InfoDoc on Rochester's failed Body Worn Camera draft policy

Primary tabs

Below is a PDF of the BWC [Body Worn Camera] Manual Draft 4.29.2016 Public Release found as a link on the Rochester Police Department website concerning the Rochester Police Department's (RPD) development of policies for the use of body worn cameras. This is not the final policy, but it seems like it could be headed that way, if the public does not get involved.

Link to a PDF download of the final manual (hint, very few changes from the first one): www.cityofrochester.gov/WorkArea/linkit.aspx?LinkIdentifier=id&ItemID=85...

The many failures of the draft policy for Body Worn Cameras

Scroll down for more information on 10 failures of the draft policy released by the Rochester Police Department regarding the use of Body Worn Cameras (BWCs). Rochester Indymedia encourages you to read the policy and compare our concerns with the policy as written. We are aware that there are additional concerns and failures with the draft policy, but these 10 seemed to be most egregious. Check back here for future updates!

Failure #1: Should officers deviate from any of the policies listed, there is NO presumption of guilt and NO consequence for violating policy. We must demand officer accountability! We must demand a presumption of guilt for violating policy as well as discipline be incorporated into the policy!

There are no consequence listed in the draft policy for violating its directives and no presumption of guilt for deviating from the BWC policy.

What does "no consequences" mean? It means exactly what it sounds like: for violating any portion of the proposed draft policy regarding BWCs, there are zero consequences, zero penalties, and no accountability for individual officers and supervisors.

The policy fails to include a section on discipline and what constitutes a violation. Theoretically, if an officer violates the policy, then there could be disciplinary consequences. It is vital that the final BWC policy include this section. Stating that discipline "will be administered" isn't good enough. The policy should elucidate specific types of discipline. For example, for a first violation, the officer would receive a reprimand. On the second offense, the officer would be suspended for 30 days. And on the third violation, the officer would be fired. Currently, with the way the policy is written, police impunity is built-in, with no accountability offered.

What does "presumption of guilt" mean? If an officer violates the policy, for example, by not turning the camera on or by turning it off, we presume that the officer is guilty of a violation. If we are demanding police accountability, then a presumption of guilt would hang over that officer and their BWC footage. If an officer didn't turn the camera on, in violation of BWC policy, then at trial the jury would be unable to review the footage and any (allowed) testimony from officer would be treated as highly suspect.

Both officer discipline and the presumption of guilt for violating BWC policy are crucial if there is to be any accountability for police officers operating with BWCs. We must demand that the presumption of guilt and specific officer discipline with a clear definition of what a violation of policy means, be built into the policy.

Failure #2: Officers have discretion to turn the cameras on and off. (Including your private residence!) We must demand that the cameras be always on or that individual officers cannot have control!

According to the BWC draft policy[1], "members assigned a BWC will activate it and record all activities..." which means that the individual officers will have the power to turn the cameras on and off at their discretion. This leaves a wide margin of potential abuse for officers who may be operating in an illegal or abusive manner. Again and again, Rochester Indymedia has heard from people that the cameras must remain on all the time, or at the very least, individual officers must not have the ability to turn the cameras on and off.

There's also the issue of police discretion when BWCs are on in private residences. There is no mention of what is and is not permitted to be filmed inside a private residence, where individual privacy rights are very different from street or public interactions. Assuming that the cameras have to remain on, if the officer did not get consent to record, on film, within a private residence, then the footage would be deleted or, at least, it would be inadmissible in court.

We must demand that the cameras remain on all the time or that the individual officers have no ability to turn the camera on and off.

Failure #3: Police conducting investigations into police misconduct are prohibited from using their body cameras. We must demand that police turn the cameras on for both civilian and police investigations!

The BWC draft policy[2] notes that officers are required to have their cameras on during calls for service or self-initiated interactions with civilians, enforcement activity, Quality of Service Inquiries, pursuit driving, foot pursuits, prisoner transports, when in proximity to a prisoner, certain identification procedures, searches and seizures, traffic stops, vehicle checkpoints, and civilian transports. These are all civilian interactions with officers.

