A brief history of the Police Advisory Board from 1963 - 1970

Primary tabs

[This history is a part of a larger, unpublished report titled, “A comparative analysis of the Police Advisory Board and the Civilian Review Board.” The report will be released sometime in mid-June 2015. [Ed. note--citations are still being scanned and uploaded. Come back for updates. The author wished to thank the kind people at the Local History Department of the Downtown Branch of the Monroe County Public Library System.]

Some events that precipitated the creation of the Police Advisory Board included the cases of A.C. White1 (“...a Negro charged with drunken driving, resisted arrest and suffered a fractured arm among other injuries that took him to the hospital.”), Rufus Fairwell2 (“...a 28-year-old Negro [who] suffered two fractured vertebrae in a struggle with two policemen who attempted to arrest him as he closed the service station at which we was employed...”), and a case of police interference with a group of Black Muslims3 who were having a religious meeting, on the pretext that they had firearms (those arrested were charged with riot and third degree assault).

Below is a skeletal outline of the history of the Police Advisory Board using clippings from the Democrat & Chronicle and Times-Union newspapers. Though not comprised of oral histories or direct source documentation, this history is meant to give clues and a chronology of events according, primarily, to two biased sources, the Democrat & Chronicle and the Times-Union. There were hundreds of clippings and I didn't get to include them all. Many of my citations were against the board, but there were a fair number of clippings in favor of it as well. The clippings left out here may appear in a longer version of this history in the future. For this article, I focused primarily on the work of the board, the legal actions taken against it, and, quite frankly, the vast amount of opposition to it, both white denial of police brutality and anti-Black racism fueling the call for its abolition. Thus begins Act One.

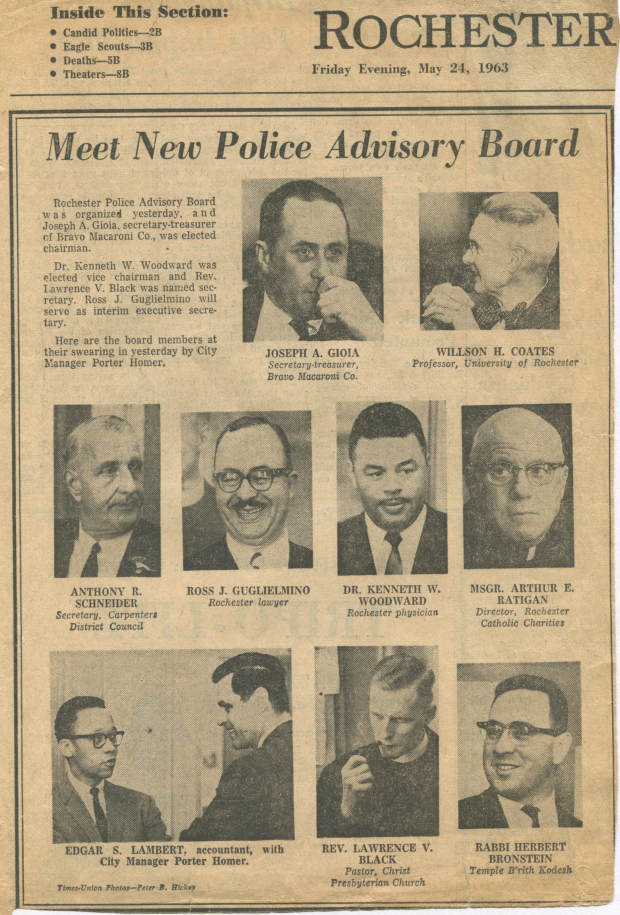

On Tuesday, March 26, 1963, the Police Advisory Board (PAB) was passed into law4 by the Rochester City Council after a “stormy hearing” on March 12. The first nine-member board was appointed on May 20, 19635 and was comprised of three members of the clergy, a pediatrician, an accountant, a treasurer, a lawyer, the Labor Council president, and a history professor. David Gordon, from the Genesee Valley Chapter of the New York Civil Liberties Union, laid out the board's process succinctly:

“The board is empowered to receive complaints from citizens, refer them to the chief of police for investigation, and after it has received the chief's report make its own investigation. If the board does not agree with the chief it must consult with him privately and allow him to make another investigation. If it does not resolve its differences the board must notify the public safety commissioner and city manager. After this carefully controlled process the only power the board has is to make its findings public.”6

