970 and the family chose to settle in Rochester so Mrs. Waverly Roach could pursue a position at the Eastman Kodak Company. The family purchased a home in Rochester’s 19th Ward, a newly integrated neighborhood in the city’s southwest quadrant. Racist real estate practices and restrictive covenants confined Black families almost exclusively to the 3rd and 7th Wards; in 1965, the 19th Ward Community Association (19WCA) formed “to fight racist real estate practices, such as blockbusting and redlining, while purposefully cultivating a neighborhood that is diverse”.2 Black middle-class families employed at Kodak, like the Roaches, were among the first Black residents to move into the 19th Ward, where Clifford Roach still lives at the time of this writing.3 The 19WCA remains one of the oldest active Neighborhood Associations in the US.

In the 19th Ward, the Roach family provided a happy childhood for Denise and her three siblings. Denise remembered growing up in a “home of love”. Her parents were strict. “We had to be in before the streetlights came out [and] we weren’t allowed to start dating till we were like 16, 17”, her sister Ruthie recalls (Kimbrew 2023).

Denise attended two junior high schools before enrolling at Madison High School on Genesee Street in 1971, where she earned academic honors in multiple subjects and won awards in athletics (Kimbrew 2023). She developed a close relationship with her high school principal, Mr. Johnny Wilson. She considered him a father figure, and he called her “‘my child with the $64,000 smile’” (M.J. Walker 1975). She loved to dance and founded a dance club at Madison.

As a teenager, Denise composed poetry under the name “Shasheca” and explored themes of self-love, self-determination, and Black Power. Cheryl Clarke notes that during the Black Arts Movement of the early 1970s, “black woman identity reification poems were legion” (Clark 2005, p. 73). Reminiscent of Mari Evans’ “I am a Black Woman” (1969), Shasheca’s poem “I the Unique Black Woman” identified the intersections of her race and gender as sources of strength (Hawkins n.d.a). Evans described herself as “impervious and indestructible” and beckoned the reader to “Look on me and be renewed”, her visible presence a source of strength for others. Similarly, Shasheca celebrated her Black body: “my keen black eyes my widened nose my thick and lovely lips”. Drawing from these traits, Shasheca proclaimed: “I posess (sic) the power of black, it is in my heart and bound to my soul” (Hawkins n.d.a). The poem concludes with a gesture toward the collective of “all my Black sisters” for whom she offers a hopeful blessing for the future: that they “will be unique too”. At once aware of the persistent denial of Black girls and women and their sense of beauty and self-worth, Shasheca’s poem asserts a key theme of the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and 1970s: simply existing as a Black woman in a society wishing to erase her was an act of resistance.

Shasheca’s poetry extended from the self to society, attendant to power and injustice. In “Boys”, for example, she imagined punching the “silly boys” who pull her hair—“cause it’s only fair” (Hawkins n.d.b). Another poem critiqued white supremacy:

If those people white and pale could paint their faces black would Try to wash the Paint away and Say thank God Im white. (Hawkins n.d.c)

In “Help”, Shasheca adopted the voice of those unable to read or write and critiqued poverty as the root cause of suffering for “Not just me but many more who have to take it because we’re poor” (Hawkins n.d.d).

In addition to her academic and artistic strengths, Denise Hawkins was well-liked among her peers. In her senior year at Madison, Hawkins was runner-up for Homecoming Queen, and her new boyfriend, Louis Hawkins, escorted her to the ceremony. Louis was four years older than Denise, known for his big personality and stylish fashion sense. When Denise first met Louis, she became instantly infatuated. Her parents and high school principal, however, disapproved. They suspected Louis was using drugs, and they worried he would be a negative influence on their daughter. But she was infatuated with Louis, and, although her boyfriend did not attend the school, Denise Hawkins insisted he escort her in place of another Madison High School male student (Henry 2023). Shortly before she graduated in 1974 with a Regents diploma, she learned she was pregnant. She planned to become a nurse but decided to marry Louis. Against Clifford Roach’s wishes, Waverly Roach signed the parental consent form so seventeen-year-old Denise could get married.

Louis and Denise Hawkins wed on 21 January 1974. Denise was a few weeks shy of her 18th birthday, and Louis was 22 (City of Rochester 1974). On 19 June 1974, Denise gave birth to Louis Hawkins Jr., known affectionately to his family as “Little Louie”. That summer, they moved to the FIGHT Village apartments at 103 Joseph Avenue. FIGHT Village was an apartment community run by the FIGHT organization to offer Black residents affordable housing. Joseph Avenue was a historically redlined neighborhood north of the city center and one of the locations of unrest during the 1964 uprising. Flemish Ashford, who was the president of the Fight Village Tenants Association (FVTA), told a reporter that, by the time the Hawkinses moved in, “there was no trouble there, no rowdiness” (Family, friends ask how 1975). Denise planned to get involved in the FVTA and applied for a position at the US Post Office. In the fall of 1975, a young wife and mother, Denise Hawkins had big plans for her future.

On 11 November 1975, Denise, Louis, and Little Louie Hawkins visited Denise’s cousin Adrienne Turner at the Apollo Apartments on Thurston Road in the 19th Ward. Together with Miranda Roach, Denise’s sister, they spent the evening listening to music, drinking whiskey, and dancing. Miranda recalled that “no one seemed intoxicated”, but, at some point, Louis whispered a suggestive comment to her (‘Didn’t mention weapons’ in call 1975). Denise stepped away from dancing with Adrienne to offer Miranda a glass of wine and to ask “‘What did Louis tell you?’” (‘Didn’t mention weapons’ in call 1975). Miranda told her sister what happened, and conflict between the couple escalated. Denise found a knife in the kitchen, and Louis grabbed a chair; Miranda determined that “‘things were really getting out of hand’”. The argument moved from the living room to the kitchen. “‘Denise and Louis were really at it with each other’”, Miranda said, “‘I felt someone was going to get hurt’” (Lovely 1975c).