However, when it comes to investigatory action into police misconduct conducted by the internal affairs section of the department, Professional Standards Section, the BWC draft policy[3], states, "Members will not record with BWCs interviews relating to departmental investigations being conducted by PSS or by any other section performing similar functions."

In the case of civilian criminal matters, police have full discretion to use BWCs. In fact, in many interactions with the public they are required, according to the draft BWC policy[4], to turn their cameras on. That requirement ends as soon as an investigation is focused on police misconduct. If we value integrity and fairness, two terms PSS loves to talk about, then it is imperative that BWCs be turned on during police investigations into police misconduct. We must demand that the cameras stay on when criminal investigations are occurring–regardless of whether they civilian or police in nature. No exceptions.

Failure #4: BWCs are in the off position unless otherwise ordered when the SWAT Team, Bomb Squad, and Crisis Negotiation Team are deployed. We must demand that the cameras be on when these "Special Teams" are deployed!

If the above listed units are called to specific situations, according to the BWC draft policy[5], these teams "will not record with a BWC" unless "authorized by the Chief of Police, a Deputy Chief, Division Commander, or the Team Commander."

Let's start with the SWAT team, part of the "Special Teams" mentioned above. The Special Weapons and Tactics (SWAT) team[6] is charged with responding to "hostage incidents, barricaded armed subjects, high-risk warrant service, high risk suspect apprehension, protection of dignitaries, and any other situations as determined by the Chief of Police" and other high ranking officers in the department.

Their duties also include evicting grandmothers and families–such as Catherine Lennon–from their homes under fraudulent orders from bailed out banks and conducting botched drug raids based on bad intelligence that lead to the killing of innocent people. Lives–along with homes and personal property–are destroyed with no reparations to the victims of this militarized, police violence.

Concerning drug raids, it's worth quoting Michelle Alexander in full, from her book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, regarding the rise of SWAT teams and their primary use since the 1980s (pages 74 and 75):

SWAT teams originated in the 1960s and gradually became more common in the 1970s, but until the drug war, they were used rarely, primarily for extraordinary emergency situations such as hostage takings, hijackings, or prison escapes. That changes in the 1980s, when local law enforcement agencies suddenly had access to cash and military equipment specifically for the purpose of conducting drug raids.

Today, the most common use of SWAT teams is to serve narcotics warrants, usually with forced, unannounced entry into the home. In fact, in some jurisdictions drug warrants are served only [sic] by SWAT teams–regardless of the nature of the alleged drug crime. As the Miami Herald reported in 2002, "Police say they want [SWAT teams] in case of a hostage situation or a Columbine-type incident, but in practice the teams are used mainly to serve search warrants on suspected drug dealers. Some of these searches yield as little as a few grams of cocaine or marijuana."

The rate of increase in the use of SWAT teams has been astonishing. In 1972, there were just a few hundred paramilitary drug raids per year in the United States. By the end of the 1980s, there were three thousand annual SWAT deployments, by 1996 there were thirty thousand, and by 2001 there were forty thousand. The escalation of military force was quite dramatic in cities throughout the United States. In the city of Minneapolis, Minnesota, for example, its SWAT team was deployed on no-knock warrants thirty-five times in 1986, but in 1996 that same team was deployed for drug raids more than seven hundred times.

These encounters, Alexander notes, "are not polite encounters." Police conduct raids in the middle of the night or in the early morning hours by blasting into homes, "throwing grenades, shouting and pointing guns and rifles at anyone inside, often including young children." She continued that in recent years, "dozens of people have been killed by police in the course of these raids, including elderly grandparents and those who are completely innocent of any crime."

Lydia Boston and her young children were traumatized in a drug raid based on bad intelligence in 2011

When the SWAT team is deployed, we must demand that BWCs be on. The targets of these raids must have access to BWC footage to be used as evidence in civil and criminal suits brought against the department, especially when things go wrong.