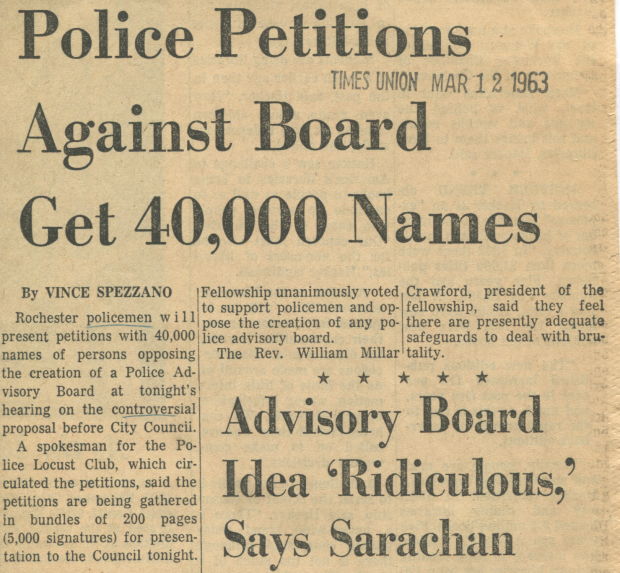

Part of the March 12 storminess was the petition of “40,000 names of persons opposing the creation of a Police Advisory Board” that was submitted to City Council by the Locust Club—Rochester's police union.7 There was also (at least) one full-page advertisement in the Democrat & Chronicle paid for by DeCarolis Trucking and Rental Co., Inc. President Louis J. DeCarolis, Peter V. Ereg, and Russell B. Sanguedolce against the PAB, published on March 10, just days before the March 12 Rochester City Council.8

The first complaint brought to the PAB was ruled outside of its jurisdiction and dismissed on on July 17, 1963.9 According to the legislation, the PAB was tasked with only hearing complaints that alleged “the use of excessive or unnecessary force.” On its first year of operation, according to a Times-Union article from August 7, 1964, the PAB received 20 complaints, dismissed 18 unofficial complaints, and went forward with two official complaints.10 Official complaints were complaints that fit the criteria for review and action by the board. Unofficial complaints were rejected because they fell outside of the scope of the board. Between June 1964 to October 1965, the board accepted 14 official complaints.11 In 1968, the PAB reviewed 10 complaints.12 No cases were reviewed from 1965 to 1968.

Of the 16 official complaints from 1963 to 1965, only three were decided upon.13 In the first case, patrolman Anthony D'Angelo was cleared of using excessive or unnecessary force.14 In the second case, patrolmen Vito D'Ambrosia and Michael Rotolo were also cleared of using excessive force by the board. The board's report stated that the officers “used no more force than necessary.”15 In the third case, John Graham, a black, 19-year-old arrested for public intoxication, stated that four Rochester Police Bureau officers beat him up and used “unnecessary force” while he was in police custody.16 It was the only case, up to that point, where the board and the chief disagreed publicly; this lead to the findings of both Police Chief William Lombard and the board to be placed in the officers' personnel files.17 Upon inspection of the newspaper clippings, no other reports regarding the PAB's case load could be found. The question is, why?

The Police Advisory Board came into existence on March 26, 1963. It functioned for two years weathering a storm of public disapproval18 until, on April 15, 1965, Supreme Court Justice Daniel E. Macken required “the board to show cause why its operation should not be stopped until the suit is decided.”19 He also ordered a “temporary restraining order enjoining the board from conducting any hearings or investigations or performing any other official acts” until the arguments were heard in the show-cause hearing on April 27, 1965.

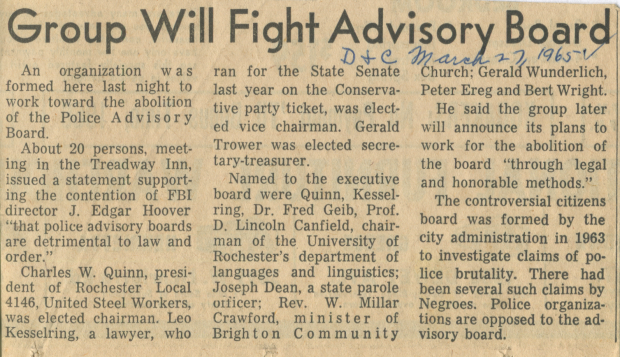

Weeks before the court issued the restraining order against the board, Citizens for Abolition of the Police Advisory Board (CAPAB) formed on March 26, 1965. Taking a cue from the FBI's J. Edgar Hoover, the group put out a statement which said, “police advisory boards are detrimental to law and order.” Charles W. Quinn, president, at that time, of Rochester Local 4146, United Steel Workers, was elected chairman. Quinn told the Democrat & Chronicle that the group would formally announce its plans “to work for the abolition of the board 'through legal and honorable methods.'”20

The suit against the PAB, brought by the Locust Club and seven officers (John Hunt, Bennie Jaskot, George Signor, Richard Sterling, Anthony D'Angelo, Nelson Evans, and Joseph Favata), argued that police named in cases before the PAB have “no adequate legal remedy against actions of the board.” Specifically, officers were “forced to testify against themselves” and had “no redress against decisions of the board even though the board is investigating charges which are legally defined as crimes,” according to a Times-Union article from April 16, 1965.21 The officers listed in the suit stated in court papers that “they are all subjects of complaints to the board” and because of this, they have been “'damaged in (their) professional ability to perform (their) jobs'.” The police were represented by attorney Thomas G. Presutti.