Afraid for her sister’s safety, Miranda called the police department at 8:37 pm. The police would later claim that she told the dispatcher “husband and wife quarreling. Wife’s got a dagger–something. Please hurry up’”, but Miranda insisted “‘I did not mention any weapons or anything like that’” (‘Didn’t mention weapons’ in call 1975). The dispatcher exaggerated the situation, telling police there was a gun involved (Willis 1976). Michael Leach, a 22-year-old, white officer who had been on the force for 18 months, responded to what became a labeled “family trouble” call. Officers understand anecdotally that family trouble calls present greater risk for law enforcement compared to other calls; however, data do not support this perception (Nix et al. 2019). But, because “family trouble” calls carry the reputation for being dangerous, officers respond to them differently (Westley 1970, pp. 60–61; Black 1981, pp. 126, 141, 162–63). According to Jessica Gillooly, family trouble calls receive “High-priority” status and “prime the police for a serious encounter” (Gillooly 2022, p. 768). Officers in Chicago were found to be frustrated with, and reluctant to respond to, family trouble calls, especially those from poor or working-class neighborhoods, which officers associated with violence (Westley 1970, p. 60). Typical family trouble calls involved violence against women by their husbands, and officers’ delayed their response to avoid any harm to themselves and hoped the situation would resolve itself (Black 1981, pp. 113–17). Officers devoted even less effort to calls involving Black people and were more punitive toward Black couples (Black 1981, p. 187). The nascent “battered women’s movement” of the 1970s was building power and awareness of domestic violence throughout the 1970s, but Black women remained underserved by the criminal justice system and unprotected from domestic violence (Koyama 2006).

Leach arrived at the location of the family trouble call with three other officers: his partner, John Roberts; acting sergeant John Donlon; and officer Thomas Nagel. Before entering the building, Roberts called the dispatcher to confirm: “‘Did you state there was a gun involved?’” and the complaint bureau dispatcher replied, “‘Yes, weapons involved’” (Willis 1976). At this point, misinformation from the dispatcher compounded officers’ expectation that the family trouble call would pose a risk. Three of the four officers had drawn their service revolvers as they approached the door of the basement apartment, and Donlon brandished a shotgun (M.J. Walker 1975).

Meanwhile, inside the apartment, Miranda continued to deescalate the situation. She took the knife from Denise and hid it in the oven, out-of-sight. The argument seemed to be calming down, and Miranda never believed Denise had any real intention to harm her husband. Miranda turned to see Denise had opened the oven and retrieved the knife and threatened her husband again (‘Didn’t mention weapons’ in call 1975). The physical threat that Denise at 5 feet, 2 inches and 100 pounds posed to her husband was likely minimal, and, at some point, he grabbed her wrists, while she held onto the knife, to subdue her. Miranda tried to restrain Louis, and Denise decided to leave the apartment. She struggled to open the door but managed to get out. As Miranda held Louis back inside, she heard a gunshot in the hallway. “‘I pushed Louis aside, and run out immediately after, and my sister was shot’”, Miranda said (‘Didn’t mention weapons’ in call 1975).

Denise Hawkins may not have known the police were on their way, and it was unlikely, given the commotion ensuing inside the apartment, that she expected four officers with their guns drawn to approach as she fled her husband. Miranda never heard police announce themselves or direct Denise to drop the knife. In a sworn statement Miranda said,

“there wasn’t a sound. . .Denise just ran out, and I like heard the gunshot and I ran out. Louis ran out behind me. Before she got out that door, she shot, and I said, Louis didn’t do that. Where did that shot come from? And I ran out and there is my sister against the wall. . .and I saw the policeman’”. (‘Didn’t mention weapons’ in call 1975)

Michael Leach had fired his .38 caliber service revolver one time into the chest of Denise Hawkins, and the young mother of 18-month-old Little Louie died in the apartment hallway (Leach predicted 1975).

News reports of the tragedy from Communicade, one of Rochester’s Black newspapers in circulation, emphasized the loss of a beloved family member. A front-page headline lamented a “Young Mother Shot By Police” and the phrase “‘family trouble’” appeared in quotation marks in the first and final lines of the news article. The article emphasized her familial roles—as mother, sister, and wife—to highlight her interdependence with others in the community and to suggest a widely shared sense of loss. Though police labeled Miranda Roach’s call for help as a “family trouble” call, Communicade and Black activists countered that the police only caused trouble for the family by killing a young mother in their response (Young mother shot 1975).

4. Police Response

The police perspective dominated the white, mainstream newspaper coverage of Hawkins’ death and subsequent investigation. Rochester’s dailies, the Democrat and Chron- icle and the Times-Union, relied on police reports in their coverage of the police violence. Their reporting centered on Michael Leach, not Denise Hawkins. Headlines about the case identified Leach by name more often, such as “Leach: ‘She was Definitely in a Threatening Position,’” (Leach: ‘She was Definitely. . .’ 1975) and “Leach’s statement” (Leach’s statement 1975) headlined a full reprinting of his version of events. Media coverage characterized him as a noble victim of a dangerous profession, simply trying to defend himself. In a statement given shortly after the incident, Leach said, ‘She was attacking me and there wasn’t anything else I could do but fire. . .I know that if I couldn’t have shot, I would have been stabbed’” (Leach predicted 1975). The Democrat and Chronicle described Hawkins as “a screaming woman [who] lunged at him with a foot-long knife when she came out of the apartment” (Leach predicted 1975). In another description, she “held the knife raised in her right hand, the blade was pointed toward Leach in a downward stabbing position” (Cooper 1975). The mainstream newspapers repeated menacing terms such as “lunge” and “dagger” to exaggerate the threat she posed to the officers when she emerged into the hallway.

After the shooting, the RPD rallied behind Leach. Police Chief Thomas F. Hastings issued a brief statement declaring Leach’s use of deadly force to be “‘justifiable under the circumstances’” (Policeman in shooting 1975). Police internal affairs investigators and Assistant District Attorney Michael R. Saporito Jr. concluded, after a five-hour investigation, that there was no evidence that Leach required discipline or dismissal. The RPD reassigned Leach to a desk job and gave him paid leave “because he was emotionally upset” after killing Hawkins (Leach predicted 1975).

In the days after the tragedy, Michael Leach expressed that he felt absolved of any wrongdoing and assured of RPD support. Confident his actions were appropriate, he said, “‘If I’d have done something wrong, the department would have filed charges against me’” (Leach predicted 1975). He described killing Denise Hawkins as an inevitable feature of law enforcement, “an unfortunate thing that happened. . . I’m sorry that it happened, but it does happen”. Professional obligation required him to respond to the supposedly dangerous “family trouble” call—so he claimed to be simply carrying out his duty at great potential risk to himself. The RPD orchestrated a media narrative that legitimized Leach’s version of events, likely in anticipation of the subsequent investigation. Leach’s confidence may have stemmed from the fact that the RPD officers rarely faced charges. Not one of seventy-nine complaints of police misconduct from 1963 to 1970 resulted in disciplinary action (Myers 1984). Rochester’s policing challenges followed national trends in the 1970s. Police departments across the United States considered themselves “helpless victims of Black aggressors,” which hampered efforts to reduce police presence in Black neighborhoods (Hinton 2021, p. 103).