With regard to the Bomb Squad and the Crisis Negotiation Team, these "Special Teams" often work in tandem with the SWAT team and should not be exempted from having their cameras on as the default setting. In fact, under General Order 630[7], the SWAT team must "maintain close working relationships with specialized teams (e.g., the Crisis Negotiation Team (CNT), the K-9 Unit and the Bomb Squad)" as well as conduct joint training exercises at least once a year. Regardless of whether those other "Special Teams" are working with the SWAT team, the cameras must be on.

Let's assume that the cameras are in the default on position; if a supervisor orders the cameras off, then the burden of proof would be on the police to show why turning the cameras off was imperative–and if it can't be shown why the cameras had to be turned off, then the presumption of guilt rests with the individual officers and their supervisors, not the victims of police action.

For the reasons stated above, we must demand that the cameras are in the default on position when any of the "Special Teams" are deployed.

Failure #5: BWCs are in the off position unless otherwise ordered when the Mobile Field Force (MFF), another assault unit of the RPD, is deployed to protests, demonstrations, and areas of civil disorder. We must demand that the cameras be on when the MFF is deployed!

The Mobile Field Force (MFF) is a beast unto itself. If the MFF and / or the Grenadier team is deployed, according to the BWC draft policy[8], these teams "will record with assigned BWCs" as "directed by a supervisor and/or in accordance with an operational directive." Again, the camera is in the default off position unless the officers are directed otherwise.

Rochester Police Department General Order 605[9] defines the MFF force as, "a specially trained group personnel assigned to provide rapid, organized, and disciplined response to civil disorder, crowd control, or other tactical situations."

Aside from the problem of police determining the definitions of "civil disorder," "crowd control," and "other tactical situations," protected First Amendment activities such as protests and demonstrations–where the likelihood of police violence is high–the cameras must be in the default on mode. Otherwise, you get situations like the police riot against anti-war protesters on the Main Street bridge in 2009 where police claimed they had to intervene violently because protesters blocked a fire truck. Video evidence was offered contrary to the police lie, but the mainstream news agencies refused to report on the truth of the matter.

The policing of First Amendment activities–by such heavily armed police–where body cameras are in the default off position, is an invitation for abuse of power and brutality. In all of the above situations, we demand that the cameras must be in the default on position.

Failure #6: Officers are allowed to review their own footage when writing their reports–a potentially abusive situation. We must demand that officers not be allowed to review their own footage when preparing reports!

According to the BWC draft policy[10], members can view their BWC recordings "if available" in order to "assist in accurate reporting." Police generally write their reports hours or days after the incident. Each time someone recalls a memory, it changes a little. Memory recall isn't perfect.

In the BWC draft policy[11], under the section about officers having access to footage while writing their reports, the policy notes, "the purpose of using BWC recordings in writing reports is to maximize the accuracy of the report—not to replace the member’s independent recollection and perception of an event." Except that while the police want us to take their word on this, the reality doesn't bear fruit.

With the acknowledgement that recall isn't 100% dependable, reports are more accurate the closer in time they are written to the actual event. The problem with having officers review video as they write their reports–up to 24 hours or more after the incident–is that the review of the video corrupts their memory and their brains start to work out narratives of what happened in relation to what the video shows rather than what they recall (and did) without the aid of the video.

In abusive situations, officers might engage in misconduct and intentionally rewrite their reports to reflect that misconduct in a more favorable light–obfuscating the truth in the process.

In one national case, that of Laquan McDonald, police claimed in initial reports that Mr. McDonald was going down Pulaski Road stabbing car tires with a knife. According to the Chicago Tribune article linked above, Fraternal Order of Police spokesperson Pat Camden claimed that the teenager had a blank, "100-yard stare" and that he was non-responsive to police orders after allegedly damaging a police cruiser.

Mr. McDonald then "lunged at police, and one of the officers opened fire," according to police. The truth of these statements came out a year later after a line officer informed Jamie Kalven, an investigative journalist, of hidden and nondisclosed footage. Mr. Kalven pushed and pushed with other activists and family members until the police and the city were compelled by a judge to release the footage.

Contrary to police narratives and official reports, Mr. McDonald did not lunge at cops–he was walking calmly away from them with his hands at his sides. The 17-year-old Black teenager was then gunned down by Chicago Police Department officer Jason Van Dyke with 16 bullets–many of them entering his body after he was wounded and on the ground.