On April 27, Citizens for Abolition of the Police Advisory Board “won the right to intervene as a friend of the court” against the PAB, according to a Democrat & Chronicle article published on April 28.22 Supreme Court Justice Charles B. Brasser allowed the request and postponed the hearing till the following Tuesday. Justice Brasser didn't see “how anyone's interests will be seriously prejudiced if the [restraining] order stays in effect one more week.” June Weisberger, representing the city and the board, objected to the “intervention” by the civic group on the grounds that they were not legally aggrieved and that the restraining order issued by Justice Macken was entirely “too broad.” The justice rejected the motion to modify the order.

A week later, May 6, State Supreme Court Justice Jacob Ark modified the restraining order against the board. The order was limited to the “three patrolmen against whom complaints are pending before the board—John R. Hunt, Joseph J. Favata and Nelson T. Evans,” according to a Times-Union article from May 7.23 This ruling meant that the board could once again do its work beyond the cases of the three named officers above.

While the court gave Presutti, representing the police, till May 20 to file a brief and May 27 for Rosario J. Guglielmino, representing the board, before a date for oral arguments could be set regarding a motion for a temporary injunction, the Police Conference of New York, Inc. made headlines in the Democrat & Chronicle on May 18 with the promise of financial and moral support to the Locust Club and its legal battle with the board. The Police Conference claimed 50,000 members in New York State with aid coming not only from them, but a nation-wide federation of law enforcement officers.24

In late April, Lawrence Jost from Gates, wrote to the Democrat & Chronicle exposing CAPAB as nothing more than a group of mean-spirited police advocates who would use intimidation and harassment against people supportive of the board. Jost was heading to a picket held by CORE and other civil rights group outside the Policemen's Ball on April 24 when he was accosted by CAPAB members because he refused to take their literature: “I was met by two men passing out leaflets urging the abolition of the Police Advisory Board. After seeing what they were passing out, I returned the card and began to walk up the steps.” His civility was paid in kind by one of the men calling out, “Are you going up there with those slobs?” Then, as he was entering the building, he was approached by different members of CAPAB. When he refused their literature, one of the men said, “You mean that you're with the enemy out there, CORE?” In the letter to the editor, he goes onto to chastise the organization and its members for not upholding their own proclaimed values of honor and legality. About a week later, Lawrence C. Conway from Citizens for Abolition of the Police Advisory Board, responded to Jost's letter. Conway ate crow on behalf of his organization.25

That fall, the CAPAB notified “approximately 500 city policemen that the five Republican and five Conservative candidates for City Council have pledged they will work for abolition of the controversial board if they are elected,” according to an article from the Democrat & Chronicle from September 17.26 CAPAB seemingly wanted to maintain a media presence and both the Democrat & Chronicle and the Times-Union wanted to help if they could.

Then, on December 31, 1965, Supreme Court Justice Jacob Ark ruled on the suit brought against the Police Advisory Board. Specifically, he ruled that, “the right of the board to investigate and make recommendations must be eliminated,” according to a Times-Union article, and “those functions should be performed by the commissioner of public safety.” The justice limited the board's powers drastically to “receipt of complaints only.” 27

In the 10-page decision, Justice Ark explained his decision stating that, “[the commissioner] is in a better position to make a judgement as to what force was necessary under a given set of circumstances and whether the police officer was faced with a situation in which he had no time for calm reflection but acted reasonably under the exigency that confronted him.” Aside from calling upon police expertise to determine if an officer used excessive or unnecessary force, Justice Ark also criticized the city's position with regard to making cases public: “The board overlooks the fact that although its membership consists of nine highly respected members of the community when it it makes a public statement it does not speak for them as individuals, but with the authority of an official body of the City of Rochester. Its public criticism of a police officer bears the imprimatur of the City of Rochester.” This represented a “reprimand” which could only be given by the commissioner after a finding of guilt was made against the officer in question. He also made clear that the board's activities were intertwined with the operations of the police bureau and the Department of Public Safety violating “the rights of a police officer against whom a complaint was filed.” Thankfully, and astoundingly, the story doesn't end here. The city, in an extremely progressive move, pushed ahead.

The headline, “City to Fight Ruling on Police Board” announced the start of Act Two in the PAB saga. On January 6, 1966, City Manager Seymour Scher stated that an early appeal would be made to the Appellate Division, Fourth Department by Corporation Counsel John R. Garrity.28 That appeal wasn't presented for over a year.