To investigate whether Michael Leach was a victim of Denise Hawkins, and therefore justified in using deadly force, Monroe County convened a grand jury. FIGHT president Rev. Raymond Scott said “‘we have no confidence in the Monroe County grand jury completing an impartial review’ of the Hawkins’ shooting. The grand jury has very little, if any, credibility in our community’” (Lovely 1975b). Rochester Mayor Ryan attempted to assuage these concerns with a pledge for transparency. He promised to make the grand jury report widely available. But Scott noted that police could “‘cover up’ details and withhold evidence”. FIGHT planned to mobilize community support to publicize counternarratives to the police version of the facts.

5. Community Response

Black organizers formed the Black Community Coalition, including a group of mothers, the Fight Village Tenants Association, FIGHT, and prominent Black leaders including James McCuller, Constance Mitchell, Councilmember-elect Ronald Good, County Legislator David Gannt, and former FIGHT president Franklin Florence. They stressed unity among groups and individuals. Together, they stifled the call for mass protests while emotions were high. The impulse for urgent action was particularly strong among younger Black activists. The City Council could not act until the grand jury report was submitted to the public, and they urged Black leaders to be patient. Council members also needed to consider political expediency; the new Democratic majority on the council hoped to strike a balance between “appearing to give in to black pressure” and “refus[ing] to negotiate”, which would have resulted in mass protest (Lovely 1975a). Black activists and organizers mobilized to ensure the Hawkins’ case was not “‘whitewashed’” or forgotten while the investigation was underway (Young mother shot 1975).

The Black Community Coalition started by building visible power around the goal of pressuring the city to suspend Leach. They contacted the US Department of Justice to investigate the situation in Rochester, who sent Fletcher Graves, a member of the Com- munity Relations division of the New York City Regional office (Young mother shot 1975). Meanwhile, the FIGHT Village Tenants Union, which represented Hawkins’ neighborhood, called for the suspension of all four officers (Young mother shot 1975). On November 14, at noon, a multi-racial coalition of about 50 community members spoke to the City Council to demand Leach’s suspension until the end of the investigation (Young mother shot 1975). That evening, a crowd of 1000 people gathered at St. Simon’s Episcopal Church for a com- munity meeting about Denise’s case led by FIGHT. A Black church built in 1921, St. Simon’s founded some of the community organizations that shaped the political landscape of the 1960s, including FIGHT, and organized in the city after the 1964 uprising.4 FIGHT President Raymond Scott appeared alongside Fletcher Graves and informed the crowd that the US Justice Department would investigate Hawkins’ death. The large crowd was outraged and young people, in particular, expressed urgent disapproval of Scott’s apparent acquiescence to the slow pace of justice. Scott reminded them of the imperative to channel their emotions strategically and collectively. He noted that public pressure was already working: Michael Leach had been temporarily relieved of duty in response to the people’s demands (McGin- nis 1975a). The Black Community Coalition hoped to continue to empower the community by mobilizing residents into a unified grassroots movement to pressure the City Council from within, while also looking to national platforms to pressure Rochester from outside. The Coalition believed that, if the city erupted into a disorganized uprising too soon, they would lose their key bargaining tool. The power lay in the threat of rebellion, and, as long as the possibility of another 1964 uprising loomed, leaders could brandish its specter to bend elected officials to the public will. Scott understood the imperative of an organized, deliberate response.

Thinly veiled political messages reached hundreds of attendees at Denise Hawkins’ funeral the next day at the Antioch Baptist Church (M.J. Walker 1975). Some of the words shared at the service focused on the personal details of Hawkins’ life. In contrast to the media portrayal of Denise as a violent, dangerous Black woman, loved ones remembered details of her life. Johnny Wilson, principal at Madison High School and Denise’s mentor, emphasized the family element. He characterized Hawkins as a person with deep “respect for the family institution” (M.J. Walker 1975). He believed that the “family trouble” call that led to her death was tied to her abiding loyalty to family. Wilson said, “‘I believe she was trying to preserve the family institution when she died” (M.J. Walker 1975).

Rev. Willie Cotton, the pastor of Antioch Baptist Church which Denise Hawkins was in the process of joining, delivered an impassioned eulogy with thinly veiled political messages. He lamented “‘living in a world of trouble’” and urged the crowd to seek Jesus Christ to find solace. He offered hope, claiming, “‘You can conquer hate with love’”. He implicated the police in Hawkins’ death, stating: “‘Those running around with guns are not going to be the winners’” (M.J. Walker 1975).

The grand jury investigation was set to begin November 26. They called for Leach’s suspension. They relied on Graves, who lived in NYC, to help publicize Rochester’s fight for justice for Hawkins at the national level. They contacted Rev. Jesse Jackson, an acolyte of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr, who headed Operation PUSH (People United to Save Humanity) in Chicago. Jackson asserted his skill for public campaigns following King’s assassination and developed an impressive reputation for maneuvering the media and organizing direct action campaigns to redress racism across the United States. Jackson pledged PUSH would “definitely get involved” with FIGHT to “put an end to such senceless killing (sic)” (Group takes role 1975). As the coalition grew to include PUSH and with investigation from the Department of Justice, Rochester’s fight for justice for Denise Hawkins emerged at the national level. Jackson’s attention to the Hawkins’ case increased the pressure on the city to respond appropriately and to avoid another 1964 uprising—because the nation was watching. This kind of attention intimidated the Rochester Police Locust Club. The Locust Club, the union for Rochester police, represents officers from the rank of Police Officer to Captain; its name comes from the hardwood used in the department’s first issued billy clubs.5 Timothy Hill, the Locust Club president, criticized the decision to remove Leach from active duty: “it appears that the threat of riots and violence from extremist groups who disregard due process of law has caused the city administration to buckle under pressure and change the duty status of Officer Leach’” (Policeman’s status 1975). Making it personal, Hill added: “‘We assure the citizens of the city that we will not tolerate Rev. Scott’s attempts to run the Police Department’” (Policeman’s status 1975). While the grand jury investigation continued, the Black Community Coalition believed that, as long as they remained unified in purpose and action, their political power functioned as a tool to push for police reform.