It's cases like Mr. McDonald's that make the public skeptical of police having access to their own footage. Granted, the cover-up began immediately after Mr. McDonald's murder (with police going to a nearby Burger King and deleting some 86 minutes of footage from the chain's security system) and not during the writing of reports, but in the end, the false narrative and police reports all conspired against what really happened that night.

Locally, people have been arrested and held in the backseats of patrol cars, while officers conspired to come up with a favorable police narrative of what happened as well as determining charges for the arrestees. Some examples of this include the arrest of Willie Joe Lightfoot, the arrests of several anti-war demonstrators after a police riot in 2009, and the police union releasing false statements after the DA withdrew charges against Emily Good who was video taping a racially motivated traffic stop in front of her home on Aldine Street and was arrested for doing so by Mario "Cowboy" Masic.

Is there a compromise position on this? The Washington Post published an article describing a compromise position: officers write an initial report before viewing the video and then write a follow-up report after viewing the video where the officer would "acknowledge and attempt to explain any discrepancies between the video and the initial report." The second report would be used in court. This is an interesting compromise and certainly not what the BWC draft policy is advocating for here in Rochester. The cops want full access to BWC footage while they write their reports. We must demand that officers have no access to the videos on their BWCs. The temptation for abuse is too great.

Failure #7: The draft policy gives the District Attorney redacting power and direct access to BWC footage; all other lawyers must go through a longer, slower process! We must demand that the same process be used for all lawyers or remove the special access granted to the DA!

The BWC draft policy[12] contains a streamlined process for the District Attorney (DA) to have direct access to all BWC footage in addition to redacting power. Under Subsection A, number 1, the policy states that the City's Information Technology department and the Research and Evaluation Section (R&E) of the RPD will "provide direct access to MCDA [Monroe County District Attorney] to obtain BWC recordings stored in RPD's BWC System needed for criminal prosecution."

The draft policy goes on to state that the "MCDA will directly provide defendants with copies of BWC recordings," and here's the kicker, "as it [the DA] deems necessary." The term "necessary" is never defined. This creates a problem wherein the DA could know of certain footage but refuse to hand it over as the DA deems it not necessary–when in fact, it might be very necessary.

A third point in the process is that the DA "will be responsible for any required redactions" that the DA "provides to defendants." The terms "required" and "redactions" are not defined nor is there any process or standard of what would be "required" to be blacked out or fuzzed out–redacted–in these videos. An amazing amount of disproportional power is vested with the DA and the policy doesn't even define the terms of the power it is granting to the DA.

Redacting raises all kinds of questions: How does redaction work? Will it include facial blurring, voice scrambling, omitting sections of video entirely? Does redacting change the original footage or will an unredacted copy also be kept? What will be redacted and under what circumstances? Who is R&E and / or the RPD will have the responsibility to redact? If the DA and the Public Defender are given authority to redact, what guidelines for redaction will they be using and who will be responsible for ensuring redaction happens accurately and fairly? Who will have access to unredacted footage? For how long? And where will it be stored? The draft policy offers no answers to the questions above. Redaction doesn't promote transparency or accountability, but rather state secrecy.

Finally, the last step of the process states that the R&E section of the police department will be at the disposal of the DA as needed to "ensure necessary BWC recordings are obtained" by the DA. Basically, the police section that works on the BWC system is at the disposal of the DA when it comes to tracking down BWC footage.

If we scroll down the BWC draft policy[13] to subsection C, Defense Subpoenas or Demands in Criminal Cases, we very clearly see a different and more scrutinized process.

Instead of the above process, all defense subpoenas or demands in criminal proceedings by lawyers outside of the DA's office for BWC footage would go to the R&E section. They, in turn, would consult with the city's law department and the "appropriate prosecuting office" regarding the request. From there, R&E would identify the BWC footage that related to the demand or subpoena. Once the footage is identified, R&E would send copies of the requested footage to the defense attorney or office as "advised by the City Law Department and / or the prosecuting office." However, before any such copies are turned over to the defense, R&E will consult with the city's law department as well as the prosecuting office to "determine if any redactions may be required." R&E would follow their "legal guidance" concerning redacting. Finally, any copied BWC footage that was sent to the defense would also be sent to the "appropriate prosecuting office."