The hearing took place on October 16, 1967, according to a Times-Union article from October 10, 1967. The appeal was, “argued before five judges of the Appellate Division, Fourth Department.” The article said that if the court reversed the decision, “it in effect would restore the Police Advisory Board's powers.”29

Representing the Locust Club on October 16 was Ronald J. Buttarazzi. The attorney for the police argued that there was an “irreconcilable conflict” between the city's charter and the PAB ordinance. According to Buttarazzi, the safety commissioner should have “exclusive control” over the discipling of police. His said the “underlying issue” is that officers can be accused and convicted of crimes by the board without a “judicial trial.” He also took issue with the fact that “unnecessary” and “excessive” were not defined.

Representing the City of Rochester on that Monday was Ruth B. Rosenberg. She argued that the overlapping of powers between the safety commissioner and the board was done intentionally. It was created for the purpose of providing an “alternative and objective forum” to process complaints against officers for excessive and unnecessary use of force. The Times-Union article this came from highlighted portions of Buttarazzi's statements and didn't include much else in the way of how the case was argued. After arguments were made, “the court reserved decision” on the ruling, which took months to come down.30

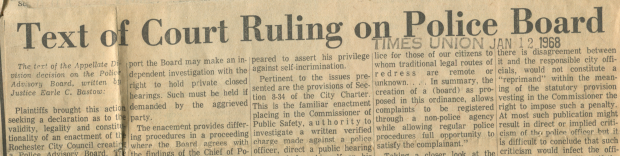

Nearly three months later, the Appellate Division handed down its decision. The text of the decision, written by Justice Earle C. Bastow, appeared in the Times-Union on January 12, 1968. Justice Bastow opened with the particulars of the suit brought against the board by the Locust Club and then proceeded to write, “A proper understanding of the issues presented requires examination of the provisions of the ordinance.” From here he described the City Charter, how the advisory board functioned and its powers. Then, in the middle of the text, Justice Bastow quotes Justice Ark's finding: “...the functions of the Board have actually become intertwined with the operation of the Department of Public Safety, and particularly the Police Bureau in violation of the rights of a police officer against whom a complaint was filed.” Justice Bastow wasted no further ink as he spoke for the majority: “We reach a contrary conclusion. ”

The justice affirmed that the legislated power to City Council establishing the advisory board was “valid.” He wrote, “In summary, the creation of a (board) as proposed in this ordinance, allows complaints to be registered through a non-police agency while allowing regular police procedures full opportunity to satisfy the complainant.” Justice Bastow went on to specifically cite sections of the ordinance in regards to disagreements between the board and city officials. He wrote, “In the absence of any disciplinary power vested in the Board it is difficult to imagine a 'recommendation' that could exceed one that upon the facts presented some affirmative action should be taken by the city administration. The result would be a plain difference of opinion between city officials and the Board.” The justices did not feel the “concern” expressed by the police that such a recommendation would stigmatize the named officer. Neither did they “share the view” that publicizing the recommendation “would constitute a reprimand that only the Commissioner may impose.” In fact, the justices found that the ordinance, “in no way diminishes, dilutes, or infringes upon the statutory power vested in the Commissioner” to punish officers who committed misconduct. “At most such publication might result in direct or implied criticism of the police officer but it is difficult to conclude that such criticism would infect the official record of the officer,” he wrote.

Justice Bastow went on to write about the how the ordinance was trying to strike a “balance between the rights of the police officer and the rights of the citizen.” He then quoted from the report recommending adoption of the board: “The board should contribute rather than impair, the efficiency of police performance of allowing grievances, some real, some imagined, to be considered by a responsible body of citizens, rather than remain, as they often do, smoldering embers of mistrust and contention between police and citizens.”

Near the end of the decision, Justice Bastow dismissed the argument that publicizing a recommendation against an officer is “sufficient reason to strike down the ordinance.” The justice then referenced some case law telling the complainants that police, like judges, “are forced to make unpopular decisions,” and that they are supposed to be “men of fortitude, able to thrive in a hardy climate.” Essentially, the justices told the police that criticism was a part of the job—deal with it. He then dismissed the “other contentions” raised by the police because he found them “without merit.” He concluded, “The order should be reversed and judgement entered declaring chapter 17 of the Code [which created the legislative power to establish the Police Advisory Board] valid and constitutional.”31

