Dredging Up the Past on Police Union President Mike Mazzeo

Primary tabs

05/23/13: So, it seems that good ol' boy Mike Mazzeo, Police Union President, is running his mouth again--this time in regards to Emily Good running for Sheriff of Monroe County (for shame, YNN: http://

2011-07-31 19:26:05 -0400: Police union president Mike Mazzeo is no stranger to police corruption, the violation of citizens' civil rights, or media attention. Back in the late 80s and early 90s Mazzeo was a vice squad officer with the Highway Interdiction Team--a squad used to rough up and bust up alleged low-level drug dealers. For all his trouble, he and five other officers--including the police chief--were federally indicted on 19 counts alleging police brutality, conspiracy to violate the civil rights of suspects, embezzlement, falsification of government documents, falsification of employee time cards and other corruption. While he and his four colleagues were acquitted, officer after officer--in both high and low places in the RPD--admitted to the same abuse of power that Mazzeo was charged with. In today's world, when one sees our bold police union president rattling off his rendition of events and forcefully grasping his podium at the Locust Club, it just makes good sense to hear everything he says "with a grain of salt."

On June 30, 2011, Michael D. Mazzeo Jr., president of the Rochester Police Locust Club union, held a press conference to, in his mind, set the record straight as far as the Emily Good case was concerned. While officers banned Rochester Indymedia from attending the press conference at the union hall, we did hear what Mazzeo had to say; many in the community were outraged at the lies and insinuations emanating from his lips.

However, veterans of Rochester's fight to hold police accountable were probably not all that surprised by his slander or arrogance. You see, Mazzeo isn't new to police corruption, the violation of citizens' civil rights, or media attention.

The Federal Indictment

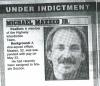

On August 29, 1991, a federal grand jury handed up a 19-count indictment against police officers Scott Harloff, Gregory Raggi, Michael Mazzeo, Thomas Alessi, James O'Brien, and Chief of Police Gordon Urlacher alleging police brutality, conspiracy to violate the civil rights of suspects, embezzlement, falsification of government documents, falsification of employee time cards and other corruption, according to the indictment published in the Democrat & Chronicle on September 1, 1991.

According to D&C and Times-Union reporting, Mazzeo's charges, as summarized by the papers were that he:

- Hit two suspects--an unknown man on Lake Ave. in October of 1988 and Timothy McNulty without justification on Monroe Ave. in June of 1990

- Threatened Alonzo Jackson with a pistol on Joseph Ave. in January of 1990

- Assaulted unknown men on at least two occasions in January of 1990 by placing his pistol against their heads and threatening to shoot them even though they were not resisting

- Used a firearm in relation to a crime of violence in January of 1990

- Embezzled more than $5,000 by being paid for working a 40-hour week but working fewer hours, often ending his day two or three hours early. Told temporary members of the HIT squad that when they left work early, they should avoid Shields, a former bar known to be frequented by other members of the police department. He also told them that if they got into any trouble during the hours in which they should have been on duty, to say they were on "comp," or compensatory time

- Embezzled and stole property worth more than $5,000 from the department and helped others to do the same

Mazzeo, no more than a rookie cop at the time, faced a 40-year sentence and restitution of $1.05 million.

It all started when ex-Rochester Police Chief Gordon Urlacher was arrested on December 18, 1990 by the FBI for embezzlement and conspiracy after Roy C. Ruffin, former aide to Urlacher turned government informant, gave the government secret tape recordings of Urlacher's wrongdoing. A government probe of the Rochester Police Department continued to search for corruption and Urlacher was later indicted with five members of the Highway Interdiction Team for conspiracy to violate the civil rights of drug suspects.

The HIT Squad

According to the D&C, the Highway Interdiction Team, also known as the "HIT squad" or "Jump-out squad"--as I've heard it referenced by veteran community activists--was designed to stop street-level drug dealers. The program was started in April of 1988 amidst the frenzy over the "War on Drugs." Rochester was named as a participant and received a $350,000 grant from the U.S. Justice Department. The teams were staffed by officers detached from their patrol sections for month-long periods with the vice squad doing street-level drug investigations. Sgt. Alessi supervised the teams. Capt. O'Brien supervised the Special Criminal Investigations Section, which included HIT. O'Brien reported directly to Chief Urlacher. Investigator Harloff and officers Mazzeo and Raggi were apart of the HIT squad.