Again, the terms "redacting" and "required" are never defined. And again, any demands or subpoenas for BWC footage would go through the DA's or prosecuting attorney's office. Any "required redactions" would be made before the defense would be sent a copy of the footage and it appears that the defense attorney or office has no recourse to challenge any of the, as of now, undefined "required redactions." The other piece that is missing from this process is a time table: how long does each step take and when can the defense expect to get copies of footage? Will the defense get an unredacted version of the video? Without the above failures resolved, the power is solely held in the hands of the state with no recourse should a subpoena or demand be denied.

That's why we must demand that the process for obtaining BWC footage be the same for both the DA and all lawyers, or that there be no special, streamlined process for the DA's office.

Failure #8: The draft policy continually uses broad and undefined terms like "safe" and "practical." We must demand that this language be struck from the policy or that such language is clearly defined and accompanied by examples and guidelines.

The first instance of the terms "safe" and "practical" can be found on page 5 of the draft policy[14]. "Safe" and "practical" are not legally defined terms and are not defined in the draft policy. What do these terms mean? What constitutes "safe and practical"? Officer safety is already prioritized in civilian-police interactions. "Practical" is a broad term that can be a synonym for "convenient." These terms should not be used as the standard for officers' discretion in operating the BWCs and following procedures. The language potentially allows officers to use unbridled discretion for a number of other factors that amounts to officer choice about when cameras are on or off.

Therefore, we must demand that this language be struck from the policy, or, that such language is clearly defined and accompanied by examples and guidelines.

Failure #9: There is no outlined process for auditing the BWC project to make sure that it is in compliance. We must demand that the BWC policy include a section regarding audits as well as discipline for deviations of policy and that a civilian third party–with no connections to law enforcement–be responsible for running audits of the entire project.

The maintenance of the BWC project is complicated and involves many parties, including each individual officer who tags and enters their own BWC footage. According to the draft policy[15], there are 10 different tags or categories for officers to label their footage. There is no specific procedure or process in the draft policy for how audits of tagging footage are conducted. We must demand that a civilian third party–with no connections to law enforcement–conducts regular audits of tagged footage to ensure compliance with policy. Or, at the very least, R&E could do the tagging audits as long as a clear process is outlined and disciplinary action exists for deviation and abuse.

We know that the Civilian Review Board (CRB) is simply a rubber-stamping mechanism for police action with no actual power over police. We also know that the CRB is outsourced to a nonprofit organization–Center for Dispute Settlement–that gets paid directly from the RPD's budget to administer the CRB. Setting up a system where police have an undue amount of influence over the proceedings–an audit system in the case of BWCs–is the creation of yet another intentionally failed system. Police cannot police themselves. It is vital to have regular, independent audits where the auditors have no connection with any local, state, or federal law enforcement agencies.

Additionally, the same civilian third party would conduct a biannual audit of the whole project to ensure that it is performing as intended. We must demand that this be written into the final policy.

Failure #10: New York Civil Rights Law Section 50-a can be used by the RPD to block disclosure of BWC footage to the public using the Freedom Of Information Law (FOIL). We must demand that the city and police explicitly state in the policy that section 50-a will not be used to deny transparency.

The BWC draft policy[16] contains a list of exemptions to the Freedom of Information Law (FOIL). While section 50-a of the New York Civil Rights Law is not directly invoked, the first point states that FOIL requests can be "specifically exempted from disclosure by state or federal statute," which, is in effect saying that any public request for BWC footage could be denied under section 50-a.

According to the 2014 Annual Report from the Committee On Open Government (COOG), section 50-a is "an exemption from the ordinary rules of disclosure that apply to other government agencies. Section 50-a permits law enforcement officers to refuse to disclose 'personnel records used to evaluate performance toward continued employment or promotion.'"