The day after the Appellate Division found the board “valid and constitutional” and more than two years after the board was stopped from doing its work by court injunction, the Democrats in control of the city started to backslide. According to Democratic County Chairman Charles T. Maloy, “'a lot things have happened since the board was established almost five years ago, and I think you have a different climate here now.'” Democratic Councilman Andrew G. Celli, said he “has had no complaints or demands for investigation.” Public Safety Commissioner Mark H. Tuohey said he “doesn't feel there is a need for an advisory board.” Meanwhile, the police were determining if they wanted to appeal the decision of the Appellate Division. The president for the Police Locust Club, Ralph Boryszewski, said “it will be up to the membership to determine if the case is taken to the Court of Appeals.”32

Which, of course, they did. In a Democrat & Chronicle article dated February 6, 1968, the Police Locust Club announced that it was “filing an appeal” with the highest court in the state based on a decision from the Appellate Division, Fourth Department “which upheld the advisory board as legal.” Papers were filed by Buttarazzi on behalf of the Locust Club.33

On April 4, the Court of Appeals granted a motion to stay in favor of the police. The PAB's activities were halted by the courts on the condition that the police union “present its case against the Police Advisory Board (PAB) during the week of April 15.” The PAB, which had begun its work on February 1 and reviewed 10 cases of police brutality, was abruptly ordered to cease its activity on April 4. The article reported that a decision could be handed down sometime between May and June of 1968.34

Then, on June 14, 1968, New York State's highest court, the Court of Appeals, voted 6-1 against the Locust Club, affirming the decision of the Appellate Division, Fourth Department, and once again finding the Police Advisory Board to be constitutional. Associate Judge John Scileppi wrote the only (dissenting) opinion as the majority wrote nothing. Judge Scileppi said he didn't even get to the issue of constitutionality because the ordinance, in his opinion, “is in direct conflict with . . . the Charter of the City of Rochester . . . and 'therefore, invalid.'”35 And so we enter the final act of the saga.

The police union announced a few days later on June 16 in a Democrat & Chronicle article that it hoped to take the “case before the U.S. Supreme Court.” President Boryszewski told the paper that the club would have a special meeting to vote on whether or not to take the case to the highest court in the land. At the very least, the president said, he would “bring the police advisory board issue before the International Police Conference” the following month. He claimed the Court of Appeals ruling was “another step taken by this body to diminish further the power of the grand jury.” He called fellow officers a “minority of citizens” that were “restricted and denied the protection of the 14th Amendment.” He said the court's ruling, “opens the door for all cities to have this kind of board.”36

In an obvious move to protect a “minority of citizens,” on December 10, 1968, the Times-Union reported that the Locust Club had moved ahead and filed papers with the United States Supreme Court. The police were represented by Ronald J. Buttarazzi. The article laid out five points of argument brought before the court, although there were 10 all together: 1) “punishment [sic] might be imposed without trial of [sic] other due process of law,” 2) “the board [sic] may determine whether a man is a criminal without the right of an individual to confront his accusers,” 3) “it violates [sic] the Fifth Amendment in that a policeman can be forced to testify against himself or risk the loss of good name and public job,” 4) “it authorizes [sic] 'cruel and unusual punishment,' outlawed by the Eighth Amendment,” and 5) “it denies [sic] to policemen equal protection of the law granted all other citizens.” The article also stated that the board had “not been functioning because resignations have left it without a quorum.” At that time, there were only five members on the board. Quorum required six. Complaints, according to the board's executive director Rosario J. Guglielmino, “have been received and processed.”37