According to a Times-Union report, the "HIT approach was to use an element of surprise in arresting suspected drug dealers. Undercover officers would observe what they believed to be a drug transaction--then jump out of their cars to make the arrest or to conduct an unwarranted raid on a suspected drug house." Further down the article, the journalist explained that judges and district attorneys questioned HIT's tactics, "Yet when the arrests moved from the street to the courtrooms, judges and criminal lawyers found themselves debating whether HIT officers were cutting legal corners." The article concludes by stating that a few of the judges had to dismiss some of HIT's drug cases or suppress critical information because of a lack of probable cause. The HIT squad was dissolved in 1990.

Chief Urlacher Found Guilty

On February 25, 1992, after a three-week trial in U.S. District court, Urlacher was found guilty by a jury on four of six counts of embezzlement and conspiracy. He was sentenced to four years in a minimum security prison. He was also required to pay restitution of $150,000.

Then, on December 7, 1992, Urlacher pleaded guilty to felony charges of conspiracy to violate the civil rights of drug suspects. For his cooperation with the government probe, Urlacher admitted that, "as chief, he knew that a group of vice squad officers were physically abusing criminal suspects, but he did nothing to stop it," according to a D&C article from April 17, 1993.

The Trial Against Five Officers Begins

On January 19, 1993, the trial against the five officers listed in the 19-count indictment began. Jury selection was conducted in U.S. District Judge Michael A. Telesca's court. Of those selected to hear the case, nine were women and three were men. Most of them came from suburban or rural areas and only one was black, while the other 11 jurors were white, according to a D&C article from January of 1993.

The race of the jurors was (and still is) a definite issue in the selection process. Demands for a more representational jury were published in both the D&C and the Times-Union. Could there be justice for the victims--predominantly African-American and Hispanic--with a jury that was 92 percent white attempting to find a verdict in a case involving five white police officers? The D&C ran an article on January 18, 1993 pointing out some of the facts about the jury selection process at that time. Federal juries were selected from a 10-county area where, according to U.S. Census data, people of color who were 18 years or older only represented 8.8 percent of the population within those combined counties. For the victims in this case--communities of color impacted by the HIT squads--the jury selection process seemed blatantly unfair.

Racial make-up of the jury aside, HIT operated predominantly in communities of color within the city; the use of racist police brutality and humiliation was a natural outcome for officers trained by a white-supremacist institution. (Police demographics and hiring policies haven't changed much since 1993--or even since the 1970s as pointed out recently in a memo by City Councilmember Adam McFadden. One only has to look at the demographics of the Rochester Police Department from February of 2010 to get a better picture: race, gender, and residence. This information was obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request to the City of Rochester.)

According to one report from the D&C in September of 1991, "Although law-enforcement officials have said race was not at the heart of the abuses allegedly perpetrated by members of the Rochester Police Department's HIT squads, they now acknowledge that it was a leading factor in a number of the incidents." Some of those incidents included: John L. Chapman having a dreadlock cut from his head; an unnamed youth having "illegal alien" written in ink across his forehead; Ernest Ruise had a "flour-like, powdery substance" dumped over his head; Jackie McKnight had "racial slurs" shouted at him; vice squad members kept a "wooden stick they referred to as their 'nigger stick'" as an office souvenir; Harloff compared Jamaicans to Timex wrist watches stating, "They can take a lickin' and keep on tickin'"; and O'Brien stated that, "Jamaicans aren't citizens--they don't have rights. They should just take them and ship 'em back."

Reverend Raymond L. Graves summed it up nicely, "They focused on blacks and Hispanics," he said. "But I don't think anybody wants to talk about that. That's just going to make everybody uncomfortable." The calls in the community for racial justice, police accountability, and fairness in the jury selection proceeding--and in the case itself--went unheeded.

After jury selection, the trial commenced with government prosecutor Cathleen M. Mahoney depicting the HIT squad as a rogue group of officers that conspired to use excessive force on arrestees between 1988 and 1990. She also stated that in addition to beatings, the police humiliated suspects through actions like dumping garbage on suspects, or writing graffiti on their foreheads. Other accounts stated that police placed vice grips on suspects' testicles, pushed handcuffed suspects down stairways, kicked unresisting suspects, threatened people with live electrical wires, and hit people with boards, metal poles, broomsticks, and blackjacks. "This was no war on drugs," she said. "This was a bunch of police officers who couldn't be bothered with rules."