The law was passed in 1976 and over the last 20 years, the exemption has broadened considerably. Again, according to the 2014 COOG report, the "narrow exception has been expanded in the courts to allow police departments to withhold from the public virtually any record that contains any information that could conceivably be used to evaluate the performance of a police officer. That means information about what an officer actually has done can be kept from the public in most cases. And it is."

Robert Freeman, executive director of the Committee On Open Government, discusses FOIL and 50-a at an Enough Is Enough event

The 2015 annual report elucidates how the section 50-a jeopardizes any attempt at police transparency in New York with the use of BWC footage: "Under current application of §50-a, many law enforcement agencies would surely contend that a recording can, in the words of §50-a, be 'used to evaluate performance toward continued employment or promotion' and, therefore, is exempt from disclosure." Thus, "if there is no public disclosure, a primary purpose of the bodycam would be defeated."

But wait, that's not all! Not only is there protection for police from disclosure of BWC footage (if they want to invoke section 50-a), but according to the draft policy[17] if there is an ongoing criminal investigation and a FOIL request asks for footage relating to that investigation, the chief has final, arbitrary authority over whether or not that footage will be released, regardless of differences in internal legal opinion between the city, the police department, and the prosecution.

We must demand that the city and police explicitly state in the final policy that section 50-a will not be used to deny transparency to the public.

Establishing transparency and improving police-community relations

In order to get $600,000 in federal BWC grant money, the city had to submit a Project Charter (see below), one of many documents. Section II, Background of the charter contextualizes why the city of Rochester needed federal funds for BWCs:

In an effort to provide a more accurate record of police encounters, foster the improvement of police-community relations, establish transparency, and improve the quality of evidence brought into criminal prosecutions, many law enforcement agencies across the country have begun to outfit their uniformed officers with body worn cameras. In accordance with this trend, the City of Rochester Police Department has undertaken a Body Worn Camera project.

If the above statement is a true rationale for why the city wanted BWC grant money, then the draft policy governing the use of the cameras is a complete contradiction. The draft policy doesn't mention transparency or police-community relations at all. And why should it? It is clearly written from a police point of view, where cameras are seen as another tool in their vast arsenal to use against people. Transparency was never the motivation.

To be honest, the city of Rochester was focused on getting BWCs regardless of whether there were policies or not. The question wasn't was the city getting cameras–we knew they were coming. The question was what policies would govern them. The above list indicates many failures of the current draft policy instructing officers on how to use BWCs. If the final policy is to reflect transparency and accountability, which will bring with it more trust, then it is incumbent on the people of Rochester to compel the police department, the police union, city council, and the mayor to make the required changes. If no changes are made, then a next possible step might be to demand the scrapping of the BWC project. We have an opportunity to make a democratic decision that will expand police transparency and accountability. Let's use it to create the best possible policy to serve the interests of the whole community, not just the police.

Project Charter for BWC project

Endnotes:

[1]: BWC draft policy, page 5, Section IV, Recording Requirements and Restrictions, subsection A, Mandatory BWC Recording

[2]: BWC draft policy, page 5, Section IV, Recording Requirements and Restrictions, subsection A, Mandatory BWC Recording

[3]: BWC draft policy, page 7, Section IV, Recording Requirements and Restrictions, subsection C, Prohibited BWC Recording, number 2c

[4]: BWC draft policy, page 5, Section IV, Recording Requirements and Restrictions, subsection A, Mandatory BWC Recording, numbers 1 - 15

[5]: BWC draft policy, page 9, Section IV, Recording Requirements and Restrictions, subsection E, Special Circumstances, number 4

[6]: Rochester Police Department General Order 630, "Special Weapons And Tactics (SWAT) Team," page 1188, from the Rochester Police Department General Order Manual

[7]: Rochester Police Department General Order 630, "Special Weapons And Tactics (SWAT) Team," page 1193, section E, from the Rochester Police Department General Order Manual

[8]: BWC draft policy, page 9, Section IV, Recording Requirements and Restrictions, subsection E, Special Circumstances, number 5