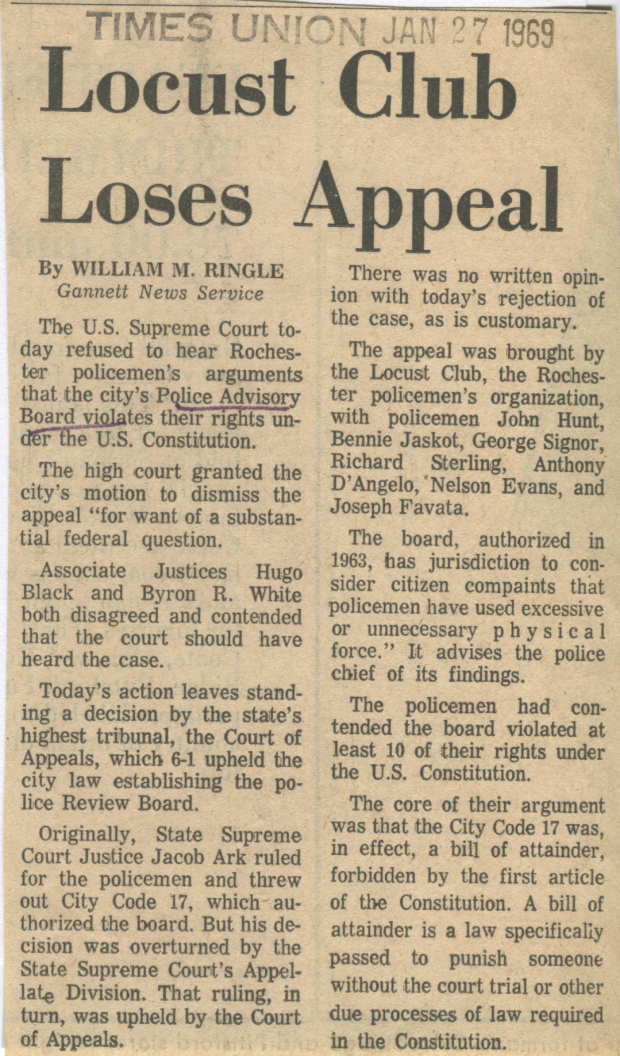

Nearly two months later, the legal saga of the Police Advisory Board ended. The U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear the Locust Club's case and accepted the city's motion to dismiss the case “for want of a substantial federal question.” No opinion was written regarding the dismissal, a common practice, though Associate Judges Hugo Black and Byron R. White said “the court should have heard the case.” The action of the court left standing the New York State Court of Appeals decision that “upheld the city law establishing the police Review Board [sic].”38

With the board finally found constitutional by the Appellate Court, the Court of Appeals, and the U.S. Supreme Court, the issue of the board went back to the local government for action. And there it sat with little action taken. On June 12, 1969, the American Civil Liberties Union filed a suit against the city on behalf of two board members and two people waiting to make complaints to the board for “excessive force.” The city had no comment.39

A little over a month later, the suit was dropped. Apparently, through some confusion, it was figured out that there were seven members on the board, not five as previously thought. According to a Democrat & Chronicle article, one member of the board verbally resigned, but not formally and in-writing. Another member was “on sabbatical leave” but returned.40

It didn't matter though. With Mayor-elect Stephen May, a Republican, moving into office, the die was cast regarding the PAB. The Democrat & Chronicle ran an article in December of 1969 asking the mayor-elect what would happen to the PAB. “We haven't discussed it in any detail for a long time,” said May. “It will be one of a number of policy questions the administration will be come to grips with when it is firmly established.” The article also noted that the board was under quorum again as James S. Malley requested that he not be reappointed. The outgoing Democratic Party administration “failed to reappoint persons to fill the vacancies, despite requests by remaining board members that it do so.” Republicans, the paper noted, had been “traditionally against such review boards.”41

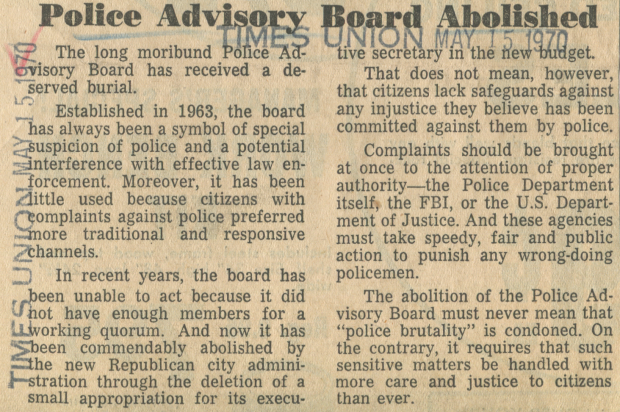

Finally, in an article from the Times-Union dated May 14, 1970, it was announced that the Police Advisory Board was abolished: “The Republican City administration has decided to bury the Police Advisory Board which, for all practical purposes, has been dead for sometime.” The paper noted that neither the outgoing “Democratic city manager, nor the new Republican administration, appointed members to make it active again.” As an aside, it was also noted that with the abolition of the board, the executive director would no longer receive an annual salary which, would mean “a savings to the city of $5,000.”42 The abolition of the board was seen as “commendable” by the Times-Union in another article the following day.43

Why does this history matter? In the history of the City of Rochester rarely does such progressive legislation get passed. The legislation that created the Police Advisory Board actually created some transparency within the police department and some level of public accountability for of ficers and their actions if the board and the chief of police could not come to an agreement. It was not a perfect system by any means. However, today, this history is long dormant and doesn't even scratch the surface of the news when the issues of police accountability and police violence come up in the community. We must always be skeptical of power when—in this case the City Council, the mayor, the police and their union— firmly adhere to and support, as Howard Eagle called it in the 1990s, a “toothless tiger” structure of accountability—the Civilian Review Board now in operation. The current board does not have subpoena power, independent investigative power, and disciplinary power. Without these three powers, any type of accountability structure is doomed from the start—though in the PAB's case, its independent investigative power as well as its ability to publicize the wrongs of named officers publicly, scared the hell out of the police and their union. The current Civilian Review Board has failed the people, while supporting corruption, brutality, murder, and misconduct at all levels in the police chain of command. The call for an independent civilian review board has been on the table for over 50 years and each time it comes up, the City Council, the mayor, the police and their union, bat it down because they know that it would be a real step toward justice and community/civilian control of our, as Adam McFadden said a few years ago, “out of control” police force.44

_________________________

1Rochester History XXV, 4, “A History of the Police of Rochester, New York.” (October 1963), p. 25 (http://www.rochester.lib.ny.us/~rochhist/v25_1963/v25i4.pdf).