Mahoney was joined by prosecutors Michael J. Gennaco and Jessica A. Ginsburg.

The defense, led by John R. Parrinello, representing Harloff, with his "impeccable dark suits offset by hot pink straps dangling from his eyeglasses," used a we-versus-them theme, "portraying officers as loyal soldiers in the government's self-proclaimed war" on drugs, according to a D&C article from February 7, 1993. The defense contended that the prosecution was trying to "twist the law" by prosecuting its own soldiers.

Parrinello, who was noted for saying "Objection!" 1,732 times during the first six days of the trial, was almost excused by Judge Telesca for his "rude" and "unprofessional" conduct in and out of court. The judge ordered him to apologize. A D&C article from February 2, 1993 stated that, "In court, Parrinello has acted aggressively, repeatedly shouting at witnesses and prosecutors themselves--and occasionally even shouting objections at other members of the defense team." It concluded, "Yesterday, Parrinello was more subdued than he has been previously." No doubt, Parrinello complied with the judge's order.

Parrinello was joined by four other attorneys: Anthony F. Leonardo Jr. representing O'Brien, David A. Rothenberg representing Raggi, Karl F. Selzer representing Mazzeo, and John F. Speranza representing Alessi.

Corruption Widespread and Public

One of the scariest revelations about this case was the fact that un-indicted officers who were called to the stand to testify against their fellow officers were cross-examined by the defense where it came out that they had also participated in acts of brutality, theft, falsification of documents, and other unscrupulous behavior.

For instance, William F. Morris--former veteran vice squad officer and the prosecution's star witness--testified against his five former colleagues and gave first hand knowledge of 30 incidents where he said police used excessive force against suspects, stole from them, or planted evidence, according to a D&C article from February 12, 1993.

The article continued that on cross-examination, Parrinello asked Morris if he had not yet been sentenced to the misdemeanor he was charged with in a government plea deal. He responded that he had not. Morris had his own share of abusive behaviors, which included participation in thefts from suspected drug dealers and numerous assaults on handcuffed suspects. In agreeing to testify against his colleagues and aid in the government's investigation, he was granted immunity from further prosecution and charged with a misdemeanor.

Another example was the testimony of officer Daniel Gleason. He testified that he witnessed Alessi holding a gun to a suspect's head who was bleeding. However, Gleason said he didn't see Alessi strike Ivan Hawley. On cross-examination, the defense pointed out 10 statements Gleason gave FBI agents and investigators with the city's internal affairs unit that were inconsistent with his statements in court. For instance, he told the internal affairs unit that he never saw or heard about any thefts involving members of the HIT squad. But in court, he testified that he overheard a conversation with Alessi and another officer where Alessi said he took $50 from $19,308 seized at a raid and gave it to an informant for a bus ticket.

Then there was the testimony of Mark Mariano. Among other things, he testified that O'Brien told officers that police officials would treat complaints of excessive force against members of the HIT squad "with a grain of salt," according to a Times-Union article from Janurary 29, 1993. Mariano admitted in court that "he and three other officers, including defendant Raggi, once hit a drug suspect with a flashlight. The suspect, whom Mariano identified as Keith Miller, was lying face-down on the ground, had a cast on one wrist and was not resisting arrest."

In the same article, James "Dean" Thomas, a police investigator, testified that in January of 1988, he witnessed Alessi kick a drug suspect in the mouth, knocking out some of the suspect's teeth. Under cross-examination, Thomas admitted that he denied any knowledge of the assault when questioned by the city's internal affairs unit.

Police brutality, theft, lying to federal agents, and withholding evidence from the internal affairs unit was just the tip of the iceberg. I've mentioned four witnesses and yet, in the first week of this trial, six officers and/or investigators testified against their peers--with immunity--and all had to air their dirty laundry for public scrutiny.

On March 18, 1993, Judge Telesca dismissed three counts in the 19-count indictment: Count 14 that alleged that Mazzeo used his revolver to threaten drug suspects, in violation of their civil rights as well as two counts of embezzlement. The three counts were dropped because of lack of evidence, according to a D&C article from March 19, 1993.

The Verdict, Acquittals, and Sentencing

Then, on March 25, the jury began deliberating the case only to find no verdict by the end of the day. On March 26, the jury came out of deliberations and acquitted the five officers.

Elizabeth J. Borisuk, one of the jurors, said, "It wasn't a case of us thinking these things never happened. We just didn't think there was sufficient evidence."