[9]: Rochester Police Department General Order 605, "Mobile Field Force," page 1147, from the Rochester Police Department General Order Manual

[10]: BWC draft policy, page 10, Section V, Employee Access to BWC Recordings, subsection A, Employees may review and use BWC recordings only for official RPD duties, number 1

[11]: BWC draft policy, page 11, Section V, Employee Access to BWC Recordings, subsection A, Employees may review and use BWC recordings only for official RPD duties, number 1 and attached note

[12]: BWC draft policy, page 18, Section XII, Disclosure of BWC Recordings in Legal Proceedings, subsection A, Criminal Cases Prosecuted by the Monroe County District Attorney's Office (MCDA), numbers 1 - 4

[13]: BWC draft policy, pages 18 - 19, Section XII, Disclosure of BWC Recordings in Legal Proceedings, subsection C, Defense Subpoenas or Demands in Criminal Cases, numbers 1 - 6

[14]: BWC draft policy, page 5, Section IV, Recording Requirements and Restrictions, subsection A, Mandatory BWC Recording

[15]: BWC draft policy, page 28, Appendix C, RPD BWC User Guide, bullet point 10, Tag the Recording – In accordance with training.

[16]: BWC draft policy, page 20, Section XIII, Freedom of Information Law (FOIL) Requests, subsection B, number 1

[17]: BWC draft policy, page 20, Section XIII, Freedom of Information Law (FOIL) Requests, subsection D, numbers 1 - 7

Related: WXXI Connections with Evan Dawson: RPD Body Worn Camera Project | Rochester Police Department General Orders Manual (March 2016) | What does the term “grenadier” mean to you? | NYS is a no SWAT zone! Reject SWAT conferences & police militarization | Police reform group makes policy recs to city for body cameras | Coalition praises council on body cameras; demands a voice in policy decisions

A "grenadier" at the 2013 Puerto Rican Festival, Rochester, NY

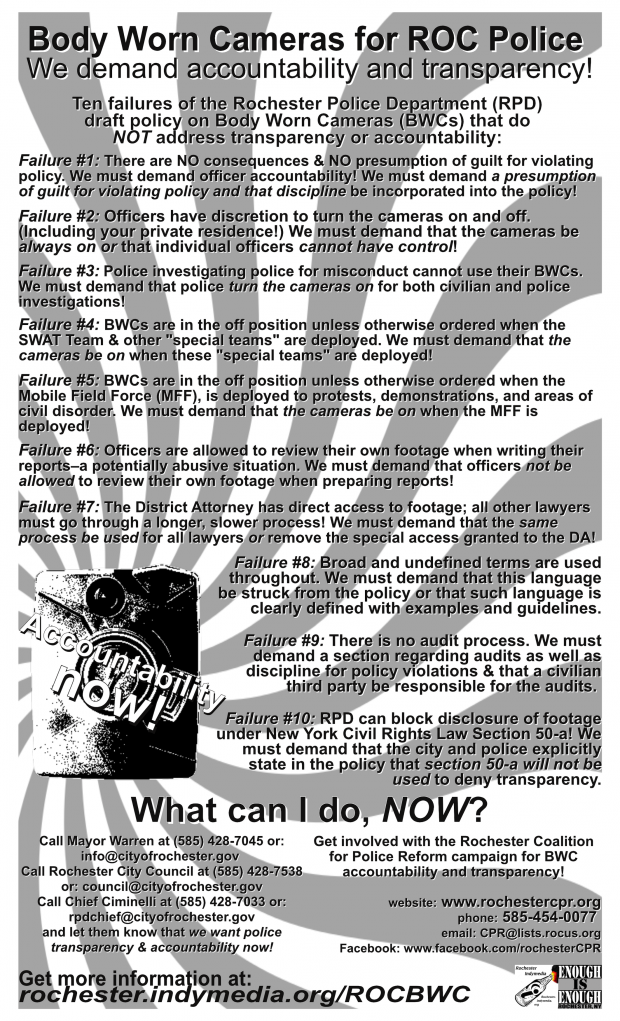

BWC Failure Flyer