2 Ibid. P. 25.

3 Ibid. P. 25.

4 See a scan of the 1963 Police Advisory Board legislation as well as comments submitted to Rochester City Council for and against it, in .pdf format at: http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146813 & http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146877.

5 Spezzano, Vince. 1963. “9-Man Police Advisory Board Named.” Times-Union, May 20 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146822).

6 Gordon, David. 1968. “'Facts on Board Ignored'.” [Letter to the Editor] Democrat & Chronicle, February 6 ().

7 Spezzano, Vince. 1963. “Police Petitions Against Board Get 40,000 Names.” Times-Union, March 12 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146824).

8 DeCarolis Trucking and Rental Co., Inc. President Louis J. DeCarolis, Peter V. Ereg, and Russell B. Sanguedolce. 1963. Full-page advertisement. Democrat & Chronicle, March 10 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146875).

9 No author listed. 1963. “Police Unit In 1st Ruling.” Times-Union, July 18 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146823).

10 See both of these articles. No author listed. 1964. "Year's Score: 2 Cases for Police Board." Times-Union, August 7 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146865). No author listed. 1964. “'Business' Slow for Police Board.” Democrat & Chronicle, August 8 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146866).

11 Vogler, Bill. 1965. “Cases Rising, Police Review Board Reports.” Democrat & Chronicle, October 19 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146867).

12 No author listed. 1968. "10 Cases Reviewed By PAB." Democrat & Chronicle, February 2 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146868).

13 No author listed. 1965. "Advisory Board Denies Cops Used 'Extra Force'.” Democrat & Chronicle, October 12 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146870).

14 No author listed. 1964. "Year's Score: 2 Cases for Police Board." Times-Union, August 7 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146865).

15 No author listed. 1965. "Advisory Board Denies Cops Used 'Extra Force'.” Democrat & Chronicle, October 12 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146870).

16 No author listed. 1965. "Officials Critical of Police Probe." Times-Union, June 4 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146869).

17 No author listed. 1965. "Complaint Put Into Cops' Files." Democrat & Chronicle, June 4 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146871).

18 Editorials, letters to the editor and some articles from the Times-Union newspaper critical of the Police Advisory Board 1963 – 1965: "Does Police Board Need Executive Staff?," June 25, 1963 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146880); "City Must Answer FBI On Police Board Charges," October 1, 1964 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146882); "Would Abandon Police Board," August 14, 1964 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146893); "Police Board Opposed," August 12, 1964 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146894); "Lauds Police Board Criticism," October 1, 1964 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146896); "Police Advisory Board Should Be Abolished," January 11, 1965, "Police Board Hurts Crime Fight," January 15, 1965, "Feels Advisory Board Hampers Police," January 22, 1965, and "Raps Police Review Board," January 25, 1965 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146898); "Urges Elimination Of Police board," February 10, 1965, and "'Get Advisory Board Off Us,'" February 24, 1965 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146899); "Police Need Full Support To Help the War Against Crime," March 13, 1965, "Abolish Police Board," March 17, 1965, "Good Question," March 22, 1965, and "Calls for Abolishing Police Advisory Board," March 26, 1965 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146900); "Citizens Group Hits Police Board," April 2, 1965, "Sibley Unconvincing On Need for Police Board," April 12, 1965, and "Review Board Is a 'Group Libel'," April 27, 1965 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146901); "'Disband Police Board As Soon as Possible'," May 18, 1965 and "Police Board--No Confidence," May 27, 1965 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146906); "Supports Abolition Of Police Review Board," June 5, 1965, "Police Board 'Fundamentally Unfair'," June 5, 1965, and "Abolish Police Advisory Board," June 10, 1965 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146910); "'Time To Put End'," July 1, 1965 and "Ex-N.Y. Police Boss Is Still Bristling," July 21, 1965 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146911); "Strong New View on Police Board," September 22, 1965 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146914); "Police Board Opponents Get Their Lumps But Deserve Credit," October 2, 1965, "Comment on Bishop's Statement" and "Urges Abolishing Police Review Board," October 4, 1965, and "Police Boards Criticized," October 23, 1965 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146915); and "'Dump Police Review Board'," December 31, 1965 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146916).