"There is no justice for people of color in this country, and this trial proves it," said Reverend Lewis Stewart, coordinator of United Church Ministry and its People's Coalition. The papers ran headlines with demonstrating groups demanding justice and police accountability while denouncing the acquittals.

In the end, only three former officers were punished: ex-Rochester Police Chief Gordon Urlacher, former police investigator William Morris, and former police officer Roy Ruffin--ironically, the three officers who cooperated with the government.

Because of Urlacher's cooperation with the government, his plea deal for a felony charge of guilty of conspiracy to violate the civil rights of drug suspects, garnered him a sentence of two more years of prison to be served concurrently with his previous four. Morris, who also cooperated with the government, pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor for participating in the conspiracy to violate the civil rights of drug suspects and received five years of probation for his sentence. He also had to complete 1,000 hours of community service and pay a $25 special assessment. Ruffin, Urlacher's aide turned government informant, pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor embezzlement charge. Ruffin admitted that he stole at least $100 in government money. He was put on probation, restricted from playing pool for money, told to get a job, complete 1,000 hours of community service, and pay restitution of $25,000, of which his accrued wages were divided between the city, which received $3,000, and his lawyer, who received $5,000.

"The public is left with a cloudy and convoluted outcome. The court system decided that Urlacher was more a criminal than Ruffin, though some of the jurors said after Urlacher's 1992 trial that they didn't think so. And, the court system left William Morris a guilty man; meanwhile, the officers accused of the same acts are all innocent. That's the sort of crapshoot common in a courtroom," [Monroe County District Attorney Howard] Relin said. "Somebody will decide to cooperate with police, and the informant will plead guilty, while the target of the investigation may, ultimately, go free," wrote Gary Craig, a journalist for the D&C in a post-trial analysis written on April 17, 1993.

The problem is that these abuses continue to occur. As mentioned above, City Councilmember Adam McFadden called the Rochester Police Department "out of control." In his memo he also pointed out the fact that many people of color are disproportionately targeted by racial profiling and have little to no faith in the civilian review process as of 2011.

The City Pays Out

As the temperature on the government investigation of the HIT squad was climbing, the city paid out at least 10 civil lawsuits brought against it for violations of civil rights and police brutality. Ernest Foxx received a $95,000 settlement after the he brought suit alleging that in 1990 he was beaten by members of the HIT squad. In nine other suits, claiming similar circumstances, the city paid out an additional $131,000, according to a report by the Times-Union published on March 10, 1992.

Then, on June 9, 1993, the Times-Union reported that Maurice James received a settlement of $625,000 after being wrongfully incarcerated for two years in a maximum security prison after being found guilty on drug charges in February of 1989. As the civil rights case rolled along, James' charges were unraveled and thrown out.

Finally, in August of 1993, the city agreed to pay $831,575 for the legal fees of the five acquitted officers.

After his acquittal and completion of the internal police investigation, Mazzeo was retained by the force whereas Harloff had to resign and Raggi retired. Harloff was then hired by the Palmyra Police Department as a patrol officer in October of 1993. Raggi got his full pension and benefits upon retiring. Alessi was fired and O'Brien retired and moved to Florida.

Coming Full Circle

As a requirement for Mazzeo's retention, he had to undergo an "extensive retraining" with little information reported indicating what that meant or who was holding him accountable. He then became a patrol officer and later in his career, the aide to Ronald Evangelista, the former Locust Club president. In a D&C article published on November 19, 2008, Mazzeo was elected to lead the police union by a 4-1 margin as Evangelista retired.

Which brings us full circle, back to Mazzeo, back to Good, back to the corruption of the Rochester Police Department. After investigating this case, it is fairly easy to see why corruption conceals itself so well behind the wall of blue. The fact that police officers are unwilling to denounce corruption or turn in their colleagues for illegal actions, speaks to the uncritical and lock-step nature of police culture in Rochester--and in many other cities across the country. The funny--or perhaps scary--part of this is that when officers are compelled to testify against their colleagues, their own wrongdoing becomes public knowledge and incriminates the whole system--not just a few bad apples. Mazzeo probably feels like he's defending his former, younger, self when he stands next to Mario Masic and contends that Good's rendition of events is fabricated--even though the whole structure Mazzeo functioned in and under crumbled before his very eyes--almost landing him in jail for 40 years with a $1.05 million debt.

My thanks to Davy V. for his help in reporting this story and the Local History Department at the Rochester Public Library.