On behalf of the local NAACP chapter organization, President Howard W. Coles and Executive Secretary Theophilus E. Tyson echoed the calls for a unified effort for justice: “We are in full accord with the public opinions indicating that for no reason can we see that the police officer involved was justified in shooting this woman”. The NAACP noted “the community at large is greatly disturbed about the facts involved in this incident”, in part because the information was unclear but in part because the story was so familiar. Rochester residents experienced “many such incidents in the past entailing similar appeals and protests” to no avail. Describing the community as “anxious” and “struggling. . .to bring the citizens of this city and the Police Department to a point of peaceful co-existence”, Coles and Tyson were particularly concerned about the youth of Rochester who were already affected by “too many unfortunate past experiences”. They noted that Hawkins’ killing “negatively affected and so greatly disturbed” young people the most” (M. Johnson 1975). They lacked faith in the judicial processes, like Scott, and expected the cycle of police violence to continue unchecked. The Judicial Process Commission, a group of 30 community members formed to improve the criminal justice system in Rochester, urged the City Council to address the fact that city residents distrusted the RPD to resolve misconduct internally. They called on the City Council to appoint a panel to make information about the Hawkins’ shooting available to the public and “‘establish and maintain credible means of receiving and investigating complaints” about the RPD (Council urged 1975). Thirty Black clergy, members of the Interdenominational Ministerial Fellowship, called for a similar process for evaluating and changing the RPD so that city leaders “‘can better guarantee to Rochester citizens that this kind of incident (the shooting) will not be repeated’” (Council urged 1975). Broad support for a civilian review of the police gained support as organizations and individuals unified in the wake of Denise Hawkins’ death.

On Friday night, 21 November 1975, more than 600 community members filled the pews at the Immaculate Conception Church to support the parents of Denise Hawkins. When Waverly Roach, Denise’s mother, stood to speak, the crowd erupted in a standing ovation. The family announced a plan to sue Michael Leach for the death of their daughter. Willian Kunstler agreed to represent them. Kunstler was a famed civil rights attorney whose flamboyant style and willingness to defend unpopular causes in the name of justice earned national notoriety in cases such as the Chicago Seven, Attica prisoners, and Kent State survivors. Biographer David J. Langum notes that Kunstler’s opponents regarded him as the “most hated lawyer in America”, celebrated and loathed for “his willingness to do battle against the government, to throw a monkey wrench into its well-oiled machine of oppression” (Langnum 1999). Kunstler’s legal skill, but more importantly his public profile, elevated the effort to seek justice for Denise Hawkins. Kunstler announced he would also pursue a civil suit to secure federal oversight of the recruitment and training of the RPD. Raymond Scott said that FIGHT wanted “‘to see that justice is done. . .that this type of nonsense doesn’t happen again”. He promised to make demands on the City Council and escalate to the Department of Justice in a civil rights case. Waverly Roach urged the crowd to see Denise as a “‘symbol to all you young people’” about the costs of violence (Lovely 1975d). With Black leaders and the Roaches behind him, Scott told the crowd, “‘You must not allow this issue to die’” (Lovely 1975d). The number of supporters combined with the high profile of William Kunstler increased pressure on the city of Rochester to act swiftly. Timothy H. Hill, president of the Locust Club, said officers were “extremely nervous” about Kunstler’s ability to bring the national spotlight and federal intervention to their department (Lovely 1975a). Meanwhile, the RPD continued to feed reports to news outlets emphasizing Leach’s innocence and Denise Hawkins’ menacing actions. Leach returned to active duty on December 7 (Shore and Cooper 1975).

On December 11, the grand jury investigation exonerated Leach, finding he acted in self-defense when he killed Denise Hawkins. Because police are trained to use deadly force when they feel endangered, the jury determined Leach’s actions to be in accordance with the police policy and state law. Raymond Scott distrusted the report, noting it was “‘basically the same as the report the police gave after the shooting’” (FBI says 1975). The Black Community Coalition requested an independent FBI investigation of Hawkins’ death. Hugh Higgins, head of the Rochester FBI office, treated the case as a top priority and came to the same conclusion as Monroe County: Leach was innocent.

Black community activists continued to escalate pressure on the city of Rochester by deploying an economic boycott from their arsenal of strategies. They called for a “Black Xmas”. Protesters distributed flyers downtown, inviting shoppers to boycott all stores and shopping plazas: “Remember, the taxes you pay on the merchandise you buy pay the salaries of those who kill you, misrepresent you, and trick you. Join us in a Black Xmas to assure a brighter tomorrow’” (Boycott called for 1975). In the midst of the Christmas holiday shopping season, activists expressed their disapproval of the grand jury’s decision by wielding the power of their pocketbooks.

Meanwhile, the Black Community Coalition produced a Joint Statement with the City Council that advanced eight proposals for a citizen’s committee to review and improve the RPD’s response to crisis calls and to misconduct allegations, their firearms policy, and their training “in multi-racial neighborhoods”; to conduct a review of officers and an expansion of the Family Crisis Intervention (FACIT) program; to curate a list of “non-white and white clergy to be on call to assist in the resolution of family crisis problems”; and to ensure more Black cops in Black neighborhoods (Joint statement 1975).

As Black organizations unified to demand justice for Denise Hawkins, counter-protests and harassment attempted to derail the movement. The Locust Club attempted to control the public narrative and filed a temporary restraining order on the release of further information about the case to the public (Joint statement 1975). Other actions targeted FIGHT leader Rev. Raymond Scott directly. On November 23, someone left a severed deer head on the steps of the Holy Trinity Baptist Church just before Sunday services began. A note, stuck with a nail between the eyes of the deer, read: “This could be Reverand (sic) Raymond Scott” (Deer head 1975). A week later, police arrested Scott on outdated charges of petit larceny in a nearby suburb. The executive director of the Urban League, William Johnson, Jr., called it a “reprisal”, saying, “‘I find it difficult to believe that this action was insulated from Minister Scott’s active leadership in the Denise Hawkins Killing’” (Scott’s arrest 1975). Johnson likened Scott’s arrest to the FBI surveillance of civil rights leaders like Dr. King and the Black Panthers. He said, “We are greatly disturbed that anyone who questions the misconduct of police will have their past carefully scrutinized in order to uncover any incident that can be used against them”. Johnson denounced the RPD’s “gestapo-like tactics” and urged “black and white citizens of this community who believe in democracy” to protest Scott’s arrest (Scott’s arrest 1975).

