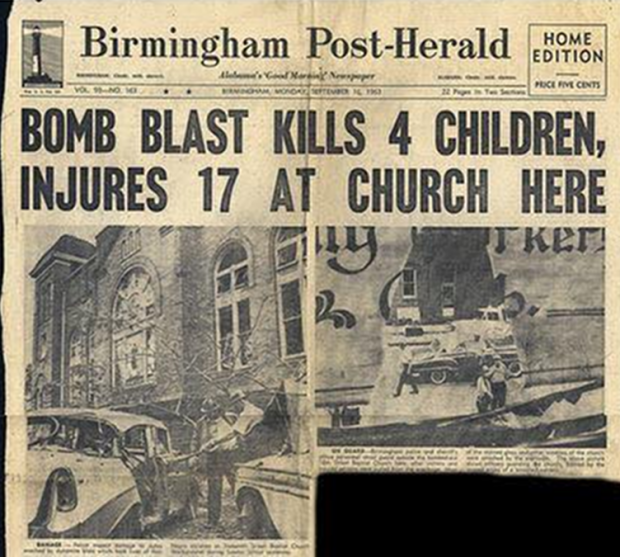

52 years ago today a Black church was bombed and four little girls were killed

Primary tabs

On this day 52 years ago--a Sunday--September 15, 1963, the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama was bombed by four members of the Ku Klux Klan killing four little girls. The four Black children were Addie Mae Collins (age 14), Carol Denise McNair (age 11), Carole Robertson (age 14), and Cynthia Wesley (age 14).

The four white-supremacist terrorists (Thomas Edwin Blanton, Jr.; Herman Frank Cash; Robert Edward Chambliss; and Bobby Frank Cherry) were not prosecuted until 1977--one of who, according to Wikipedia, died in 1994 before he could be charged.

The day after the bombing, Angela Y. Davis read about it in the paper while she was in Europe getting her education. Below are her thoughts on what happened the day after the bombing as related in her Autobiography. The passage is from pages 128-131.

"September 16, 1963

"After class I asked there three or four students with whom I was walking to wait a moment while I bought a Herald Tribune. My attention divided between walking and listening to the conversation, just skimming the paper, I saw a headline about four girls and a church bombing. At first I was only vaguely aware of the words. Then it hit me! It came crashing down all around me. Birmingham. 16th Street Baptist Church. The names. I closed my eyes, squeezing my lids into wrinkles as if I could squeeze what I had just read out of my head. When I opened my eyes again, the words were still there, the names traced our in stark black print.

"'Carole,' I said. 'Cynthia. They killed them.'

"My companions were looking at me with a puzzled expression. Unable to say anything more, I pointed to the article and gave the newspaper to an outstretched hand.

"'I know them. They're my friends. . .' I was spluttering.

"As if she were repeating lines she had rehearsed, one of them said, 'I'm sorry. It's too bad that it had to happen.'

"Before she spoke I was on the verge of pouring out all the feelings that had been unleashed in me by the news of the bomb which had ripped through four young Black girls in my hometown. But the faces around me were closed. They knew nothing of racism and the only way they knew how to relate to me at that moment was to console me as if friends had just been killed in a plane crash.

"'What a terrible thing,' one of them said. I left them abruptly, unwilling to let them have anything to do with my grief.

"I kept staring at the names. Carole Robertson. Cynthia Wesley. Addie Mae Collins. Denise McNair. Carole--her family and my family had been close as long as I could remember. Carole, plump, with long wavy braids and a sweet face, was one of my sister's best friends. She and Fania were about the same age. They had played together, gone to dancing lessons together, attended little parties together. Carole's older sister and I had constantly had to deal with our younger sisters' wanting to tag along when we went places with our friends. Mother told me later that when Mrs. Robertson heard that the church had been bombed, she called to ask Mother to drive her downtown to pick up Carole. She didn't find out, Mother said, until they saw pieces of her body scattered about.

"The Wesleys had been among the Black people to move to the west side of Center Street. Our house was on Eleventh Court; theirs was on Eleventh Avenue. From our back door to their back door was just a few hundred feet across a gravel driveway that cut the block in two. The Wesleys were childless, and from the way they played with us it was obvious that they loved children. I remembered when Cynthia, just a few years old, first came to stay with the Wesleys. Cynthia's own family was large and suffered from the worst poverty. Cynthia would stay with the Wesleys for a while, then return to her family--this went on until the stretches of time she spent with the Wesleys grew longer and her stays at home grew shorter. Finally, with the approval of her family, the Wesleys officially adopted her. She was always immaculate, her face had a freshly scrubbed look about it, her dresses were always starched and her little pocketbook always matched her newly shined shoes. When my sister Fania came into the house looking grubby and bedraggled, my mother would often ask her why she couldn't keep herself clean like Cynthia. She was a very thin, very sensitive child and even though I was five years older, I thought she had an understanding of things that was far more mature than mine. When she came to the house, she seemed to enjoy talking to my mother more than playing with Fania.

"Denise McNair. Addie Mae Collins. My mother had taught Denise when she was in first grade and Addie Mae, although we didn't know her personally, could have been any Black child in my neighborhood.

"When the lives of these four girls were so ruthlessly wiped out, my pain was deeply personal. But when the initial hurt and rage had subsided enough for me to think a little more clearly, I was struck by the objective significance of these murders.

"This act was not an aberration. It was not something sparked by a few extremists gone mad. On the contrary, it was logical, inevitable. The people who planted the bomb in the girls' restroom in the basement of 16th Street Baptist Church were not pathological, but rather the normal products of their surroundings. And it was this spectacular, violent event, the savage dismembering of four little girls, which had burst out of the daily, sometimes even dull, routine of racist oppression.

"No matter how much I talked, the people around me were simply incapable of grasping it. They could not understand why the whole society was guilty of this murder--why their beloved Kennedy was also to blame, why the whole ruling stratum in their country, by being guilty of racism, was also guilty of this murder.

"Those bomb-wielding racists, of course, did not plan specifically the deaths of Carole, Cynthia, Addie Mae, and Denise. They may not have even consciously taken into account the possibility of someone's death. They wanted to terrorize Birmingham's Black population, which had been stirred out of its slumber into active involvement in the struggle for Black liberation. They wanted to destroy this movement before it became too deeply rooted in our minds and our lives. This is what they wanted to do and they didn't care if someone happened to get killed. It didn't matter to them one way or the other. The broken bodies of Cynthia, Carole, Addie Mae, and Denise were incidental to the main thing--which was precisely why the murders were even more abominable than if they had been deliberately planned."