Editorials, letters to the editor, some articles, and an advertisement from the Democrat & Chronicle newspaper critical of the Police Advisory Board 1963 – 1965: DeCarolis, Ereg, & Sanguedolce take out full-page ad against PAB, March 10, 1963 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146875); "Police Board's Work is Done," January 11, 1965 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146919); "'Advisory Board Unnecessary'," February 9, 1965 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146921); "'Advisory Board Should Go'," March 25, 1965 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146922); "'People Should Vote On Advisory Board'," April 22, 1965 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146923); "'City Doesn't Need Advisory Board'," May 2, 1965, "'Advisory Board Belittles Cops'," May 4, 1965, "'Police Board Foes Lacked Courtesy'," May 4, 1965, "Board Opponent Makes Apology," May 12, 1965, and "N.Y. Top Cop Quits Over Review Issue," May 19, 1965 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146924); "10 Vow to Fight Advisory Board," September 17, 1965 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146925); and finally, "All Police Advisory Boards Hit As 'Forced by Minorities'," October 23, 1965 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146926). It should be noted that the Democrat & Chronicle in 1964 focused a lot of their reporting on the possibility of a police review board in New York City.

19 No author listed. 1965. "Police Suit Fights Advisory Board.” Times-Union, April 16 ().

20 No author listed. 1965. "Group Will Fight Advisory Board.” Democrat & Chronicle, March 27 ().

21 No author listed. 1965. "Police Suit Fights Advisory Board.” Times-Union, April 16 ().

22 No author listed. 1965. "Citizens Group Role OK'd In Police Board Suit.” Democrat & Chronicle, April 28 (); No author listed. 1965. "Intervention Allowed in Board Suit.” Times-Union, April 28 ().

23 No author listed. 1965. "Police Board Curb Modified by Court.” Times-Union, May 7 ().

24 No author listed. 1965. "Lawmen Pledge Funds To Fight Advisory Board.” Democrat & Chronicle, May 18 ().

25 Jost, Lawrence. 1965. "Police Board Foes Lacked Courtesy.” [Letter to the Editor.] Democrat & Chronicle, September 17 and Conway, Lawrence C. 1965. “Board Opponent Makes Apology.” [Letter to the Editor.] Democrat & Chronicle, May 12 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146924).

26 No author listed. 1965. "10 Vow to Fight Advisory Board.” Democrat & Chronicle, September 17 (http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/146925).

27 Hoch, Earl B. 1965. “Police Advisory Board Curtailed By Court Ruling.” Times-Union, December 31 (). What's interesting about this date, is that the Democrat & Chronicle continually said the ruling happened on December 31, 1965 and the Times-Union, initially said December 30, 1965, but eventually switched it to the 31.

28 No author listed. 1966. "City to Fight Ruling on Police Board.” Democrat & Chronicle, January 7 ().

29 Boczkiewicz, Robert. 1967. "Police Advisory Case to Revive.” Democrat & Chronicle, October 10 () and No author listed. 1967. "Appellate Division Slates Hearing on Police Board.” Democrat & Chronicle, October 11 ().

30 Taub, Peter B. 1967. "Police Board Plea Aired.” Democrat & Chronicle, October 16 ().

31 Bastow, Earle C. 1968. "Text of Court Ruling on Police Board.” Times-Union, January 12 ().

32 No author listed. 1968. "Council Now Appears Cool.” Democrat & Chronicle, January 13 ().

33 Stearns, Anne. 1968. "Advisory Unit Case Appealed.” Democrat & Chronicle, February 6 ().

34 Gannett News Service. 1968. "Court Stalls Board.” Democrat & Chronicle, April 5 ().

35 O'Brien, Emmet N. 1968. "Local Police Board Gets OK from Court.” Democrat & Chronicle, June 15 ().

36 No author listed. 1968. "Police Advisory Board May Face New Appeal.” Democrat & Chronicle, June 16 ().

37 No author listed. 1968. "Rights Periled, Police Say; Asking Top Court Hearing.” Times-Union, December 10 () and Ringle, William. 1968. “Supreme Court Gets Advisory Board Issue.” Democrat & Chronicle, December 10 ().

38 Ringle, William. 1969. “Locust Club Loses Appeal.” Democrat & Chronicle, January 27 ().

39 Nauer, Mike. 1969. “Board Revival Sought.” Democrat & Chronicle, June 13 ().

40 No author listed. 1969. “Police Panel Suit Dropped.” Democrat & Chronicle, July 17 ().

41 No author listed. 1969. “Police Board Fate in Doubt Under GOP.” Democrat & Chronicle, December 30 ().

42 No author listed. 1970. “It's Official: Advisory Panel Buried.” Times-Union, May 14 ().

43 No author listed. 1970. “Police Advisory Board Abolished.” Times-Union, May 15 ().