Community members harassed Denise’s family as well. The telephone at the Roach family residence rang constantly. Ruthie remembers “evil phone calls” threatening violence to the family as they grieved. They “were calling us ‘niggers’” and threatening that “the rest of us would be killed” if the family pursued the suits against the Rochester Police Department (Kimbrew 2023). During this tumultuous time, Little Louie lived with his grandparents. Ruthie Kimbrew remembered Little Louie as a helpful, loving child. She said, “He was so smart. He had a lot of my sister’s characteristics. He was always helpful, well spoken, well mannered. He was almost like the perfect little kid. And he was so proud when he made A’s” (Kimbrew 2023). Waverly continued to work with activists in pursuit of justice, and Clifford remained skeptical about incurring any further harm on his family.

Beset by grief, Denise Hawkins’ widower, Louis, frequented the Roach family home in the weeks following her death to visit his son. Louis considered moving to Chicago with his brother and taking Louie with him. Clifford and Waverly Roach wanted Little Louie to remain with them and pursued full custody of their grandson. On December 30, 1975, Louis came to their house to retrieve Little Louie. Ruthie, Denise’s younger sister, remembers sitting next to Louis on the couch and urging him to leave. Tension escalated among the grief-stricken members of the family still mourning the loss of their beloved Denise and trying to raise her toddler. Louis refused to leave, and Clifford Roach returned with a shotgun. According to Ruthie, the men exchanged harsh words and, when Louis stood up and appeared to reach for the gun, Clifford shot and killed him. The family dragged Louis’ body to the sidewalk and phoned his mother and then the police (Kimbrew 2023). In a matter of six weeks, Little Louie became an orphan.

Clifford Roach was charged with killing Louis Hawkins. When police arrived, he was arrested and held on USD 10,000 bail. Unable to pay, he sat in the Monroe County Jail for two months. Because of the circumstances of the case and Roach’s spotless criminal record, his attorney, Charles Crimi, advised him to take a plea deal. Clifford, with his family’s safety in mind, took the deal and pleaded guilty to second-degree manslaughter. The judge gave him time served with four years of probation. In turn, he lost his job as a mail carrier for the US Post Office (D. Hawkins husband shot 1975). This additional layer of tragedy, combined with the relentless threatening phone calls to the family home, pressed Mr. Roach to remove the family from the public eye. The Roach family dropped the lawsuits against Michael Leach and the city of Rochester, severed ties with William Kunstler, and retreated from activism. Without the family’s support, the agitation for justice for Denise Hawkins waned. After this, news coverage of the case dropped off; national pressure on the city evaporated; and, according to Ruthie Kimbrew, the death threats against the Roach family ceased (Kimbrew 2023). The Roaches retreated to private life, raising Little Louie in Denise’s childhood home. Little Louie had been diagnosed with myocarditis and congestive cardiomyopathy, and in June 1980 the family learned he would not live much longer. Waverly Roach said, “‘I think he knew. He told me he was going to be in heaven with his mommy and daddy and not to worry about him’” (Family suffers new loss 1980). The day before he died, he insisted his grandmother give his toys to the children in the Cancer Center and ICU (Kimbrew 2023). He died in late October 1980 at Strong Memorial Hospital at age six. Within five years, Denise Hawkins’ entire immediate family was dead. The Times-Union described Little Louie’s death as the loss of “the youngest survivor of a family whose tragedies were part of Rochester’s history” (Boy, 6, dies 1980).

6. Policy Reform in the Wake of Denise Hawkins’ Death

The tragic death of Denise Hawkins provided sufficient cause for city leaders to revive efforts to establish a civilian oversight of the police that began more than a decade earlier. In the 1960s, police departments across the US experienced a significant crisis of legitimacy, owing to internal redistributions of professional power and external criticism from civil rights protestors. In this period of disruption, departments across the country recontoured policies, examined racial dynamics, and restrained officers’ individual discretion (Agee 2020). In this context, Rochester established its first civilian oversight board in 1963, follow- ing three instances of police violence against Black residents (Forsyth 2022a, 2022b, 2022c). Its Police Advisory Board (PAB) was comprised of nine Monroe County residents who investigated complaints of police misconduct and recommended disciplinary actions to the chief. Though the PAB could not discipline officers, it could hold public hearings to pressure the city manager to implement recommended discipline. This board pioneered civilian oversight efforts in the early 1960s, the second of its kind in the US to Philadelphia, followed by Washington, DC, Kansas City, and Denver (Coxe 1965; Philadelphia advisory unit eyed 1964). Representatives from New York City visited Rochester before constituting their own board (N.Y. City group 1964; Philadelphia advisory unit eyed 1964). The distin- guishing feature of this wave of civilian oversight boards was their independence—not only from the police but also from the procedures of internal review tasked with addressing misconduct allegations within police departments (Police advisers continue 1964).

Critics understood a civilian review to be an unnecessary impediment to the day- to-day operations of law enforcement. After the 1964 uprising in Rochester, the FBI, led by J. Edgar Hoover, blamed the inability of the police to stop “riots” on police advisory boards. The FBI report on the New York summer riots of 1964 argued that “where there is an outside civilian review board the restraint of the police was so great that effective action against the rioters appeared to be impossible” (Federal Bureau of Investigations 1964, pp. 13–14). A Rochester Times-Union editorial agreed, demanding that supporters of the PAB prove the board was not hindering public safety (City must answer 1964). Meanwhile, the Locust Club slowed the work of the PAB by filing a lawsuit claiming the PAB possessed unconstitutional power and asked the court to enjoin the board from taking any further official action (Rochester Police Locust Club v. City of Rochester 1965; Vogler 1965). Between 1965 and 1969, the Locust Club stalled the PAB with lawsuits. Unable to review cases while a legal action was pending, the PAB responded to only 79 complaints in seven years (compared to Philadelphia’s 206 in that time) (Coxe 1965). The New York State Court of Appeals affirmed the constitutionality of the PAB, and the US Supreme Court declined to hear the Locust Club’s appeal. By 1969, the PAB was free to resume business, but its reputation had been tarnished and public support had declined. Several board members resigned, their seats remained vacant, and the mainstream press called for its abolition. In 1970, Stephen May, the newly elected Republican mayor, defunded and abolished the board (It’s official 1970). Rochester residents once again lacked any credible process to handle complaints of police misconduct. Police violence continued.

The federal government mentioned civilian review boards in two reports issued in 1968 amidst the tumult of urban unrest and declining police legitimacy. The first—the Final Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders—was released in an effort to understand the numerous urban rebellions around the country and the widening gap between Black and white Americans. The Commission found no fault with municipalities establishing independent civilian review boards like the one in Rochester and in fact recommended the creation of such boards in order to “gain the respect and confidence of the entire community” (US National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders 1968, pp. 311–12). The second report—The Challenge of Crime in a Free Society—crafted by the President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice addressed the causes of crime and ways to prevent it, while improving law enforcement and the administration of justice. The President’s Commission found it “unreasonable to single out the police as the only agency that should be subject to special scrutiny” from an external source. The Commission recommended against “the establishment of civilian review boards in jurisdictions where they do not exist” (US President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice 1968, p. 265). The federal government lacked coherence on civilian review.

It was not until 1975, when Michael Leach’s killing of Denise Hawkins caused enough of a spectacle, that Rochester renewed efforts for a civilian review. In January 1976, Mayor Ryan convened the Citizens Committee on Police Affairs to evaluate the RPD’s policies and procedures. He appointed 15 members representing a racial and professional cross-section of stakeholders in the community, including three Black activists—James McCuller (Action for a Better Community and the Black Community Coalition), Constance Mitchell (FIGHT), and William Johnson (director of the Rochester Urban League)—and three RPD officers: Lt. Robert Coyne (president of the Rochester Police Locust Club), Lt. Daniel J. Funk, and Isaac D. Carson (one of a few Black people on the force). They formed three task forces: police operations, training and recruitment, and police social work (Crimi and Willis 1976). Chaired by Charles F. Crimi, the committee was colloquially known as the “Crimi Committee”. Crimi was the son of a Buffalo, NY police officer and worked as a prosecutor at the US Attorney’s Office before starting a private practice in Rochester in the late 1960s. Colleagues regarded him as humble and fair, “a man of unquestionable integrity and a giant in the legal profession” (Sopko 1989). Crimi intended for his committee to cooperate to produce a report that all 15 members could endorse.6 He anticipated that the Locust Club would fight any proposed police reforms but remained confident the committee would meet those challenges (Stewart 1976).

After nearly a year, the Crimi Committee produced the Final Report of the Citizens Committee on Police Affairs. It contained 97 recommendations for police reform, including revised proce- dures for investigating complaints of misconduct, the establishment of a civilian review, revised procedures for evaluating job performance and promotion, and an expansion of the FACIT program. In February 1977, the City Council passed 87 of the 97 recommendations into law, and, within six months, nearly half were implemented (a). The city established the Complaint Investigation Committee—a diluted and powerless version of its predecessor, the Police Advi- sory Board of 1963—designed to review completed internal investigations of police misconduct. The CIC could not receive or investigate complaints directly or compel compliance from the RPD (Frank 1977b). The chief could ignore the CIC’s recommendations without explanation and had final decision-making power over officer discipline. Three-member panels reviewed each completed misconduct investigation; two panelists were command-level officers and one was a civilian who had to be approved from a pool of volunteers trained by the Community Dispute Services of the American Arbitration Association (CDS)—and then vetted by police.7 When the CIC determined an investigation was deficient, it could request further examination from the Internal Investigation Section (Crimi and Willis 1976, pp. 29–30). Unlike the Police Advisory Board (PAB) before it, the CIC held little power to redress police violence or inspire change in the RPD.

Nevertheless, the Locust Club opposed it. Lt. Coyne, the Locust Club president, had objected to the CIC and three other recommendations in the footnotes of the committee’s Final Report. 8 He dismissed a civilian review as “unnecessary” because the RPD already resolved misconduct allegations internally (Akeman 1976). The Locust Club perceived the work of the Crimi Committee to be “against officers’ interests” (Stewart 1977). Deputy Chief Delmar Leach noted the difficulty in balancing the Locust Club’s opposition against the need to find the “right civilian” to sit on the board. “‘We can’t have anyone with an ax to grind’” on the board, said Capt. Thomas L. Conroy, who had served on the Crimi Committee (Frank 1977a). Officers slowed the establishment of the CIC by threatening to strike and disputing their labor contract (Stewart 1977).

Finally, in September 1977, the CIC appointed its first pool of 25 private citizens from CDS to serve on the committee. The Locust Club consulted legal representation to determine whether the civilian review violated officers’ privacy, but Chief Tom Hast- ings promised them that policing in Rochester would remain unchanged. Hastings said, “this committee will only be reviewing complaints, and they won’t be making the actual investigation. . .the final decision will be left up to me just like it is now’” (Frank 1977b). Assured of the committee’s impotence, police resistance waned, and the CIC began its work. In the first year, it reviewed 15 cases. Chief Hastings determined ten complaints to be unfounded, three officers were charged, and two were suspended (Morris 1978).9 Subsequently, excessive force against Black women declined, but this change resulted more from the Crimi Committee’s scrutiny of the police department after Denise Hawkins’ death than any substantive policy change (Croft 1985, pp. 81, 83).

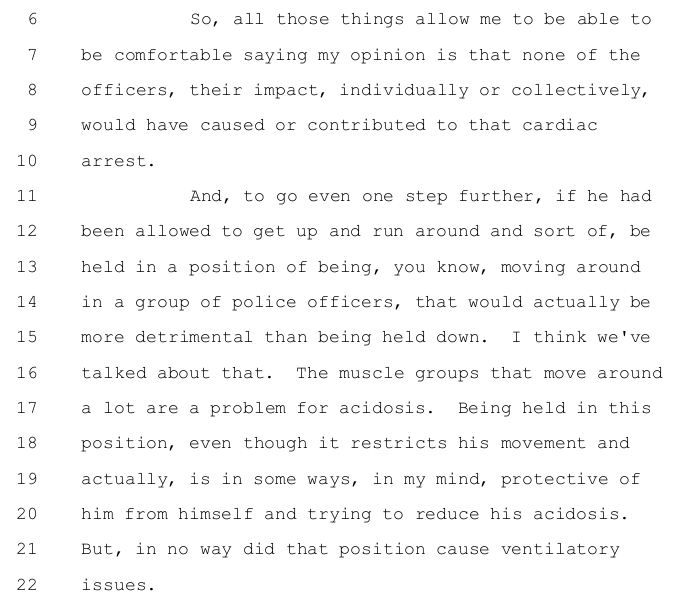

Police use of deadly force slowed but did not stop. Incidents of police violence across New York State in the late 1970s and early 1980s evoked calls for civilian review boards, especially from Black and Latino communities, amid resistance from police unions (Buffalo: Allen 1982; Gates 1979; Kerhonkson: Police group votes against 1984; Mount Vernon: Copithorne 1977a, 1977b; New York City: NYC forms police brutality boards 1984; Gearty 1983; Cop Brutality Board 1983; Hirschfeld 1983; Poughkeepsie: DiFillippo 1984; Suffolk County: McDonald 1980; Bernstein 1976; Troy: McPheeters 1976; Westchester County: Greene 1985). Scholars across disciplines attempted to excavate the tensions between the police and communities of color (S. Walker 1977). On 13 November 1983, the RPD killed Alecia McCuller in nearly identical circumstances to Denise Hawkins. Officer Thomas L. Whitmore and Officer Howard L. Davies responded to “a call of ‘family trouble with a fight’” between McCuller and her boyfriend, Robert Ralph, Jr. According to police, McCuller held a “hunting knife” and chased her boyfriend into the street. Police Chief Delmar Leach, Michael Leach’s father, said later that “the two officers repeatedly warned McCuller to drop the knife, but she did not” (Galante et al. 1983). To allegedly protect Ralph from McCuller, Whitmore shot and killed her. Alecia McCuller was 21 years old.

Alecia McCuller’s death, hauntingly reminiscent of Denise Hawkins’ death, indicated to many community leaders that police reform in Rochester had not gone far enough. Ale- cia’s father, James McCuller, had served on the Crimi Committee. Broken by grief and loss, McCuller said, “‘When the last ounce of breath left my daughter’s body, the Crimi report was dead, D-E-A-D, dead. . . You don’t go up to tombstones and start asking questions” (Crosby and Myers 1984). Other Committee members reflected on the compromises made to complete their work. Charles Crimi recalled concerns that the city would shelve the re- port if the final draft had not borne the signatures of all committee members. Furthermore, to prevent the CIC from getting tangled in court by the Locust Club, they softened their recommendations Eugene T. Clifford, Crimi Committee member and attorney, expressed regret: “‘Some of us would have liked to have civilian representation in a more meaningful way’”. Another member, Monsignor Cocuzzi, agreed: “I wish we had made a greater push [for a civilian review]” (Myers 1984). In 1983, many Black leaders called for community control of policing; however, Rochester City Council responded to the death of Alecia McCuller by simply adding a second civilian seat to the CIC panels (Bunis 1984). Despite its best intentions, the Crimi Committee failed to create substantive civilian review of police violence because of successful resistance from the police union.

7. The Leach Family

After killing Denise Hawkins in 1975, Michael Leach had a long and successful career. He worked under his father, Delmar Leach, who became the police chief in 1981. Michael was promoted to captain in the RPD and, after 25 years on the force, retired in 2001. After that, he worked part-time as a police officer in Perry, NY, a village about 45 miles southwest of Rochester.

In July 2012, Michael Leach was off-duty and vacationing in the Adirondacks with his son Matthew and a group of fellow police officers (Policeman shoots 2012). They shared a motel room at the Clark Beach Motel in Old Forge, NY for the weekend. On Friday night, Matthew came into the room he shared with his father who was already asleep. Mistaking his son for an intruder, Michael Leach fired his department-issued. 45 caliber Glock handgun and killed him (Cop kills 2012). Dan Rivet, Jr., who was the owner of the Clark Beach Motel, and a paramedic attempted to resuscitate him, but to no avail.

Michael Leach called the police just before 1:00 a.m. on Saturday, 21 July, to report the incident. State troopers arrived at the scene. Matthew was taken to St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center in nearby Utica and pronounced dead. Police took Michael to Faxton St. Luke’s Hospital, also in Utica, for what the police called an “unspecified medical issue” (Perry man’s shooting 2012) and the Daily Mail characterized as “mental support” (Policeman shoots 2012). A sympathetic Daily News headline called the killing a “mistake” (Cop kills 2012). The RPD released a statement extending sympathy to the Leach family and asking everyone to keep them in their “thoughts and prayers” (Policeman shoots 2012. Matthew was 37. Six months later, in February 2013, the Herkimer County Court convened a grand jury that indicted Michael Leach on a second-degree murder charge with a 25-years-to-life sentence. He pleaded not guilty, bail was set at USD 200,000, and he spent the night in jail. Perry Police Chief James Case told reporters that Leach was suspended from duty, but otherwise law enforcement revealed very little about the situation to the public (Perry officer charged 2013).

Over the next 16 months, Leach’s defense attorney, Joseph S. Damelio cultivated a new defense strategy: to demonstrate that Leach lacked “criminal responsibility by reason of mental disease or defect.”10 Weeks before the murder trial was set to begin, Herkimer County Court received a mental health report about Michael Leach. Endorsed by expert testimony, the defense claimed Leach suffered Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) from the experience of killing Denise Hawkins nearly 40 years prior. Leach had “recurring nightmares, specifically about a figure entering his home dressed in black” (Retired cop pleads guilty 2014). Leach admitted that once, while alone, he woke up in the middle of the night and fired his weapon into the air (Ex-city cop gets 6 months 2014). Doctors concluded that his “PTSD and sleep-related issues prevented him from appreciat[ing] the risks of sleeping with a loaded firearm” (Ex-police captain sentenced 2014). Because he was half-asleep when his son entered their motel room, the doctors concluded Leach could not have been thinking rationally when he killed Matthew. In this new defense, Damelio characterized Leach as chronically afflicted by mental illness, fearing intruders, and sleeping behind barricaded doors with a loaded handgun at the bedside. Rather than a jumpy two-time killer, Michael Leach appeared as a valiant public servant who had been denied proper mental health care following a traumatic incident on the job, and the defense convinced the prosecution to reduce the charge.

The prosecution reduced the charge to negligent homicide on 4 June 2014, and Leach pleaded guilty. Judge John Crandall of the Herkimer County Court considered Leach’s mental health and offered a far lighter sentence than the 25 years the initial charge carried. Leach got six months in jail, five years’ probation, and required PTSD treatment (Retired cop pleads guilty 2014). Theresa Leach, Matthew’s widow, publicly criticized the family for centering Michael’s trauma rather the tragedy of Matt’s death. Instead of supporting her, she said, the Leach family “constantly worried about you [Michael]” (Ex-police captain sentenced 2014). Linda, Matthew’s mother, rallied around Michael Leach, claiming that punishment for this so-called “mistake” was not what Matthew would have wanted.

Echoing Leach’s defense after killing Denise Hawkins in 1975, news coverage of Leach’s 2014 sentencing cast him as a sympathetic victim of circumstance. The Observer Dispatch in Utica, NY reported that “convicting Leach of a crime and punishing the retired police captain behind bars is something Leach’s family struggles to accept” (Ex-police captain sentenced 2014). By juxtaposing the prestige of a police captain with those “behind bars”, the paper implied Leach suffered an injustice and invited further empathy. The article attempted to empathize with the emotional difficulty of his position: “Although he spent 30 years protecting people as a Rochester police officer, Michael Leach in the end could not protect his most ‘prized possession’—his son” (Ex-police captain sentenced 2014). The Democrat and Chronicle in Rochester offered a similar refrain: “Just as Leach has been living with the lasting impact of that [Hawkins’] tragedy, he will never escape the guilt he has placed upon himself for killing his own ‘flesh and blood.’” His defense attorney, Joe Damelio, reasoned that guilt was punishment enough; because Leach “put himself in his own personal jail”, further punishment from the justice system was gratuitous (Ex-city cop gets 6 months 2014). Herkimer County District Attorney Jeffrey Carpenter expressed hope that Leach could focus on getting treatment after he served his six-month sentence, aware that “if he doesn’t seek help. . .this is something that could happen again” (Ex-police captain sentenced 2014).

The Leach family tragedy highlights the multivalent impact of police violence, not only to the families of victims but also to the families of the officers. It also reveals the stubborn insistence of the media to positively spin violence committed by a police officer, regardless of how sympathetic the victims may be. Denise Hawkins, a bright, young mother, and Matthew Leach, whom Michael considered a “best friend”, receded into the background as news reports concentrated on defending Michael Leach’s innocence.

8. Conclusions

Ruthie Kimbrew, Denise’s younger sister, remembers one childhood Christmas when their mom came home from the department store and surprised the sisters with a toy village of tiny kittens. Ruthie remembers Denise being so happy: “We must have played those dolls every day forever”, she recalled. Kimbrew continues to miss her sister almost 50 years later and now she bears fresh grief from the recent loss of her mother, Mrs. Waverley Roach, who died in 2022. “[My mom] went through a lot and our whole family has gone through a lot” as they continue to reckon with the cascade of events set off on 11 November 1975. Ruthie is the last living Roach sibling: her brother and sister both died from chronic conditions. She takes solace in the fact that “our love has been bonded through all the family”, and her extended family remains close (Kimbrew 2023). The problem of police violence in Rochester and across the US remains unresolved. Mayor William Johnson (1994–2005), who, among other notable posts, served on the Crimi Committee in 1976, looks at the long arc of police violence and failure of reform since then:

Once we accept the premise that all police departments are autonomous, we still have the question why in the Rochester Police Department—where there have been so many studies, so many initiatives, so much investment in change—why are we standing in almost the same spot after 50 years? Why can we not show any demonstrable difference? The names change, but it’s still the same scenario. (W. Johnson 2023)

To date, policy changes have had minimal impact on preventing police violence. In 2020, city residents saw body-worn camera footage of the suffocation death of Daniel Prude, who was experiencing a mental health crisis, by seven RPD officers (Albert 2020). In response, residents protested nightly and then weekly for months; police responded with blunt-force weapons, rubber bullets, pepper spray, tear gas, and police dogs (Saturday’s Protests End with 9 Arrests 2020). In 2021, another body-worn camera video showed Tyshon Jones, who was also experiencing a mental health crisis (Boudreaux 2021), shot and killed by another RPD officer with a violent history (O’Connor 2021). The RPD and the Locust Club continue to advocate for the expansion of police power and increased funding; Rochester City Council and Monroe County have increased law enforcement budgets since 2020.

As this case study shows, police violence traumatizes not only the victims and their families but all affected communities—and the legacy is lasting. The Roaches, Hawkinses, Kimbrews, and Leaches all grieve the loss of their beloveds, whose lives were lost at the hands of Michael Leach. Furthermore, the policy changes proposed by the Crimi Committee and adopted by the city of Rochester did not redress that harm or prevent future incidents of police violence. This perspective also reveals the high costs to officers involved in fatal shootings; police training instructs officers to shoot to kill when they feel threatened, and, according to Michael Leach’s defense attorney, he paid the price of his mental health and his son’s life.

This research on a single 1975 police killing of a Black woman bears contemporary reso- nances to deaths at the hands of the police in the 21st century. It demonstrates that much remains unchanged in contemporary policing. Officers remain empowered to use deadly force, they disproportionately target Black people, and Black women are chronically underrepresented in narratives about police violence. Black women remain vulnerable to gendered dimensions of white supremacy that exaggerate their capacity for physical violence and justify the denial of protections afforded to white femininity. While police violence disproportionately impacts Black people, the white supremacy that undergirds it harms everyone, including the agents of the state charged with enforcing it. The story of Denise Hawkins reveals, in no uncertain terms, that all parties involved—civilian and officer, all races, all genders—were harmed by policies that permit police use of deadly force. As a result, the legacy of Denise Hawkins is an invitation to reconsider the assertion from the Combahee River Collective, a group of Black feminists founded the year Denise graduated from high school, who wrote, “if Black women were free, it would mean that everyone else would have to be free since our freedom would necessitate the destruction of all the systems of oppression”.11 Heather McGee recalls in The Sum of Us that “Black writers before me, from James Baldwin to Toni Morrison, have made the point that racism is a poison first consumed by its concoctors” (McGee 2021, p. xxi). McGee demonstrates that policies about housing, employment, the social safety net, crime, and healthcare, which were intended to harm Black people also harm white people. She also prompts a hopeful solution in which people across lines of difference reject two core lies at the heart of American national identity: that power is a zero-sum game and that the “forces selling denial, ignorance, and projection” are inevitable features (McGee 2021, p. 200). Policies that would have protected the lives of Black women like Denise Hawkins and Alecia McCuller would also have saved the life of Matthew Leach and may have saved Michael Leach from a lifetime of PTSD.